Refastening a Wooden Hull - Season 4, Episode 1 Now Available!

How to Build a Wooden Mast

A tapered, oval new york 32 spar from the original plans.

ISLA, New York 32 No.10 (of a total of 20), was thoroughly rebuilt last year by Buzzards Bay Yacht Services of Mattapoisett, Massachusetts. The job included a new mast, whose construction is detailed on the following pages.

W hen my company was hired to restore New York 32 No. 10, ISLA, in 2008, the boat had been out of service for over 25 years. The 20-boat New York 32 fleet was designed by Sparkman & Stephens in 1935 and built over the winter of 1935–36 by Henry B. Nevins of City Island, New York. When we found her, ISLA was a virtual time capsule, with an intact original interior and a complete set of original hardware. But the hull and deck were tired, to say the least, and the spars were beyond repair. So, included in the work list were a new mast and boom.

The New York 32 carries a hollow, oval mast measuring 63′ 5″. The owners were committed to maintaining ISLA’s originality, so we acquired the original spar drawings from the S&S plan collection at Mystic Seaport. These included ample detail: spreaders, tangs, boom, and masthead, along with the overall mast plan. The following steps describe how we turned those drawings into a new mast for ISLA.

Ordering and Preparing Lumber ISLA’s mast is built of Sitka spruce, which has long been prized by sparmakers for its long, clear lengths, light weight, and impressive strength for that weight. From the plans we developed a lumber list for the mast, boom, and spreaders. While it is still possible to acquire excellent-quality Sitka spruce, it takes some searching and a keen eye for defects. We required at least 12/4 stock to fashion the forward and after staves.

For spars, it’s imperative that the wood be dry (below 15 percent moisture content) and free of defects. The grain must be vertical. Our first attempt to procure lumber for this mast resulted in us receiving a batch of 12/4 Sitka spruce that was case-hardened. It was dry to both the touch and to the moisture meter, but once milled and its center exposed, its moisture content went off the scale. When we tried to rip it on the tablesaw, it pinched the saw’s blade and stopped the saw. We replaced that batch of wood with properly dried material, and learned a lesson in the process.

We ran the rough-sawn boards we had purchased through the thickness planer to take “fur” off of each one, allowing for a better inspection of the surface of the wood. When doing so, we kept in mind the minimum thickness of the staves, so we wouldn’t carelessly plane off too much. With this done, we examined each board, measuring its usable portion, marking visible defects, and labeling each piece for its intended location in the mast. A board with tight grain is slightly denser and thus heavier than one with wider ring spacing; we strived to locate these heavier pieces toward the bottom of the spar. If another board had slight grain runout, we’d consider using it in the mast’s heel where it is under less stress and is backed by solid blocking. It’s also important to keep in mind the locations of the scarfs when selecting the lengths of stock that will compose each stave, for the scarfs must be staggered.

Utilizing the Drawing

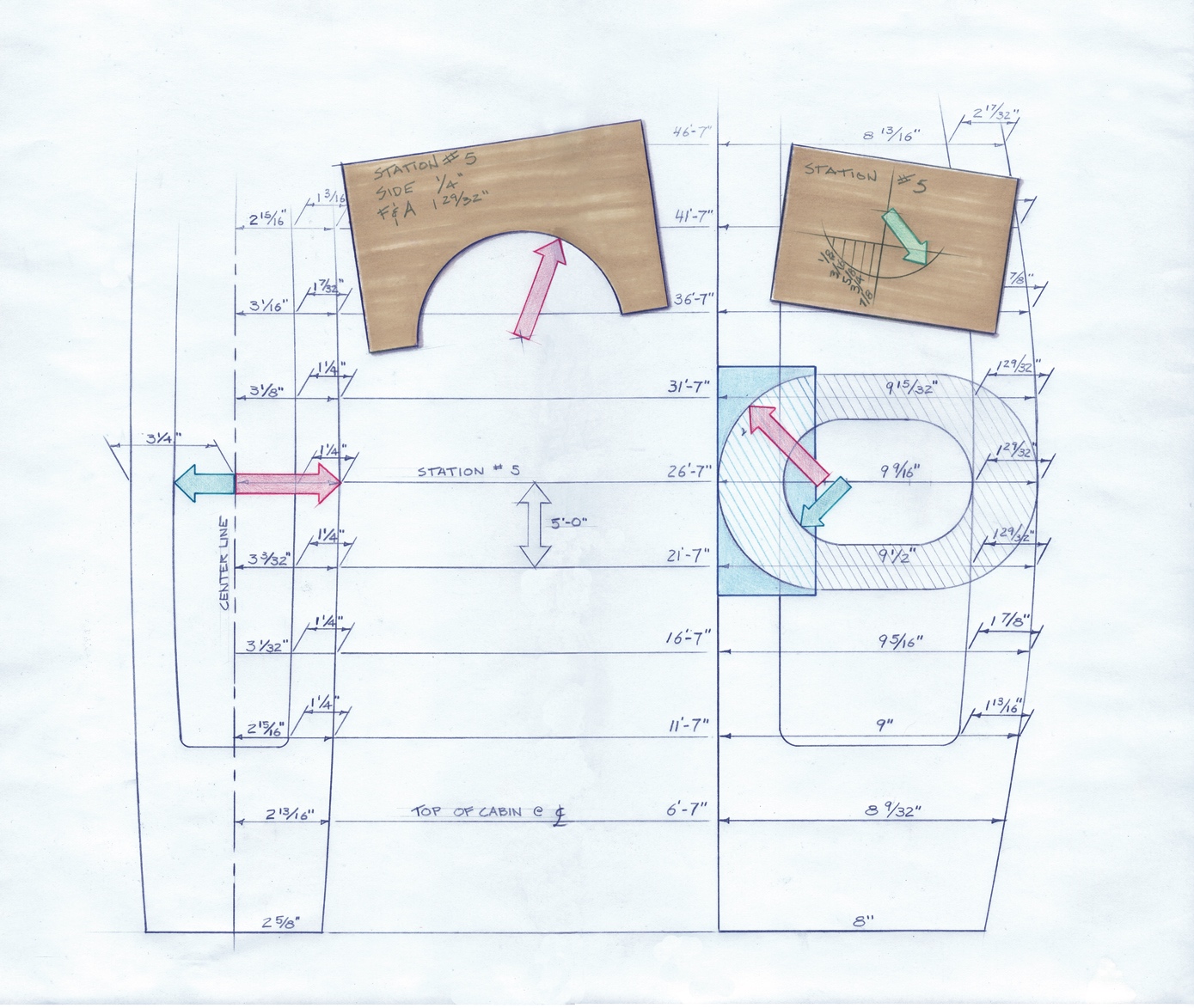

The drawing shown here is an illustration of the original Sparkman & Stephens mast plan for the New York 32, whose vertical scale was compressed in order to fit the mast’s dimensions onto a single sheet of paper. From the drawing we created a table of offsets for the mast. To do this we drew a series of stations, 5′ apart, perpendicular to the mast’s centerline. We did this for both the side and forward views of the mast.

The drawing shown here is an illustration of the original Sparkman & Stephens mast plan for the New York 32

For the forward and after staves, we recorded the overall thickness of the stave (that is, its thickness before hollowing) and its half width. For the side staves, we recorded the thickness and width at each station. We converted the mast plan drawing from 32nds of an inch to decimal units, which I find best when working to close tolerances using digital calipers. We then made up 10″ × 10″ lauan templates on which to draw the sectional shape of the mast at each station. Since the forward and after profiles are arcs of a circle, we transferred these shapes from the drawing to the lauan with the aid of a compass. After each shape was transferred we cut out these lauan templates with a bandsaw. On each template, we also recorded the sidewall thickness, forward and after wall thicknesses, and distance from the heel of the mast. Building this New York 32 mast as was done originally requires hollowing out the thick forward and after staves in order to lighten their weight. So, once again using the mast plan, we made templates for the mast’s inside shape at each section.

The Spar Bench

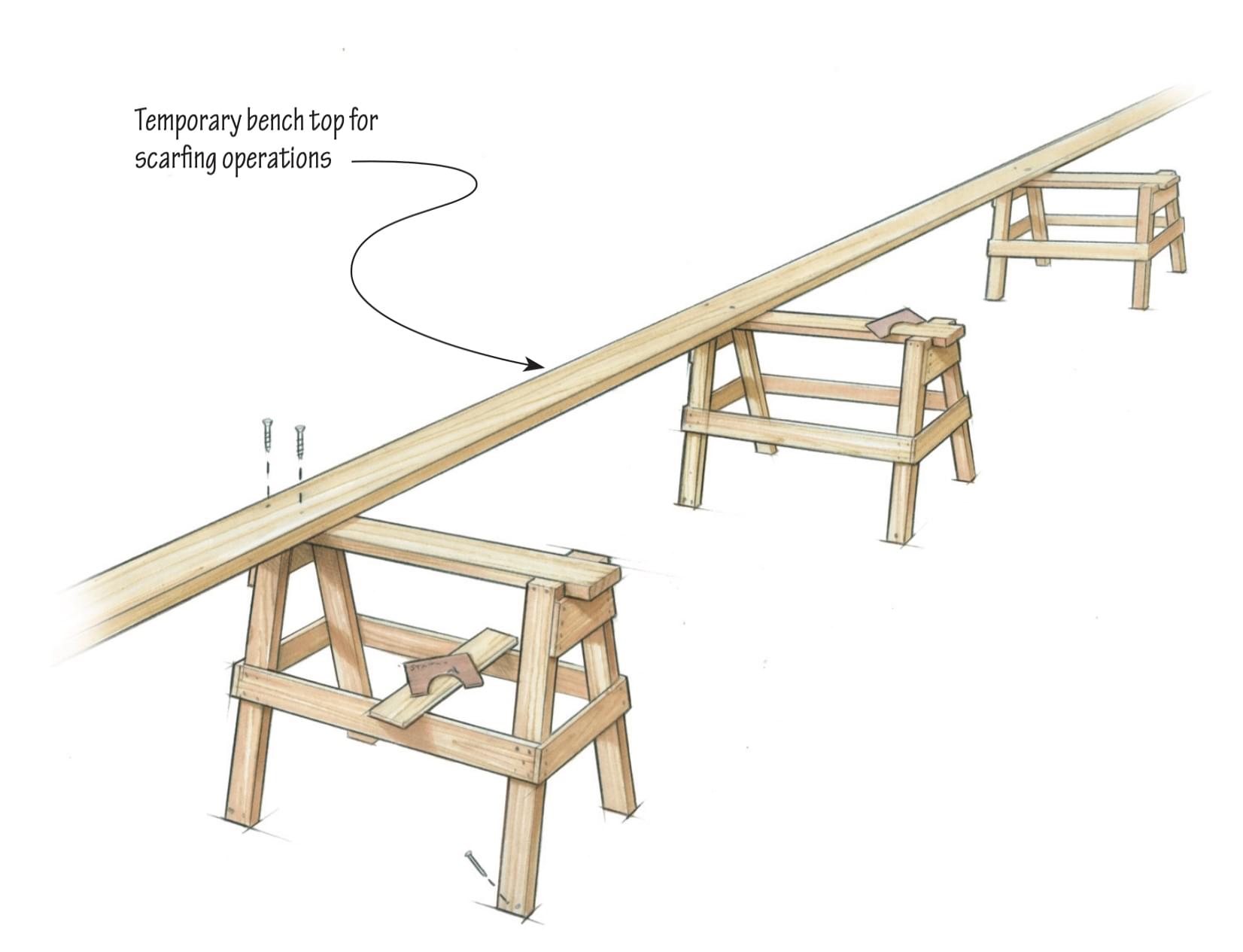

The first step in building the mast is to construct a spar bench. We wanted a sturdy bench that was straight and set at a good working height. Typically, a spar bench comprises a series of sturdy sawhorses spaced 5′ apart and fastened securely to the shop floor. Identical wooden sawhorses work well for this; once they were secured to the floor, a mason’s string was run to assure that the tops were all in the same plane; the tops were then shimmed as needed to achieve this. The 2 × 10 plank seen here being screwed to the sawhorses is to support the staves during the scarfing operation, and will later be removed.

Gluing Up Full-Length Staves

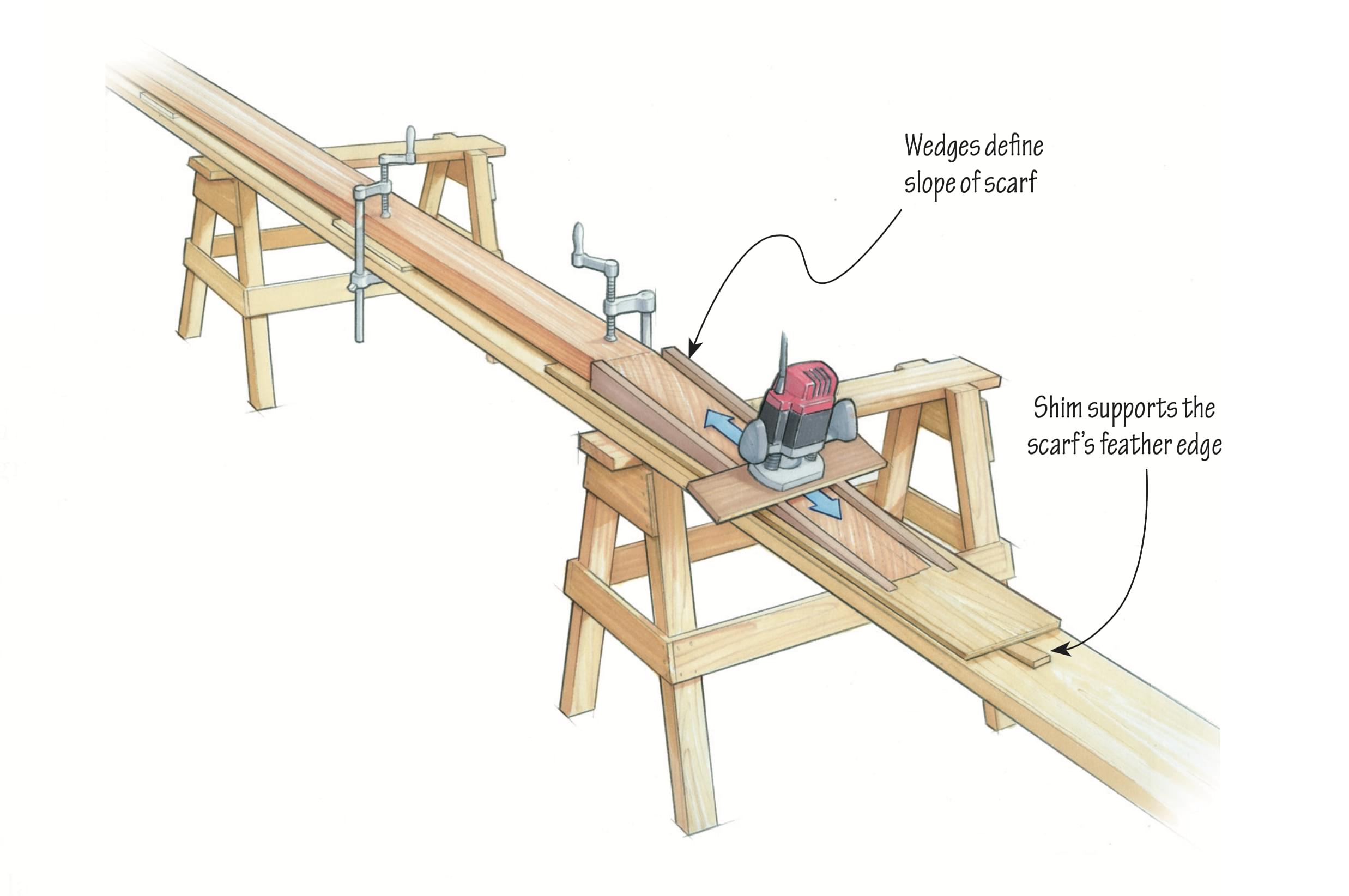

On our nice, solid bench, we laid out the wood for each of the mast’s four staves end-to-end and developed a final scarf plan. We planed the stock to the maximum designed thickness for the forward and after staves (2.875″) and for the side staves (1.25″). Then we scarfed the stock together to create the full-length staves. Careful layout and labeling were required for this step. We examined the stock and put the most visually pleasing sides facing out, and we spread out the scarf locations to avoid clustering them. Scarfs were cut to a slope of 12 to 1, with their lines drawn onto the edges of each piece. They were rough-cut on the bandsaw, and then finished with a jig and a router. With the scarfs cut, we assembled the pieces dry and ran a string down each of their centerlines to confirm that each of the four full-length staves, once glued, would be straight.

When we were certain that the staves would be straight and true, we screwed blocks to the spar bench to chock them in place. The individual pieces could then be removed from the bench, turned over for gluing, and placed back in their precise positions. The final step in preparing the scarf for epoxy glue was to rough up the surface of the glue joint. Eighty-grit sandpaper backed by a long block works well for this, as does the technique we used: a Japanese pull saw drawn across the grain so its teeth combed the surface. (This process is for epoxy gluing only; resorcinol and other glues rely on smooth mating surfaces.)

Once the surface was roughed up, we vacuumed both faces of the joint and then wiped them with a clean rag and denatured alcohol until the rags came up clean. We then wet out both gluing surfaces with straight epoxy and allowed that to stand for several minutes while it penetrated the wood. Dry spots were wetted a second time. We then applied epoxy thickened with colloidal silica to one face of the joint. Using large bar clamps and modest pressure, we clamped the joints, making sure we had a nice, even glue squeeze-out.

Tapering the Staves

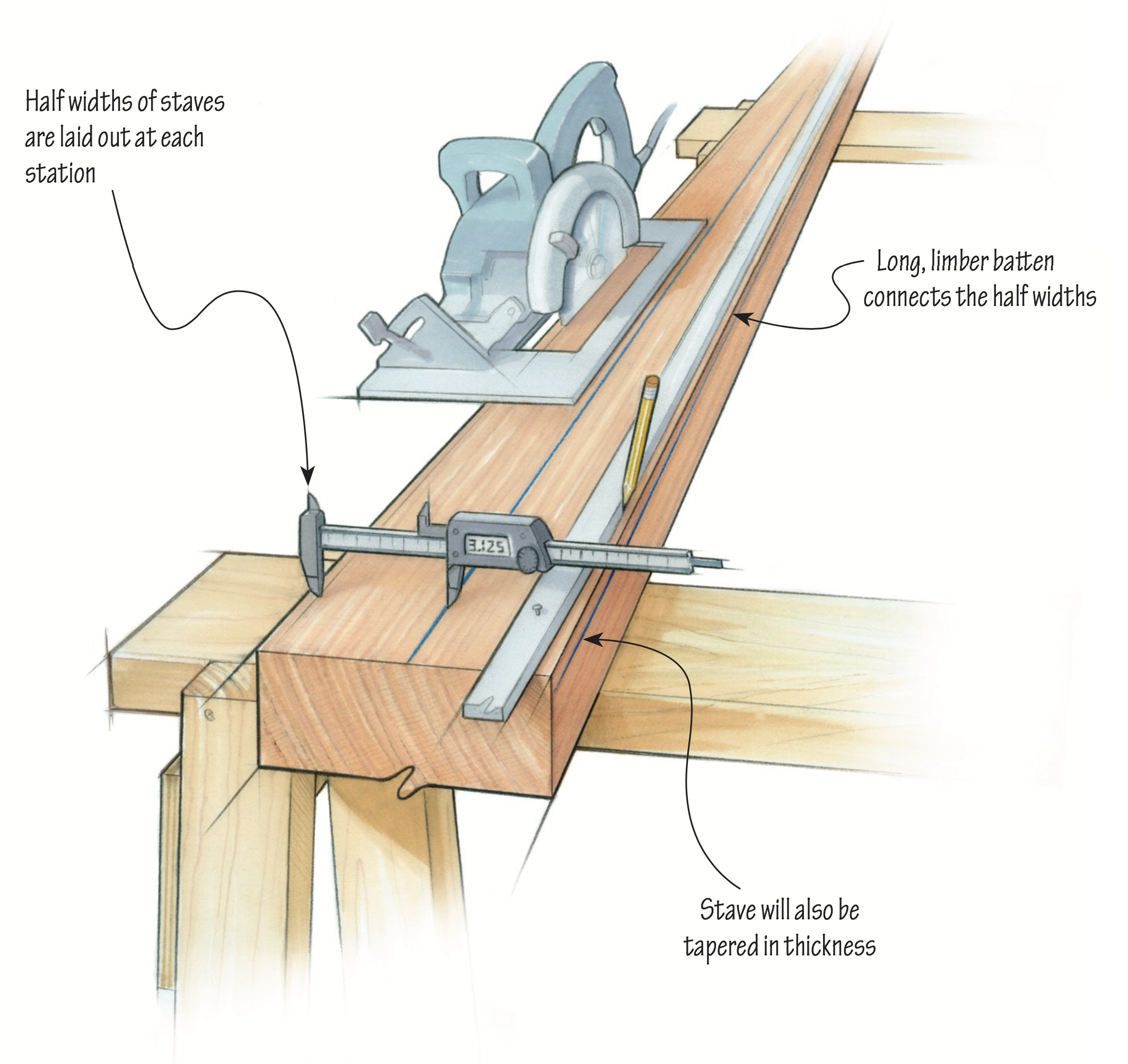

Once the staves were glued full-length, we selected the aft stave, blocked it straight on the spar bench, and snapped a centerline. Then, using the information from the lauan templates and the offset table, the points representing the stave’s profile were laid out and connected with a long, limber batten. One of the side staves was marked similarly.

We rough-cut the profiles with a worm-drive circular saw being careful to leave the lines intact. We then cut closer with a power plane, and then shaved precisely to the lines with an appropriate hand plane, making sure that the edges stayed perfectly square. With one stave of each profile now complete, we used each as a template for its mirroring stave, making the final cuts with a router and bearing bit to complete the second pair of staves.

To minimize weight aloft, the wall thickness diminishes as we progress up the mast. Once again we turned to the lauan templates on which we’d recorded the wall thickness at each station. Using digital calipers, we recorded on both edges of each stave the wall thickness at each station and connected the dots with our long batten.

This line, yet to be cut, is shown in the drawing. The stock was removed from the outside faces of the staves, the bulk of it with a power plane. The final cleanup was completed with a bench plane.

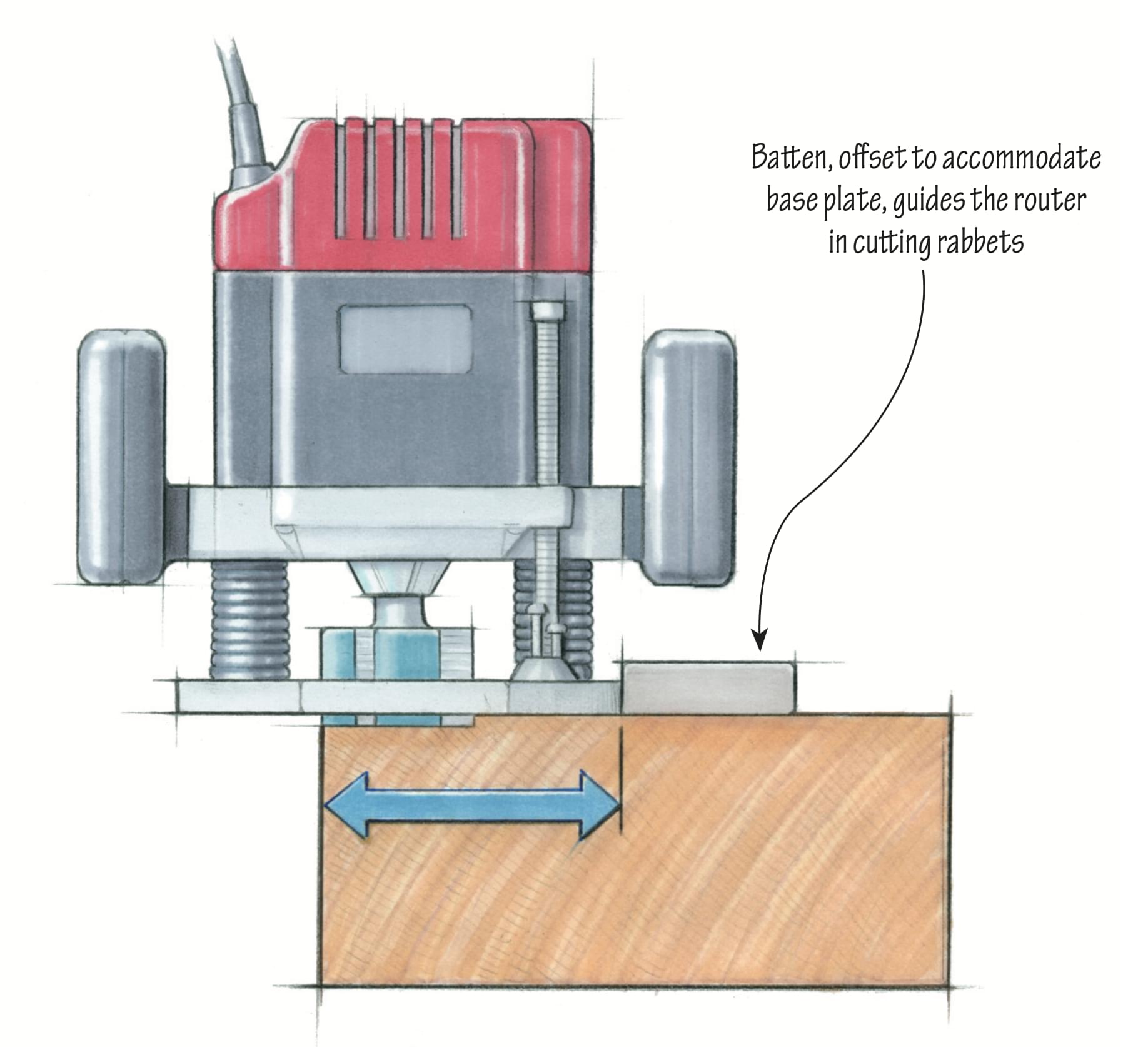

Rabbeting the Forward and After Staves

Hollowing the Forward and After Stave

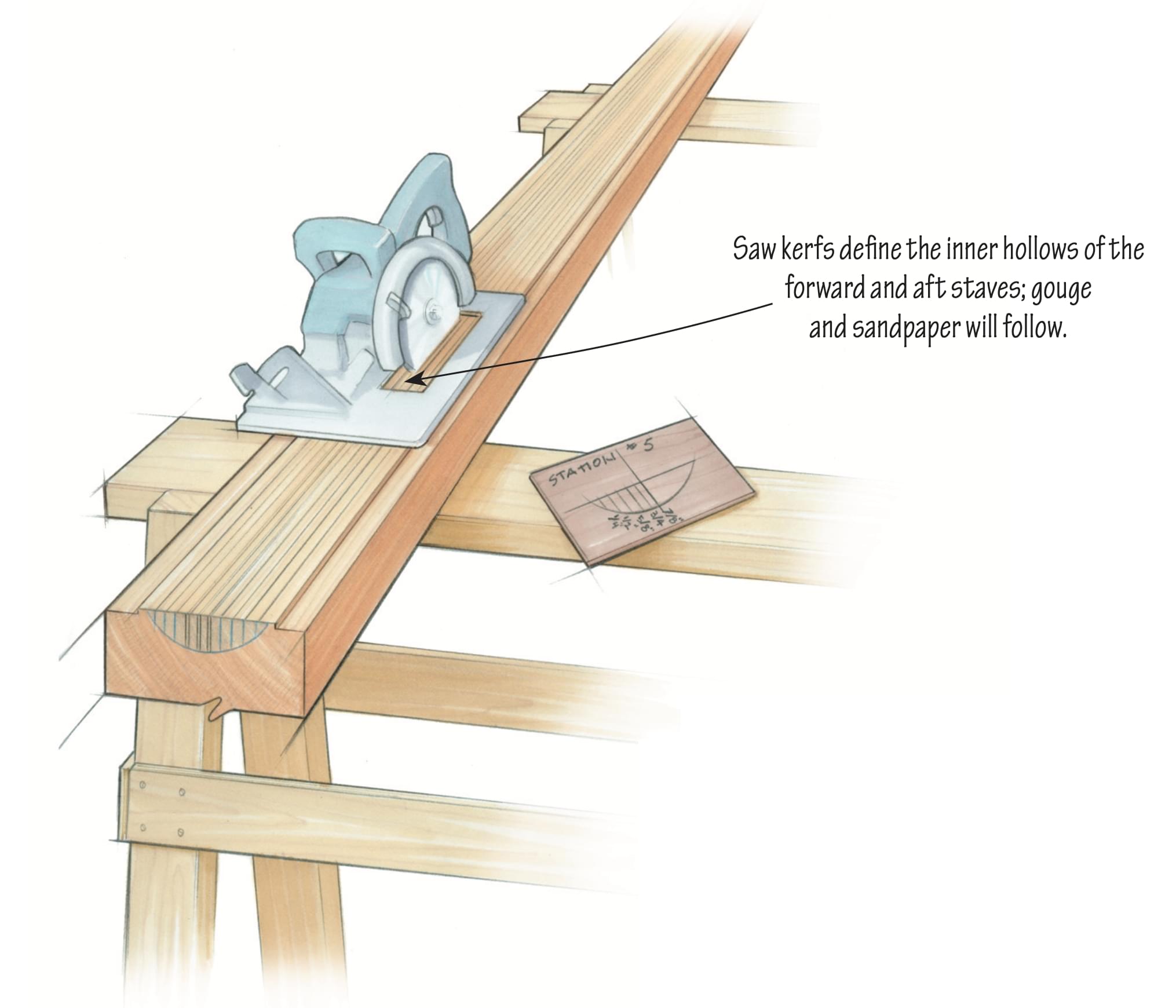

The final step before gluing the staves together was to hollow out the forward and after staves. On the lauan templates we referred to the inside profile shapes we had recorded from the mast drawing. Dividing the inside profile into 1⁄4″ sections, we measured and recorded the depth at each section. We did this at each station. The inside face of the stave was thus lined off in 1⁄4″ increments.

Then, using a circular saw set at the depth indicated by the lauan template, we cut kerfs in the inside face of the stave. With each pass of the saw, we reduced the depth of the cut as we moved toward the masthead and farther from the center of the stave. With the kerfs completed, we used a gouge to scoop out the waste. We arrived at the final shape by using a backing-out plane followed by 80-grit sandpaper on a round sanding block.

With the staves cut to their profiles and tapered in thickness, and the forward and after staves rabbeted and hollowed, we double checked that the spar bench was still straight. The next step was to lay the after stave on the bench, sail-track side down, and hold it straight with blocks screwed to the bench so the spar could not move. We then did a final dry-fit of the three remaining staves to make sure all joints were tight.

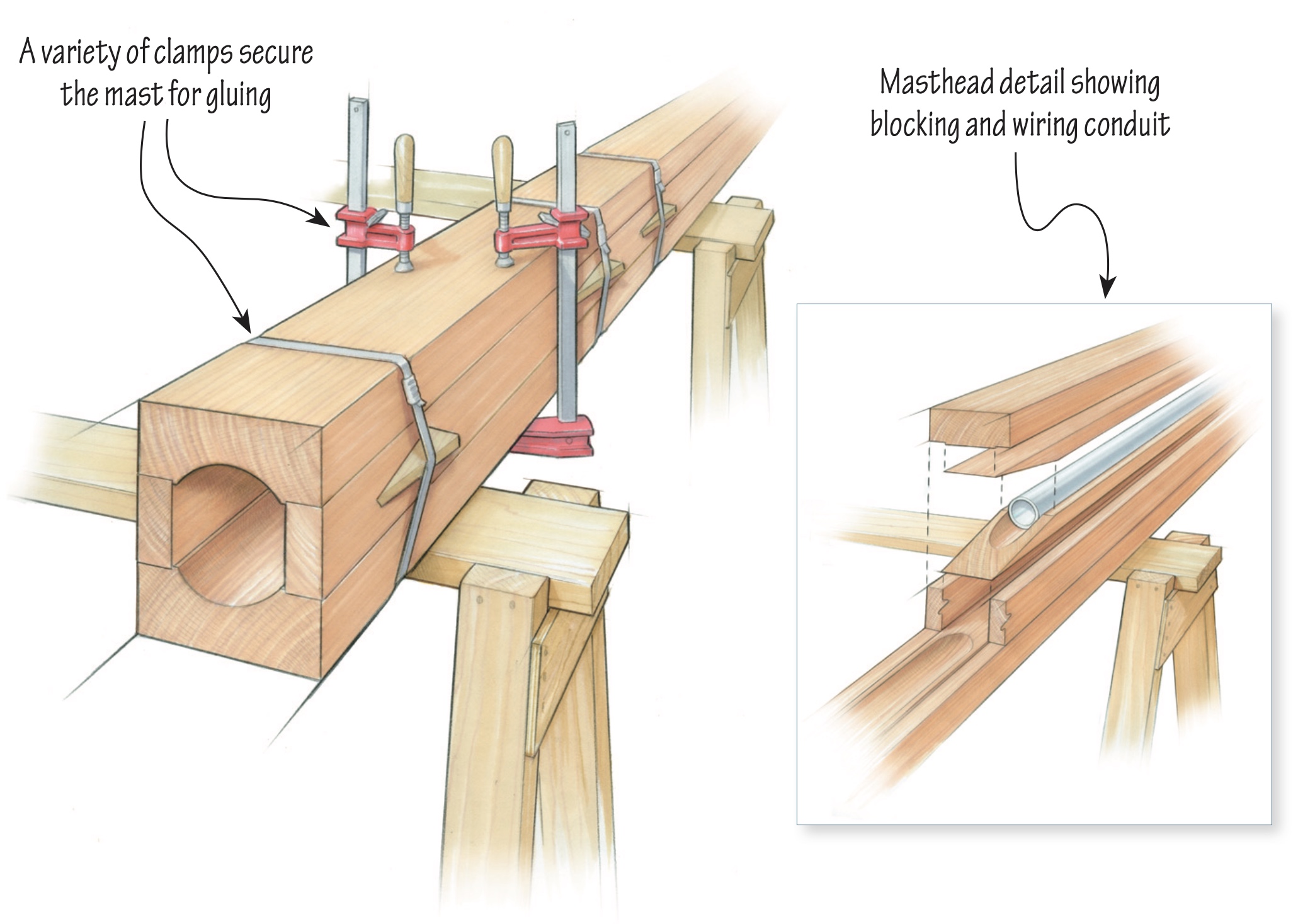

When satisfied with the bench and the joints, we began mixing glue. A large spar such as this takes about four people to glue up; any fewer, and panic would certainly ensue. The glue-up seems to work best as a two-step process. The first step was to glue the side staves to the after stave, using the forward stave as a dry-fitted guide to ensure that the side staves remained parallel. We clamped the spar in 1′ increments, checking that it remained square along its entire length. Using the two-step process allows ample time to fit and install the solid blocking at the head and heel of the mast. The drawing calls for blocking in the bottom 11′ of the spar and in the top 2′ 6″.

The blocking is solid until about the final foot, where it tapers to a feather edge on either side of the spar, forming a swallow-tail shape to avoid a hard spot. This heel blocking has a drain hole, in case of water intrusion. There is no blocking at the spreaders; instead, the spreaders have an external bracket and blocking system that transfers the load evenly to the spar.

We coated all interior surfaces with epoxy. At this stage, we also ran all of the wires inside the mast, securing them with large cable clamps. (Conduit fastened securely along the interior of the spar—and through the blocking—works well for this, too.) When everything was satisfactory inside the mast, the forward stave was glued to the side staves to cap the assembly. Several varieties of clamps can be used when gluing up a spar: spar clamps, bar clamps, C-clamps, or a banding tool. We used a combination of clamps and a banding tool supplemented with wedges to further tension the plastic band.

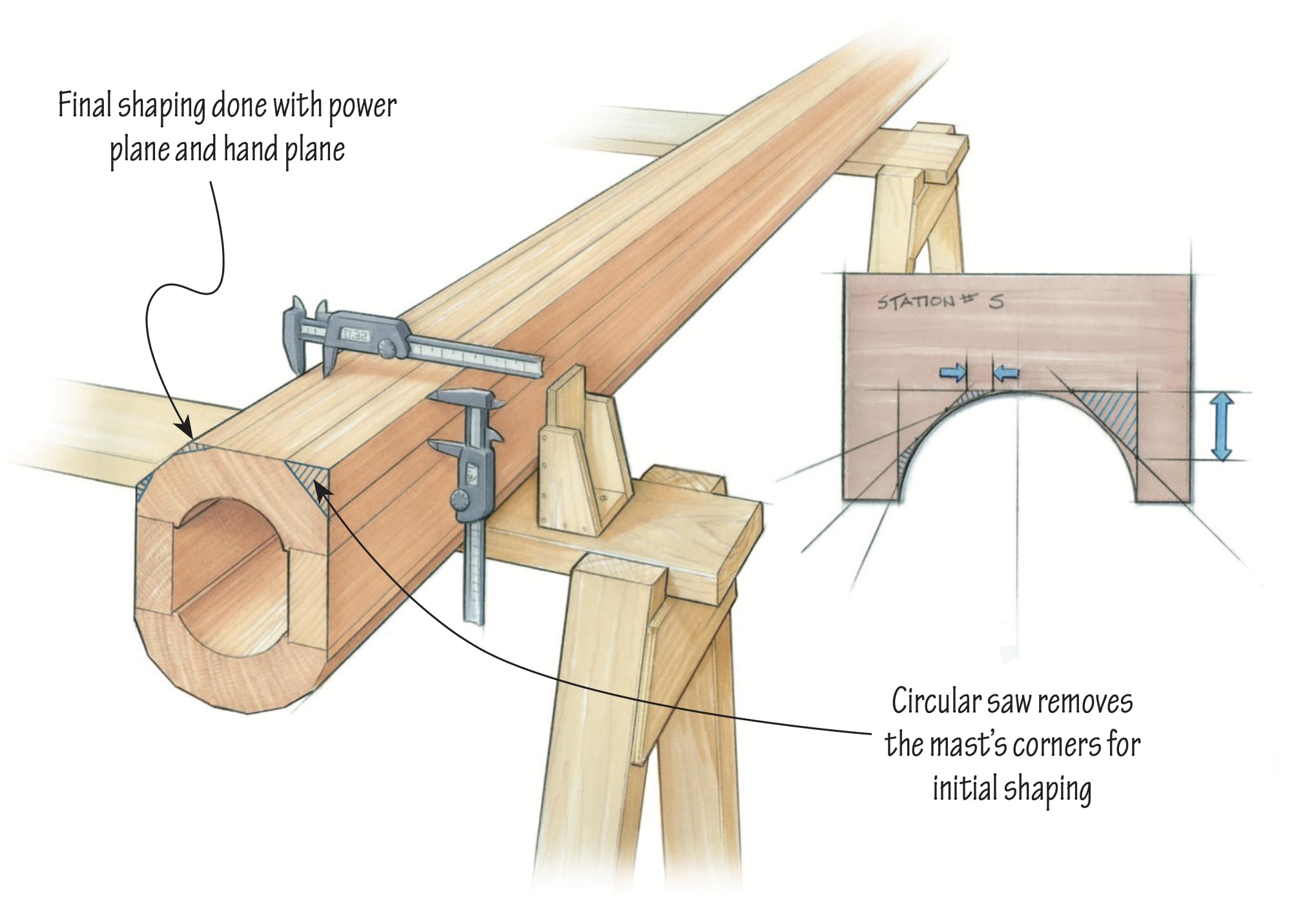

With the glue cured and the clamps off, it was time to begin the shaping process. The first step was to plane off the excess glue. With that done, we again turned to our handy lauan templates and began the process of eight-siding the spar. Using the exterior cross-section drawn on each template, we found where a 45-degree line would be tangent to the mast’s outside surface at each station. We transferred these points to the spar, and with the long batten connected them with fair lines.

We then set our circular saw to 45 degrees and made a cut, just leaving the line. Repeating this on all four sides of the mast, and then fairing up the saw cuts with a power plane followed by a hand plane, yielded an eight-sided spar. We then lined the spar off again to 16 sides, but this time we omitted the circular saw and removed the waste with only a power plane. When we had the spar 16-sided, we finished the rounding and fairing with hand planes and a custom-built concave fairing board. Once again our lauan templates came into play, as we used them to confirm the correct shape at each station. Two other details that had to be considered at this stage were the shape of the heel of the spar, and the masthead detail.

With the mast now shaped and sanded, we broke out the varnish and applied 10 coats before installing the track and hardware. We were fortunate to have all of the original tangs and other fittings for this spar, because fabricating them would have required quite a bit more work. With the spar varnished the hardware was installed, carefully bedded in soft compound. We were very careful in fastening into the Sitka spruce, as it is quite soft. We chose machine screws rather than wood screws for mounting the winches and the boom gooseneck track—after testing these fastenings on offcuts to find the best pilot-hole diameters.

This article was originally published in WoodenBoat No. 214, May/June 2010.

Related Articles

Laminating knees and frames for small craft, virginia park, a sliding tool tray, marine plywood – a consumers guide, related videos, interior joinery, scarf joints, refastening a wooden hull, making homemade boatbuilding tools, related book chapters, laying down, building the house, deck framing, laying the deck, subscribe for full access.

Flipbooks are available to paid subscribers only. Subscribe now or log in for access.

Shaw and Tenney Home

- Traditional Oars

- Sculls, Adirondack, Specialty and Large Oars

- Marine Hardware, Oarlocks, Leathers and Accessories

- Traditional Canoe Paddles

- Kayak Paddles

- SUP Paddles

- Artisan Canoe Paddles

- Paddling Accessories

Wooden Masts and Spars

- The Shaw & Tenney Whitehall

- Camp and Home

- Pack Baskets and Bags

- Miniature Paddles and Oars

- Custom Engraving

Shopping Cart

Shaw and tenney mobile nav.

- Gear & Apparel

- Awards & Engraving

Product Header Image

Our wooden masts and spars are made with the same uncompromising quality and attention to detail as our oars and paddles. We have made hundreds of masts and spars for boats as small as nutshell prams, for many Herreshoff designs, and numerous larger boats like Concordia yawls. Due to our shop size, 50 feet is our maximum length.

We offer solid and hollow masts in a variety of cross-sections. We typically require the original naval architects drawings or your old mast, but can assist you in dimensioning the mast if the aforementioned items are unavailable to you.

Most of our masts and spars are constructed from select Eastern red spruce. Ideal for mast making, it has the highest strength to weight ratio of all North American softwoods. We also offer Sitka spruce and Douglas fir as options.

Please call us to discuss your mast and spar needs.

Unfortunately, because of its length, this product cannot be shipped through our Online Store. Please call 800-240-4867 to place your order.

Select Your Wood

How to Size Your Oars

To determine the correct length oar for your boat measure the distance between the port and starboard oar sockets. Then apply the Shaw and Tenney oar length formula to determine the oar length that will provide the correct 7:18 leverage ratio. This length will provide an oar where 7/25 the length is inboard of the oarlocks and 18/25 of the oar is outboard of the oarlocks. It is the ideal ratio to row almost all boats. Sized correctly, when rowing your hands will be 1 to 3 inches apart and you will be pulling directly towards your abdomen. If you are popping out of your oarlocks when rowing your oars are far too short. If you prefer an overlapping grip, add 6” to the calculated oar length. If you have more than one rowing station in your boat, measure both. Typically they will require two different length oars which is fine if you’re going to be rowing tandem and need two sets. Otherwise you’ll need to compromise the correct length to work properly in both stations. If you are rowing more than 75% in one station size the oar to that length. As always feel free to call us and were happy to help you select the correct oar length and blade style for your boat.

The Original Shaw & Tenney Oar Length Formula

To help our customers size their oars correctly, we’ve been using the same formula since 1858: Measure the distance between the center of the port and starboard oar sockets, which hold the oar locks on each gunnel. This is called the “span” between the oarlocks. Divide the span by 2, and then add 2 to this number. The result is called the “inboard loom length” of the oar. Multiply the loom length by 25, and then divide that number by 7. The result is the proper oar length in inches. Round up or down to the closest 6” increment.

How to Size Your Paddle

For traditional wooden paddles the ideal length for the Stern paddler is the bridge of your nose or 6 inches less than your height. For the bow paddler the paddle reaching the cleft of your chin or 9 inches less than your height is correct.

For our Racine paddle if you are over 5’6” tall select the 63-1/2” length and the shorter paddle if you are under5’-6”tall.

When paddling solo we typically recommend a bow length paddle. For Canadian style solo most paddlers prefer an even shorter paddle.

For paddling canoes when standing (yes our mother let us do this) a 69 inch or 72 inch paddle is usually about right.

Additional Views

You Might Also Be Interested In:

Shaw and Tenney

Toll Free: 800-240-4867 207-866-4867 20 Water Street, PO Box 213, Orono, Maine 04473

Shop Shaw & Tenney

More information.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Stay In Touch with Shaw & Tenney

© 2021 Shaw & Tenney, Inc.

Have a question or need some help?

Call us at 800-240-4867 or click here to send us an email . Thanks!

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

In Search of the Snag-free Clew

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Breaking Point: What Can Go Wrong With Your Yanmar?

Mildew-resistant Caulks for Boats

Can We Trust Plastic Boat Parts?

Repairing Molded Plastics

Mailport: Marine plywood, fuel additives, through bolt options, winch handle holders

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Resurrecting Slippery Boat Shoes

Shoe Goo’s Gift to Sailors

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

The Ultimate Guide to Caring for Clear Plastic

- Inside Practical Sailor

Pondering Options for Varnishing a Mast

As a mast and rigging overhaul creeps toward the top of the refit list on my 1971 Yankee 30, Opal , I’m thankful I’m no longer the custodian of wooden spars, as I was on my old Atkin ketch, Tosca . It’s not that a wooden spar is any less capable than an aluminum one, and a well-kept wooden spar is far more lovely to look at, in my view. However, wooden spars have gone the way of the Walker taffrail log for a reason.

In the tropics at least, taking wood out of the equation offers some relief from the unending battle against the elements. In short, aluminum does not rot. The best weapon against mast rot is to truck the boat off to Sedona, AZ or some other arid place where each exhalation turns instantly into dust. Since the name of this publication suggests we are supposed to offer practical solutions for sailors, this clearly is not an option.

In the “ Exterior Wood Finish Update ” in the July 2021 issue of Practical Sailor, we revisit clear wood finishes, looking specifically at ease of application, gloss, color retention, and durability after two years. If you have questions about which varnish looks great after two years in the sun, that’s the place to look. Another important factor to consider is hardness—a feature that is particularly important for those areas that see a lot of foot traffic, abrasion, or impact from halyards or shackles. Masts, spars, tillers, and classic wood blocks and cleats probably see the most banging out of any wood component on the boat. As anyone who has decided to refinish their spars will tell you: there is no shortage of opinions on what product to use.

Last month’s report on reviving aluminum masts also revived one of the most common questions we get regarding marine varnish: What kind of finish is best for a wood mast? Even though aluminum has long since replaced Sitka spruce as the material of choice for a sailboat mast, there are plenty of wooden masts still in service. Many of the Taiwanese-built boats of the 70s and 80s had wooden masts, and of course, a wide range of U.S.-built classics still have their original wooden masts. And there are plenty of aluminum masts with spruce spreaders—my Yankee 30 among them.

Why Not Paint?

Clear-coating wood is more than an aesthetic preference. One of the main reasons a sailor would choose to clear-coat a wood component is to make any potential rot visible as soon as possible. Warding off fungus becomes particularly important in your spars, where any significant weakening could have disastrous consequences.

Although a high-quality paint will provide excellent protection to a wooden mast or boom, the paint can often hide cracks and seams where water is penetrating, creating a fertile ground for rot to take hold. Without frequent, careful inspections, these seemingly harmless dings and chips in your coating can open the door to more serious damage that can go unseen.

By comparison, when moisture penetrates a clear coating, the wood usually darkens, making any failures in the coating more obvious, allowing you to quickly head off more serious damage.

The most persuasive argument in favor of a painted mast is the ease of maintenance — but this, too, is based on some common misconceptions. Yes, it is generally easier to slap on another coat of alkyd enamel paint than it is to apply another varnish top-coat, but the time and effort advantage is not so significant once one adopts a clear-coat maintenance regimen. In both cases, re-coating generally means going aloft with a can and a brush, so the pace of application is already handicapped.

Depending on where you are cruising, both coatings will need a new top coat every three years at least. With today’s easy-flowing, quick-drying varnishes, you can refinish a spar with varnish at nearly the same pace as you can with paint.

If you are refinishing your spar “from scratch” (removing hardware, stripping down to bare wood, etc.), spray coating can further close the ease-of-application gap between paint and varnish. In the end, they are both coatings, and the prep work required of a quality finish is not much different. And when it comes time to recoat, varnish’s tendency to be less forgiving of application flaws works in its favor during annual inspections.

Sealing with Epoxy

Undoubtedly, when you begin any wood refinishing project—especially one involving a mast, spar or caprail — someone will tell you that they had great results sealing the wooden member with epoxy before recoating with varnish. While we do not doubt that the initial results from this application can be impressive, we are not big fans of sealing wood with epoxy. Here’s the gist of a previous PS Advisor that we wrote on this topic.

For those who have read our in-depth report on epoxy finishes “Stuck Like Glue” , it would seem that epoxy would be a logical choice for keeping moisture at bay and dealing with abrasion from halyards. But there’s more to this question than simply finding a material with good adhesion and a durable, abrasion-resistant bright finish.

Soft woods see a lot of moisture-induced surface movement, so coatings must be able to cope with the physical surface changes linked to dry, hot weather and the wet, cooler times of the year. That is why many people prefer relatively flexible spar varnishes for such applications. Although they’re less durable from an abrasion-resistance perspective than hard coatings like epoxy, they do give the wood that elegant amber look.

Epoxy resin is the vise-grip of all coating materials, but it has poor handling characteristics (flow, leveling, brushability) and no UV inhibitors. Mas Epoxies, however, are less viscous than most epoxies and tend to penetrate the substrates surface, making their flow out a little easier to control.

Using any epoxy as a base for an attractive wood finish is tricky. For one thing, its hard to sand without burning through, which will cause noticeable color changes when the topcoat is applied. And when the surface does fail, 85 percent of it will still be solidly stuck to the soft wood, and its removal or repair will be a major pain.

In our opinion, coating a mast with epoxy prior to varnishing and then topping off with a two-part coating is asking for more work down the road. The epoxy’s best attribute, its adhesive tenacity, is also its bane.

We recommend sticking with a good spar varnish. In our upcoming report in the July 2021 issue, testers noted that after two years of direct exposure, three traditional spar varnishes faired extremely well, showing exceptional gloss, and little signs of weathering. Testers also observed that three of the top-shelf synthetic acrylic urethane, and polyurethane finishes looked almost as good as new.

Doubling-up Protection

The most recent round of woodfinish testing did not combine different products (although some products were multi-component), so it did not look at the multi-product method many pros use to protect spars. This two-product method, which we’ve discussed previously, entails first applying a penetrating phenolic tung-oil based varnish (usually one-part) and then following it with a clear acrylic urethane, or polyurethane (usually two-part). This two-product approach results in a flexible clear coating that provides three layers of protection: sealing the wood from water penetration, providing UV protection, and enhancing the finish hardness. All of the major marine coating manufacturers, including Pettit, Epiphanes and International (Interlux), offer products that adapt well to this two-step method protection.

A classic example of this approach is Interlux’s Awlspar/Awlbrite system still used by many pros: Apply a few coats of Awlgrip’s Awlspar, an amber-hued phenolic tung-oil varnish, and then overcoat with Alwgrip Awlbrite, a clear acrylic urethane with three-component (base, converter, activator). Given the outstanding results of our most recent testing with newer, easier to apply products (including Interlux’s relatively new line of Awlwood products), this approach might not be best for the do-it-yourselfer, but it has a long track record among professionals.

In addition to our most recent report in the soon-to-be published July issue, Practical Sailor subscribers can see results of our long-term test of varnishes and other wood finishes in the May 2009 , January 2011 , and September 2011 issues. Our initial reports on one-part varnishes and two-part varnishes that appeared the August 2007 and December 2007 issues are available to all sailors, as is our January 2011 guide to selecting varnish types and December 2009 guide to maintaining varnish . To search our complete archives for past reports on varnishes and clear wood coatings, search under wood coatings, wood finish, or specific product names like Cetol.

And if varnish is just part of a more extensive cosmetic overhaul for your boat, then our four-volume series “ Painting Your Boat from Bottom to Top ,” offers details on every aspect of a complete makeover–from stripping old paint or varnish, to choosing new coatings and applying them for a professional finish.

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

I have a Atkin schooner with 2 sitka spruce masts and the two gaffs that are both varnished. I agree that annual inspections are critically required. (I have a self climbing system). Maybe 15 years ago, I stripped the masts when they were on the ground and put on 12 coats of varnish. After that I put one coat of Epifanes’s Woodfinish gloss then 1 coat of their traditional clear varnish. I follow Rebecca Wittman “The Brightwork Companion” for instructions on what to do when going up and back down the masts. The main mast takes a beating especially during panic reefing. But the varnish is flexible and you can monitor the damage. The main negative is you need a few days temperature to be over 70 F.

You mentioned Awlspar/Awlbrite with an overcoat with Alwgrip Awlbrite. What are your thoughts on Awlwood?

Awlwood did very well in our testing, earning a Recommended product rating. We’ve not used it — yet — on spars. https://www.practical-sailor.com/boat-maintenance/diy-projects/exterior-wood-finish-update-at-2-years

I have a Friendship Sloop and use Awlwood on everything, including spars (clear primer, then yellow primer added to gloss, then gloss), dug out all checks and filled with Sikaflex 201, tan, which is hard to see from 10′ and cures with the same chemistry as Awlwood, so no problems with adhesion of finish. Stuff lasts forever — 8 years and counting on lazarette hatches, horizontal to sun and never covered, looks brand new. I built roller sawhorses to ease spar finishing, cutting a slot in the top and fitting small (8″) rubber wheels on 1/2″ axles which are fastened to the top with 1/2″ copper plumber’s pipe fasteners and a small piece of 1/2″ copper pipe into which the axle fits. Made working on mast and finishing easy, just roll the mast which sits on two wheels per sawhorse. I would send a picture of mast and sawhorses, but can’t figure out how to.

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

How To Make Starlink Better On Your Boat | Interview

Catalina 380: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

WOODEN BOW TIES

How to build a wooden sailboat: a beginner's guide.

Are you interested in building your own sailboat? If so, building a wooden sailboat can be a rewarding and fulfilling experience. Not only will you have a unique vessel to call your own, but you’ll also learn valuable woodworking skills along the way.

To get started, you’ll need to gather the necessary materials and tools. This may include oak plywood, epoxy resin and hardener, thickener, brad nails, masking tape, a pull-saw, and a table saw. Once you have everything you need, you can begin the process of building your sailboat. From creating a jig and frame assembly to making the mast, there are many steps involved in building a wooden sailboat. But with patience and attention to detail, you can create a beautiful and functional vessel that will bring you joy for years to come.

Understanding the Basics of a Wooden Sailboat

If you are interested in building a wooden sailboat, it’s important to understand the basics of how a sailboat is constructed. In this section, we’ll cover the parts of a wooden sailboat and the different types of wooden sailboats.

Parts of a Wooden Sailboat

A wooden sailboat is made up of several parts, each with its own unique function. Here are some of the most important parts:

- Hull : The hull is the main body of the boat. It is the part of the boat that sits in the water and provides buoyancy.

- Keel : The keel is a long, narrow fin that extends down from the bottom of the hull. It helps to keep the boat from capsizing by providing stability.

- Rudder : The rudder is a flat piece of wood or metal that is attached to the back of the boat. It helps to steer the boat.

- Mast : The mast is a tall, vertical pole that supports the sails.

- Sails : The sails are large pieces of fabric that are attached to the mast and other parts of the boat. They catch the wind and propel the boat forward.

- Boom : The boom is a horizontal pole that is attached to the bottom of the mast. It helps to control the shape of the sail.

Types of Wooden Sailboats

There are many different types of wooden sailboats, each with its own unique characteristics. Here are some of the most common types:

- Dinghy : A dinghy is a small sailboat that is typically used for recreational sailing or racing.

- Sloop : A sloop is a sailboat with a single mast and a fore-and-aft rig.

- Ketch : A ketch is a sailboat with two masts, with the main mast taller than the mizzen mast.

- Yawl : A yawl is a sailboat with two masts, with the mizzen mast located aft of the rudder post.

When choosing a type of wooden sailboat to build, it’s important to consider your needs and experience level. A dinghy is a good choice for beginners, while a ketch or yawl may be more suitable for experienced sailors.

By understanding the basics of a wooden sailboat and the different types available, you can make an informed decision about which type of boat to build.

Choosing the Right Materials

When building a wooden sailboat, choosing the right materials is crucial to ensure the boat’s durability and performance. In this section, we will discuss the two most important materials you’ll need to choose: wood and sails/rigging materials.

Selecting the Right Wood

Choosing the right type of wood for your sailboat is critical. You want a wood that is strong, lightweight, and resistant to rot and decay. Some of the most popular types of wood used in sailboat building include:

- Cedar: Lightweight and easy to work with, cedar is an excellent choice for planking and decking.

- Mahogany: Strong and durable, mahogany is often used for building frames and keels.

- Oak: A dense and hard wood, oak is commonly used for building frames and planking.

When selecting your wood, make sure it is free of knots, cracks, and other defects that could weaken the boat’s structure. You should also consider the wood’s grain pattern, as this can affect the boat’s strength and appearance.

Choosing Sails and Rigging Materials

The type of sails and rigging materials you choose will depend on the type of sailboat you’re building and your sailing needs. Some of the most common materials used in sail and rigging construction include:

- Dacron: A strong and durable synthetic material, dacron is commonly used for sailcloth.

- Nylon: Lightweight and flexible, nylon is often used for spinnaker sails.

- Stainless Steel: Strong and corrosion-resistant, stainless steel is commonly used for rigging hardware.

When selecting your sails and rigging materials, consider the conditions you’ll be sailing in and the type of sailing you’ll be doing. For example, if you’ll be racing, you may want to choose lightweight sails and rigging materials that will help you achieve maximum speed. On the other hand, if you’ll be cruising, you may want to choose more durable materials that can withstand rougher conditions.

By choosing the right materials for your wooden sailboat, you can ensure that your boat is strong, durable, and performs well on the water.

Designing Your Sailboat

Before you start building your wooden sailboat, you need to design it. This will involve creating a blueprint and determining the size and shape of your boat.

Creating a Blueprint

Creating a blueprint is an essential step in designing your sailboat. It will help you visualize your boat and ensure that you have all the necessary components in place. You can create a blueprint using software such as AutoCAD or SketchUp, or you can draw it by hand.

When creating your blueprint, consider the following:

- The length, width, and height of your boat

- The position of the mast and sails

- The location of the rudder and keel

- The number of cabins and their layout

- The placement of any storage compartments or equipment

Determining the Size and Shape

The size and shape of your sailboat will depend on several factors, including your budget, the type of sailing you plan to do, and the number of people who will be on board.

Consider the following when determining the size and shape of your sailboat:

- The type of sailing you plan to do (coastal cruising, racing, etc.)

- The number of people who will be on board

- The amount of storage space you will need

- The amount of deck space you will need

- Your budget

Once you have determined the size and shape of your sailboat, you can start gathering materials and building your boat.

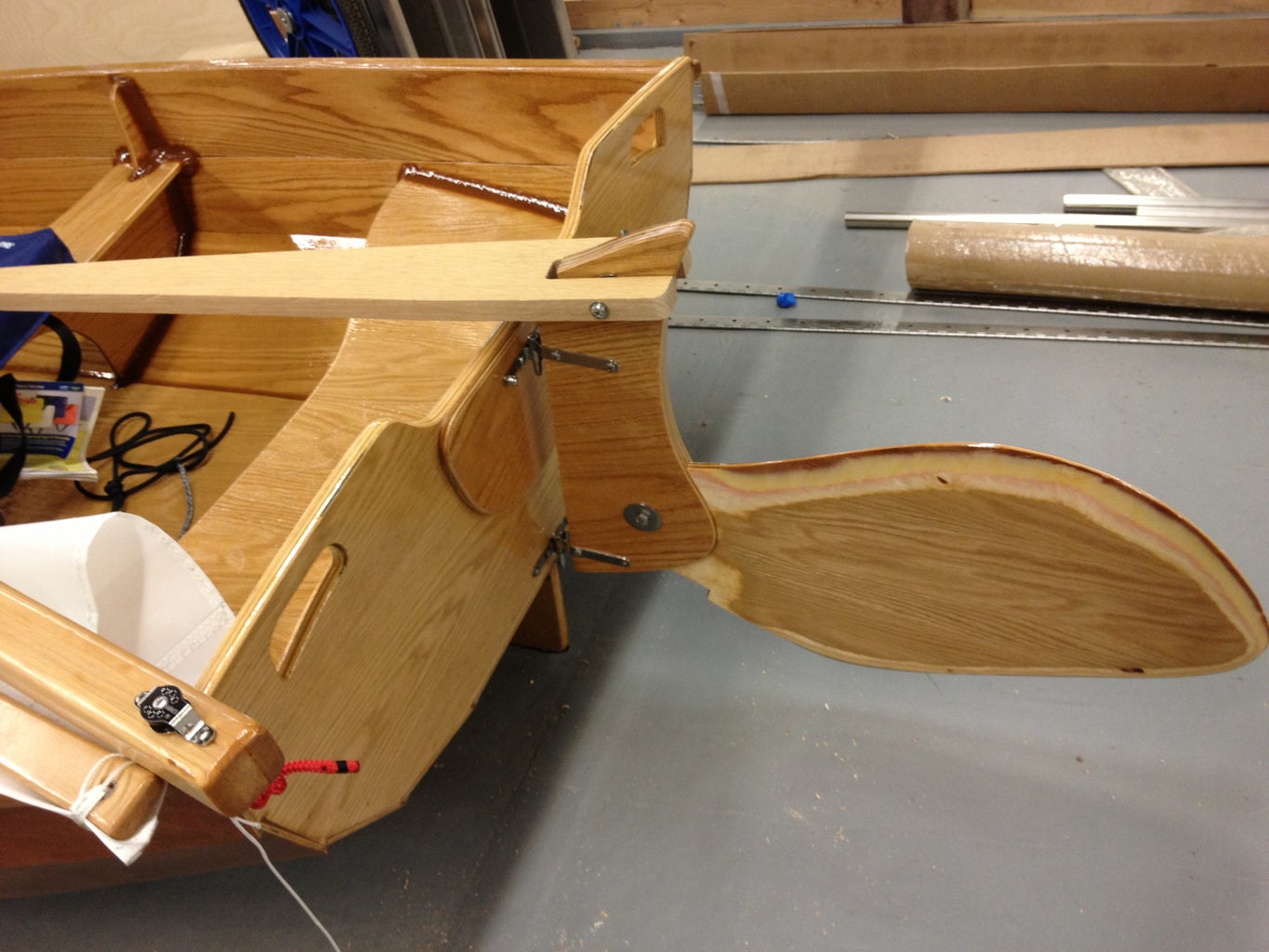

Building the Hull

When building a wooden sailboat, the hull is the most important part of the boat. It is the main structure that holds everything together and keeps the boat afloat. Building the hull requires cutting and assembling the wooden frame.

Cutting the Wood

To begin building the hull, you will need to cut the wood into the appropriate sizes and shapes. The wood should be cut according to the plans or blueprints that you have created. You can use a saw or a jigsaw to make the cuts.

It is important to use high-quality wood that is free of knots or other defects. The wood should be strong enough to withstand the pressure and weight of the water. Common types of wood used for building a wooden sailboat include cedar, oak, and mahogany.

Assembling the Frame

Once you have cut the wood, you can begin assembling the frame of the hull. The frame is made up of vertical pieces of wood called frames, which hold the shape of the boat. The frames are attached to the keel, which is the main structure that runs down the center of the boat.

To assemble the frame, you will need to use a sawhorse or other support to hold the lumber in place. You can then use screws or bolts to attach the frames to the keel. It is important to ensure that the frames are level and straight.

After the frames are attached to the keel, you can add the planks to the hull. The planks are attached to the frames and keel using screws or nails. It is important to ensure that the planks are properly aligned and spaced.

Once the planks are attached, you can sand and finish the hull to give it a smooth and polished look. This will also help to protect the wood from the elements.

Building the hull of a wooden sailboat requires patience and attention to detail. With the right tools and materials, you can create a strong and beautiful hull that will last for years to come.

Installing the Deck and Cabin

Installing the deck and cabin of your wooden sailboat is a crucial step in the construction process. It not only adds to the aesthetics of your boat but also provides structural support. Here are some tips to help you through the process.

Deck Installation

The deck of your wooden sailboat should be installed after the hull has been completed and before the cabin is built. It is important to ensure that the deck is watertight to prevent any leaks. Here are the steps to follow when installing the deck:

- Cut the deck to fit the hull and sand the edges to ensure a tight fit.

- Apply a layer of epoxy to the hull and deck joint to seal it.

- Secure the deck to the hull using screws or bolts.

- Apply a layer of fiberglass cloth and epoxy to the deck to make it watertight.

- Sand the surface of the deck to prepare it for painting or varnishing.

Cabin Installation

The cabin of your wooden sailboat provides shelter and storage space. It is important to ensure that it is properly installed to prevent any leaks. Here are the steps to follow when installing the cabin:

- Build the cabin on a flat surface using marine-grade plywood.

- Cut the cabin to fit the deck and hull and sand the edges to ensure a tight fit.

- Apply a layer of epoxy to the cabin and deck joint to seal it.

- Secure the cabin to the deck using screws or bolts.

- Apply a layer of fiberglass cloth and epoxy to the cabin to make it watertight.

- Install any windows, hatches, or doors in the cabin.

- Sand the surface of the cabin to prepare it for painting or varnishing.

By following these steps, you can ensure that your wooden sailboat’s deck and cabin are properly installed and watertight. This will not only make your boat look great but also ensure that you have a safe and enjoyable sailing experience.

Setting Up the Mast and Sails

Now that you have built your wooden sailboat, it is time to set up the mast and sails. This process may seem daunting, but with a little patience and attention to detail, you can have your boat ready to sail in no time.

Step 1: Install the Mast

The first step is to install the mast. Depending on the design of your boat, the mast may be a single piece or assembled from multiple sections. Make sure the mast is secured properly and is straight. Use a level to ensure the mast is vertical in both directions.

Step 2: Prepare the Sails

Next, prepare the sails. Make sure the sails are clean and free of any debris or damage. Attach the sail to the mast using the halyard, which is a rope used to raise and lower the sail. Make sure the sail is hoisted all the way to the top of the mast.

Step 3: Attach the Boom

Attach the boom to the mast and secure it with a boom vang, which is a rope used to control the angle of the boom. The boom is the horizontal spar that holds the bottom edge of the sail.

Step 4: Set the Sail

Once the boom is attached, set the sail. Adjust the angle of the boom and the sail to catch the wind and start moving. You can use the main sheet to control the angle of the sail and the boat’s speed.

Step 5: Trim the Sail

Finally, trim the sail to optimize its performance. This involves adjusting the sail’s shape and position to maximize its power and minimize drag. Use the sail controls, such as the cunningham and outhaul, to adjust the sail’s shape. Use the main sheet to control the sail’s position relative to the wind.

Congratulations! You have successfully set up the mast and sails of your wooden sailboat. Now it’s time to hit the water and enjoy the thrill of sailing.

Applying Finishing Touches

When it comes to building a wooden sailboat, applying the finishing touches is a crucial step that can make all the difference in the final product. Here are some tips and tricks to help you get the perfect finish.

Sanding and Finishing

Before you can apply any finish, you need to make sure the surface is smooth and free of imperfections. This means sanding the wood with progressively finer grits of sandpaper until you achieve the desired smoothness. Once you’ve finished sanding, you can apply a wood conditioner to help the wood absorb the finish more evenly.

When it comes to choosing a finish, you have several options. Some popular choices include varnish, paint, and oil. Varnish is a popular choice for wooden boats because it provides a durable, glossy finish that can withstand the harsh marine environment. Paint is another option, but it requires more maintenance than varnish and may not provide as much protection against the elements. Oil is a good choice if you want a more natural look, but it may not provide as much protection as varnish or paint.

Painting and Varnishing

If you decide to go with paint or varnish, there are a few things to keep in mind. First, make sure you apply the finish in a well-ventilated area to avoid inhaling fumes. Second, make sure you apply thin, even coats and allow each coat to dry completely before applying the next. This will help prevent drips and ensure a smooth finish.

When it comes to varnishing, it’s important to use a high-quality brush and work quickly to avoid brush marks. You may also want to consider using a foam brush for hard-to-reach areas. Once you’ve applied the final coat of varnish, you can buff the surface with a soft cloth to achieve a high-gloss finish.

Painting requires a different approach. You’ll need to choose the right type of paint for your boat and make sure you apply it evenly. If you’re painting a large area, you may want to consider using a paint sprayer to achieve a smooth, even finish. Once the paint has dried, you can apply a clear coat to protect the paint and give it a glossy finish.

In conclusion, applying the finishing touches to your wooden sailboat is an important step that requires careful attention to detail. By following these tips and using the right tools and materials, you can achieve a beautiful, long-lasting finish that will protect your boat and make it stand out on the water.

Safety Measures

When building a wooden sailboat, safety should always be your top priority. Here are some safety measures you should take to ensure a safe and successful build.

Installing Safety Equipment

Before you start building, make sure you have all the necessary safety equipment installed in your workshop. This includes fire extinguishers, smoke detectors, and first aid kits. You should also have a clear and unobstructed path to the exit in case of an emergency.

When working with power tools, always wear eye and ear protection, as well as a dust mask to protect your lungs. If you are using chemicals, make sure you are working in a well-ventilated area and wear gloves and a respirator if necessary.

Conducting a Safety Check

Before you start working on your sailboat, conduct a safety check to make sure everything is in order. Check that all tools and equipment are in good working order and that there are no loose or damaged parts. Make sure your work area is clean and free of clutter, and that all cords and cables are properly secured.

When working with wood, be aware of any knots or cracks in the wood that could weaken the structure of your sailboat. Use only high-quality marine-grade wood and be sure to follow the plans carefully to ensure a strong and safe boat.

By following these safety measures, you can ensure that your wooden sailboat build is a safe and enjoyable experience.

Maintaining Your Wooden Sailboat

Congratulations on building your own wooden sailboat! Now that you have a beautiful vessel, it’s important to keep it well-maintained to ensure its longevity and safety on the water.

Regular Maintenance

Regular maintenance is essential to keep your wooden sailboat in top condition. Here are some tips to keep in mind:

- Clean your boat regularly with a mild soap and water to prevent dirt and grime buildup.

- Check for any signs of damage, such as cracks, rot, or loose fittings, and address them promptly.

- Apply a fresh coat of varnish or paint every few years to protect the wood from the elements.

- Keep your boat covered when not in use to protect it from the sun and rain.

Seasonal Maintenance

In addition to regular maintenance, there are also some seasonal tasks that you should perform to keep your wooden sailboat in top condition:

- At the beginning of the season, inspect the hull for any damage or wear and make any necessary repairs.

- Check the rigging and sails to make sure they are in good condition and make any necessary repairs or replacements.

- Before storing your boat for the winter, make sure to properly winterize it to protect it from the cold and moisture.

Additional Tips

Here are some additional tips to keep in mind when maintaining your wooden sailboat:

- Use high-quality marine-grade products when cleaning and maintaining your boat.

- Avoid using harsh chemicals or abrasive materials that can damage the wood.

- Regularly check the bilge for any water buildup and pump it out as needed.

- Keep your boat well-ventilated to prevent moisture buildup and mold growth.

By following these tips, you can keep your wooden sailboat in top condition and enjoy many years of safe and fun sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

March / April Issue No. 297 Preview Now

Rotating Wing Masts—Part I

By reuel parker.

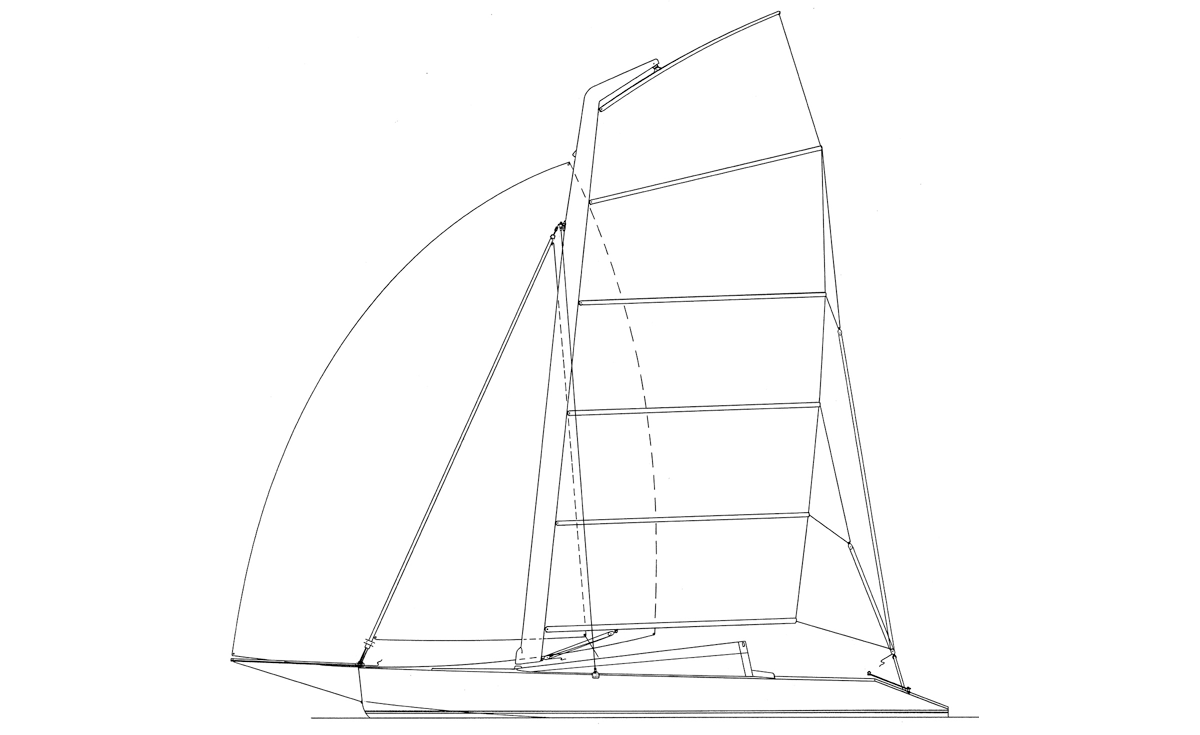

Conch 32 Sail Plan

In the late 1990s it occurred to me to design a trailerable one-design racer. I was living in Key West, and I also saw this as a way to get involved in Key West Race Week, a fairly major event in the world of fast sailboats.

Most small one-design racers have fin keels and require custom trailers, necessitating the use of a crane or Travel Lift to launch and haul them. Without very much knowledge or experience with one-design classes or rating rules, I simply dove into the project. I figured that one-design boats primarily race against each other, so I could design what I wanted… and I had a lot of ideas I wanted to try.

I designed the boat and rig during winter of 1997-8, but didn’t get around to designing the mast until early 1999. I named my design CONCH 32, after the giant, tasty undersea snails indigenous to most tropical and subtropical waters (including the Florida Keys). “Conch” (pronounced “Konk”) is also the knick-name for people born and raised in the lower Keys. Long-term transplants, like myself, who become faux “natives” are referred to as “fresh-water conchs”. The name seemed appropriate for a one-design class designed specifically to be raced in the Florida Keys. Also, my office and boat shop were located in the old Singleton sea food packing plant, which had recently been sold, and re-named The Conch Farm. We built a number of boats there, including the prototype Commuter 36 MAGIC, the three 28′ Swansea Pilot Schooners GLANCE, FRANK and SYLVIA, plus numerous small dinghies and sharpies.

I was hoping that the new owners of the property would endorse my new one-design class as a promotional gambit—perhaps even to the extent of financing one or two boats. Although they seemed excited about it at first, nothing ever happened.

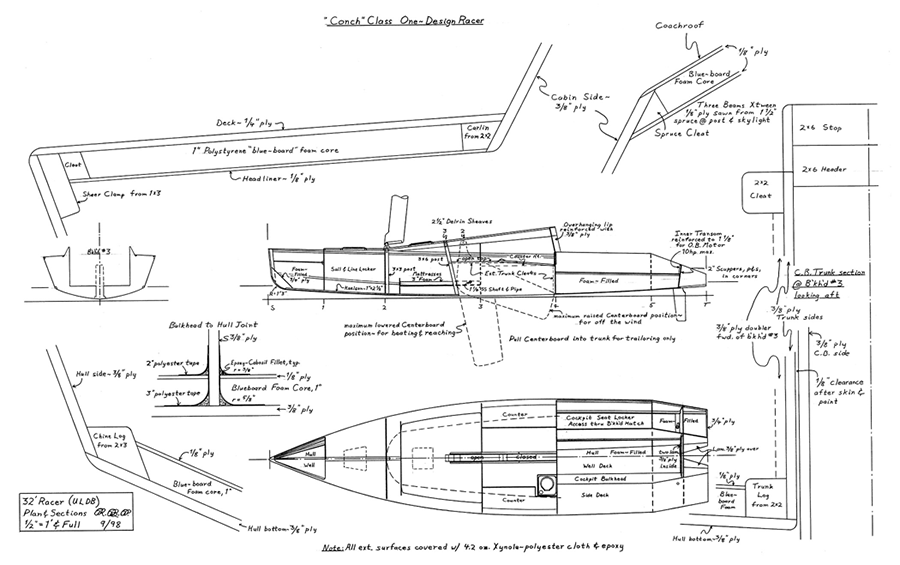

Plan & Construction Sections for the Conch 32.

To make the boat as light as possible, I incorporated polystyrene insulation foam in the hull and decks (Dow “blue-board”, which glues well with epoxy). The hull bottom is tortured marine plywood, arc-bottomed aft and V-bottomed forward. Beam is 8′ 6″ and displacement is 4,400 lbs, making this a trailerable boat. The NACA 0009 foil-shaped centerboard contains lead shot and polyester resin, and becomes a ballasted fin keel in the down position. The twin rudders are also foil-shaped.

The most unusual feature of new my hot-rod sailboat design was her mast. Rotating wing masts are very common in Key West, which is populated by a large number of charter catamarans (called “cattlemarans” locally). From studying and sailing on the big cats, I was intrigued by their rotating wing masts, and wondered why you never see them employed on mono-hulls… so I decided to try it myself.

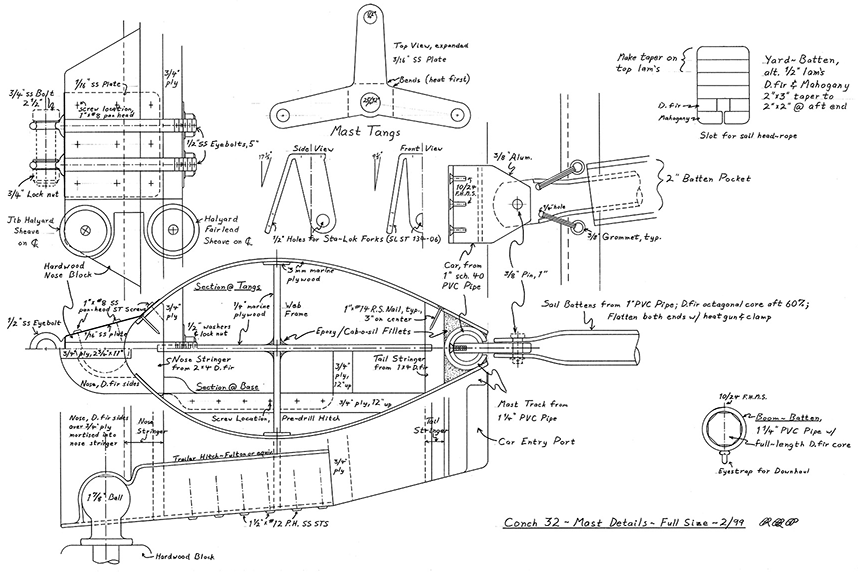

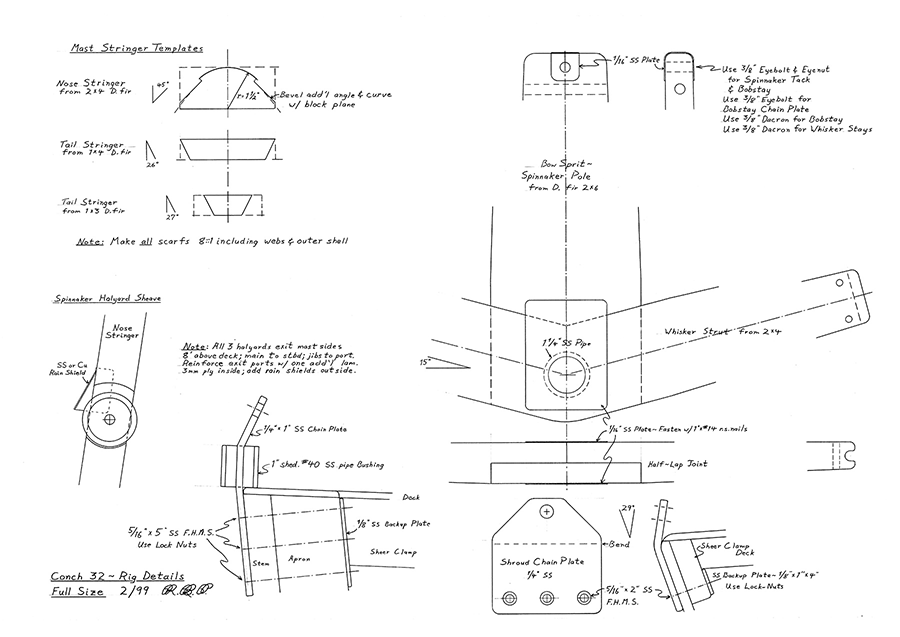

Construction Details for the Conch 32 lower mast.

Part of my concept for the Conch 32 was that she be easy and inexpensive to build—no exotic hardware! The few stainless steel components required can be made by a resourceful home-builder with a mini-grinder and bench vise. Mast track, sail-slides and sail battens can be made from standard PVC plumbing pipe and aluminum flat stock. The mast step ball joint employs a standard trailer hitch (a method used by several of the big charter cats). Sheaves use standard Schaefer Delrin replacement parts available from any chandlery or catalogue.

The idea behind rotating wing masts is that the mast fairs into the sail, like a real wing, instead of the sail coming off what is frequently the wrong part of the mast. Visualize a mains’l attached to a mast track on an oval-shaped mast while beam-reaching, and you get the picture. The mast becomes a flat block, contributing nothing but turbulence to overall sail shape. With a teardrop-shaped wing mast that is free to rotate, the mast acts like the foremost bones in a bird’s wing, or the leading edge of an airplane wing. It contributes to sail shape, rather than detracting from it. Many racing multihulls employ a “mast tiller” to further control the juxtaposition of mast to sail. This device is attached to the mast base, with control lines leading to the cockpit, allowing fine-tuning of mast/wing shape.

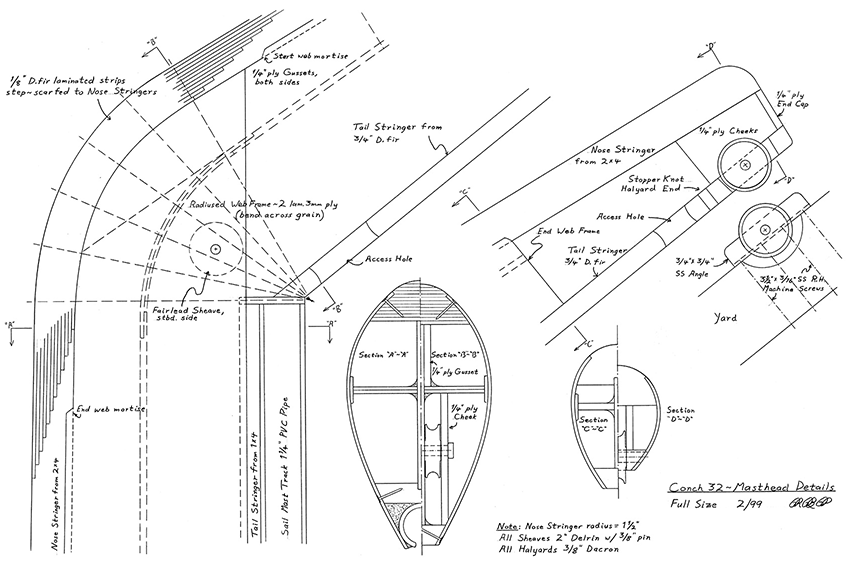

Construction Details for the Conch 32 upper mast.

This gave me the bright idea to put the mast tiller at the head of the mast, allowing the sail to automatically orient the mast optimally to the sail. I named my invention the “L-HEAD MAST”. I was also aware of a relatively new trend in sail shape, employing full-length sail battens near or even in the head of the sail. This creates a “Bat-Wing” effect, a trend which has become even more common today, fifteen years later. Some of these new sails even look suspiciously like gaff-riggers, although they aren’t! I might mention here that bat-wing sails have been commonly used on canoes, kayaks and wind surfers for many years.

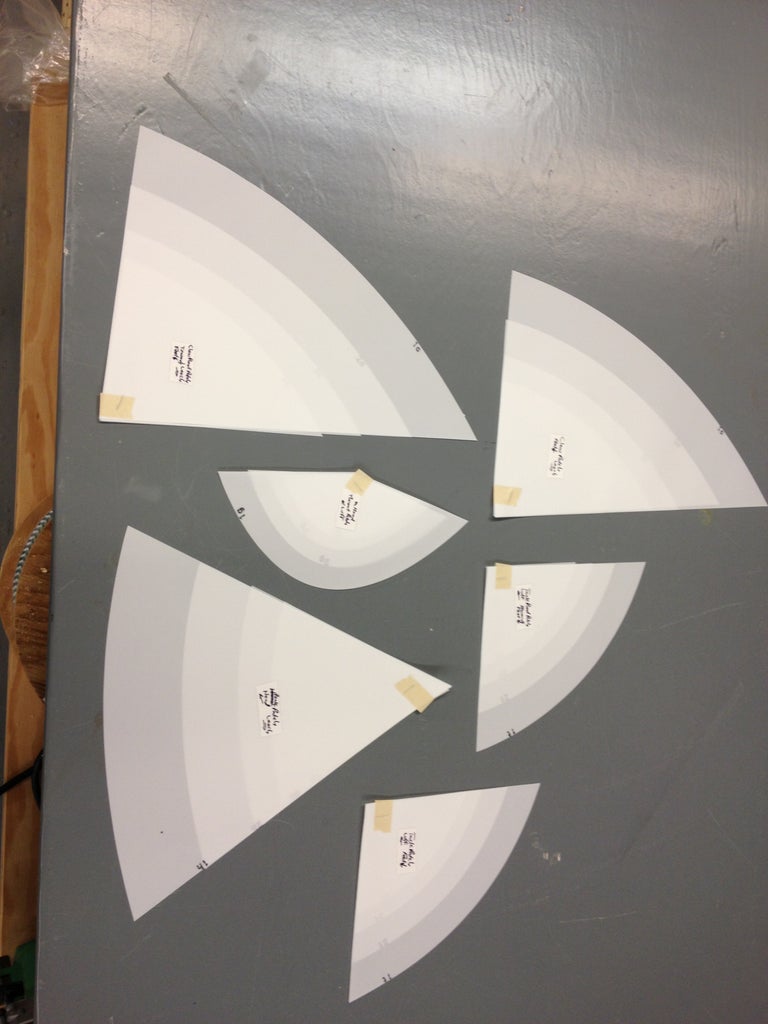

I wanted my new mast to be as simple as possible, but I had to find a way to make a structural bend near the top, to form the “L-head”… this I achieved with a stepped laminated nose stringer, and pie-shaped skin sections in way of the bend. I designed a mast core consisting of an internal plywood web frame coupled to solid stringers fore & aft. The mast can be made using nothing more exotic than a table saw. I used the web frame compartments for internal halyards, mounting sheaves in integral boxes. I eliminated the infamous “Jesus Shackle” (responsible for numerous dismasting accidents) in favor of standard SS eyebolts and a custom-made tang.

Rig details for the Conch 32.

I also designed a pivoting “bow sprit/spinnaker pole” for attaching a spinnaker tack, allowing the spinnaker to be shifted to windward on a broad reach, out from behind the mains’l.

Despite all the thought and design work I put into this project, it went over like a lead balloon! I have never sold a set of plans for the Conch 32, and one has never been built. I later designed a Conch 19 (a smaller version of the 32), and that one, also, vanished without a trace.

During this time I was avidly studying the Chinese Junk rig, which is where full-length battens for sails originated, and I began to see correlations between Junk sails, lug-rigged sails, full-length battens and multiple sheet leads. My sail plan for the Conch 32 combines various techniques from various rig types spanning centuries of time, all blended together to make something new.

In Part Two on this subject, I will address larger rotating wings employing more modern techniques and hardware, as applied to both monohulls and multihulls.

Jan 12, 2014, Saint Lucie Village

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe today.

Publishing dynamic editorial content on boat design construction, and repair for more than 40 years.

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

Print $39.95, digital $28.00, print+digital $42.95, from online exclusives.

Blacksmithing at the WoodenBoat School

Extended content.

MAUD Returns Home

From Lobsterboat to Lobster Yacht

From the community.

1968 Chris Craft Custom

1968 Chris Craft has been updated and customized for the classic boat lover.

50 years of WB, Sails, more

All original issues of WB, $375; Sails for sloop rig, new condition, luff 29’5” 2 jibs, bagged, $

1941 36' Stephens motor yacht

She's FREE to anyone who can take on the project.

Register of Wooden Boats

I aquired Maverick in November of 2023 for $1.

Step-By-Step Guide: How to Build a Wooden Sailboat – Complete DIY Tutorial

Alex Morgan

Building a wooden sailboat is a rewarding and fulfilling endeavor that allows you to create your own vessel for sailing adventures. Whether you’re a seasoned sailor or a woodworking enthusiast, constructing a wooden sailboat requires careful planning, attention to detail, and a love for craftsmanship. This comprehensive guide will take you through the step-by-step process of building a wooden sailboat, from choosing the right design and gathering the necessary materials to assembling the framework, building the deck and cabin, and installing the sails and rigging. We will also discuss the finishing touches and regular maintenance required to keep your wooden sailboat in optimal condition for years of enjoyment on the water. Let’s dive into the world of wooden sailboat construction and embark on this exciting journey together.

Key takeaways:

Key takeaway:

- Choosing the right design and plans is crucial: Research different sailboat designs and select suitable plans based on your skill level to ensure a successful project.

- Gather the necessary materials and tools: Pay attention to wood selection and preparation, as well as acquiring the tools and equipment needed for building your wooden sailboat.

- Attention to detail in the construction process is important: Prepare and assemble the framework carefully, focusing on lofting, laying out the keel, constructing the ribs, and the hull structure to ensure a sturdy and reliable sailboat.

Choosing the Right Design and Plans

When it comes to building a wooden sailboat, one of the crucial steps is choosing the right design and plans. In this section, we’ll take a deep dive into the world of sailboat designs and explore the vast array of options available. From researching different sailboat designs to selecting plans that match your skill level, we’ll guide you through the exciting process of bringing your wooden sailboat dream to life. So, hop aboard and let’s set sail on this exhilarating journey of craftsmanship and adventure.

Researching Different Sailboat Designs

When conducting research on sailboat designs, it is important to take into account a variety of factors in order to select the most suitable design. One of the primary considerations is whether you prefer a monohull or a multihull sailboat. Monohulls are more commonly found and offer superior performance when sailing upwind, whereas multihulls provide both stability and speed.

Another aspect to consider is your level of sailing experience. If you are a beginner, it is advisable to seek out designs that are easier to handle and forgiving. On the other hand, experienced sailors may gravitate towards performance-oriented designs that are ideal for racing or long-distance cruising.

It is crucial to think about how you intend to use the sailboat. Are you looking for a day sailer , a cruiser , or a racing boat ? Each design comes with its own set of distinctive features and characteristics.

Determining the appropriate size of the sailboat is another crucial step, which should be based on the number of people and activities you plan to have on board. You must also decide whether you prefer an open cockpit or an enclosed cabin .

To find the perfect sailboat design that aligns with your sailing goals and preferences, it is imperative to thoroughly research various options and take into consideration all of these factors. By doing so, you will be able to make an informed decision and select the ideal sailboat design.

Selecting Suitable Plans for Your Skill Level

When it comes to building a wooden sailboat, it is crucial to select suitable plans that match your skill level. This is important as it ensures that you have the necessary knowledge and expertise to effectively complete the construction. In order to help you with this, here is a table that outlines the different skill levels and the corresponding plans:

Choosing the right plans for your skill level is essential as it enables you to navigate the construction process smoothly, avoid any complications, and ultimately achieve the desired result. It is crucial to honestly evaluate your woodworking skills and then select plans that align with your abilities. Keep in mind that building a wooden sailboat demands patience , attention to detail , and a willingness to learn and improve your woodworking skills.

As a pro tip, if you are a beginner, it is advisable to start with simpler plans and gradually work your way up to more complex projects. This allows you to gain experience and confidence in your woodworking abilities over time. So always remember to select suitable plans for your skill level and enjoy the process of building your wooden sailboat.

Gathering the Necessary Materials and Tools

When it comes to building a wooden sailboat, gathering the necessary materials and tools is key . In this section, we’ll dive into the exciting world of selecting and preparing the right wood for your sailboat, as well as the essential tools and equipment you’ll need to bring your project to life. So, start sharpening your creativity and let’s sail away into the realm of wooden boat construction!

Wood Selection and Preparation

Incorporating the provided keywords naturally in the provided text:

1. Conduct research on the different types of wood used in boatbuilding, such as mahogany , teak , or oak . This will help you make an informed decision regarding the most suitable wood for your sailboat.

2. Determine the specific requirements of your sailboat design in order to guide your wood selection process. Each design may have different needs and preferences when it comes to the type of wood to be used.

3. Take into consideration the durability and resistance to rot of the wood options available. This is crucial to ensure the longevity and overall quality of your sailboat. Choosing a wood that can withstand exposure to water and other elements is essential.

4. Look for straight , dry , and defect-free wood. This will contribute to the structural integrity of your sailboat. Any defects or irregularities in the wood may compromise its strength and performance.

5. Calculate the amount of wood needed based on the specific design and measurements of your sailboat. This will help you estimate the quantity of wood required for the construction process.

6. Mill or cut the wood into the required dimensions and shapes as outlined in the sailboat design. This step is crucial for achieving the desired structure and appearance of your sailboat.

7. Prior to assembly, it is important to sand the wood surfaces thoroughly. This will remove any rough edges or splinters, ensuring a smooth and safe finish.

8. Apply a protective coating or sealant to the wood in order to prevent water damage. This will help preserve the wood and extend its lifespan .

By following these steps, you can ensure that the wood selected and prepared for your sailboat construction is suitable and of high quality.

Tools and Equipment Needed for the Project

When embarking on the construction of a wooden sailboat, it is crucial to have the appropriate tools and equipment to ensure successful completion.

To accurately measure and obtain precise alignment and dimensions, essential measuring tools such as a tape measure , combination square , and level are indispensable.

For shaping wooden components, cutting tools like a circular saw or table saw , jigsaw , and hand saw are necessary.

Joinery tools, including a chisel set , mallet or hammer , and drill with different-sized bits, are vital for smoothly joining parts together.

To achieve a polished finish, sanding and finishing tools such as sandpaper with varying grits, sanding blocks , and a random orbital sander are crucial.

Additionally, brushes and rollers are required for the application of finishes.

When it comes to safety, it is imperative to prioritize the use of safety goggles , ear protection , a dust mask , and work gloves to ensure personal protection during the construction process.

When selecting tools and equipment, it is essential to invest in high-quality items that are specifically designed for the tasks involved in wooden sailboat building.

By doing so, not only will efficiency be maximized, but the overall quality of the finished boat will also be greatly enhanced.

Preparing and Assembling the Framework

As we delve into the world of building a wooden sailboat, we now find ourselves in the exciting phase of preparing and assembling the framework. In this section, we’ll discover the essential steps that go into setting up the lofting and laying out the keel , as well as the intricacies of constructing the ribs and hull structure. Get ready to immerse yourself in the hands-on process of bringing this magnificent vessel to life!

Setting Up the Lofting and Laying Out the Keel

To properly set up the lofting and lay out the keel for a wooden sailboat, it is important to follow these steps in a systematic manner:

- Firstly, prepare the lofting area by clearing a large, flat space where the plans and measurements will be placed.

- Next, securely attach the keel stock to the lofting platform, making sure it is both level and aligned with the boat’s centerline.

- Using battens, rulers, and pencils, transfer the measurements and lines from the boat plans onto the lofting platform.

- Ensure the accuracy of the waterlines, buttock lines, and other reference lines on the lofting platform by drawing them according to the measurements provided in the boat plans.

- Utilizing the dimensions indicated in the plans, measure and mark the positions of the keel, stem, and transom on the lofting platform.

- Thoroughly examine and adjust all lines and measurements to guarantee their accuracy.

- Identify the locations where any additional frames, bulkheads, or structural elements will connect to the keel, by marking them accordingly.

- Prior to proceeding, double-check all marks and measurements to ensure their accuracy.

The process of setting up the lofting and laying out the keel is an integral step in the construction of a wooden sailboat. It serves as the foundation and reference points for the boat’s overall structure. It is crucial to pay close attention to detail and maintain accuracy throughout the build. By following these steps, you will be on your way to constructing your very own wooden sailboat.

Constructing the Ribs and Hull Structure

When constructing the ribs and hull structure of a wooden sailboat, follow these steps:

– Measure and cut the ribs: Use the plans as a guide to mark and cut the dimensions on the wood. Cut the ribs accurately.

– Attach the ribs to the keel: Position and attach the cut ribs evenly along the keel using marine epoxy and screws.

– Install chines and stringers: Attach the chines to the bottom edge of the boat and install the stringers along the sides for strength.

– Attach the planking: Cut and fit planks to cover the rib and stringer structure, securing them tightly.

– Reinforce the joints: Apply epoxy and fiberglass tape over the joints to strengthen the structure.

– Shape the hull: Use tools to shape and smooth the hull, paying attention to fairing for optimal hydrodynamics.

– Apply a protective finish: Coat the hull and ribs with marine-grade varnish or epoxy for durability.

– Perform a thorough inspection: Check for defects, cracks, or imperfections and make necessary repairs before moving forward.

The process of constructing wooden sailboats has evolved over time, combining traditional techniques with modern materials and tools. Craftsmanship, attention to detail, and an understanding of wood’s properties are still essential in constructing the ribs and hull structure. This blend of artistry and engineering ensures sailboats can withstand the demands of the sea while providing a smooth and enjoyable sailing experience.

Building the Deck and Cabin

Let’s dive into the exciting world of building a wooden sailboat! In this section, we’ll focus on the crucial element of constructing the deck and cabin. Get ready to explore the process of creating the deck framework and adding those essential interior features . From laying the foundation to crafting a cozy cabin space , we’ll uncover the key steps and considerations for bringing your wooden sailboat to life. So, grab your tools and let’s set sail on this exhilarating construction journey !

Creating the Deck Framework

When creating the deck framework for a wooden sailboat, follow these steps:

- Measure and mark the desired deck size and shape on the boat’s frame.

- Cut and shape the wooden planks or panels to match the marked measurements.

- Align the planks or panels horizontally across the frame, ensuring they are straight and evenly spaced.

- Secure the planks or panels to the frame using screws or nails, ensuring tight fastening.

- Add additional support beams or joists underneath the deck for added strength and stability.

- Sand the deck surface to create a smooth and even finish.

- Apply a weather-resistant sealant or paint to protect the deck from moisture and UV damage.

- Install necessary features or fixtures on the deck, such as hatches, cleats or railings.

Pro-tip: Enhance the deck’s strength and durability by adding epoxy or marine adhesive between the joints before securing the planks or panels.

Installing the Cabin and Interior Features

When building a wooden sailboat, it is important to pay attention to every step, including the installation of the cabin and interior features. To install these features, follow the following steps:

1. First, measure and cut the materials for the cabin walls, floor, and ceiling.

2. Next, securely fit the cabin walls in place.

3. Then, attach the floorboards to the cabin base using screws or nails.

4. Align and install the cabin ceiling.

5. If desired, add insulation for extra comfort.

6. Attach interior features such as cabinets, storage compartments, and seating areas.

7. Install windows and hatches to allow for natural light and ventilation.

8. Properly wire the cabin for electricity, ensuring that lights and outlets are installed and functioning.

9. Finish the interior by sanding and applying a protective coat of varnish or paint.

10. Ensure that all installations meet safety standards.

Precision and attention to detail are key when installing the cabin and interior features of a wooden sailboat. By carefully measuring, cutting, and fitting each component, you can ensure a secure fit. It is important to optimize the layout and functionality of the interior features to create a comfortable living space with ample storage. The addition of windows and hatches will enhance comfort and enjoyment by providing natural light and ventilation . If electricity is needed, proper wiring is essential to ensure necessary lighting and power outlets. Finishing the interior with a protective coat of varnish or paint will not only enhance aesthetics but also provide durability.

Remember, the goal is to create a cozy retreat for sailors, so it is important to put in the necessary effort to install the cabin and interior features correctly.

Installing the Sails and Rigging

Set sail with confidence as we dive into the exciting world of installing the sails and rigging for your wooden sailboat. Discover the key considerations in choosing the perfect sails and master the art of setting up and adjusting the rigging. With expert tips and tricks , this section will equip you with the knowledge to navigate the waters with ease and experience the thrill of sailing your wooden masterpiece .

Choosing the Right Sails

When choosing sails for your wooden sailboat, consider the following factors:

– Type of sailing: Determine if you plan to cruise , race , or do both. Different sails are designed for specific purposes.

– Boat size: The size of your sailboat determines the size and number of sails you need. Larger boats require bigger sails , while smaller boats may need fewer and smaller sails .

– Wind conditions: Consider the typical wind conditions in your sailing areas. Different sails perform better in light winds , heavy winds , or various wind conditions.

– Sail material: The material of the sails affects durability and performance. Material choices include Dacron , laminate , and nylon . Each material has different trade-offs between longevity, performance, and cost.

– Reefing options: If you sail in varied or unpredictable wind conditions, choose sails with reefing options. Reefing allows you to adjust the sail area for stronger winds, improving control and safety.

– Manufacturer reputation: Research sail manufacturers for their reputation and reliability. Read reviews, seek recommendations, and consider warranty and customer support.

By considering these factors, you can make an informed decision when choosing sails for your wooden sailboat. Remember, the right sails greatly impact your sailing experience, so take your time and choose wisely.

Setting Up and Adjusting the Rigging

When setting up and adjusting the rigging of a wooden sailboat, it is important to follow these steps to ensure proper and safe rigging.

To start, attach the mast to the deck using a mast step or mast partner for stability and support. This will provide the foundation for the rigging.

Next, secure the standing rigging , which includes the shrouds and stays , to the mast. This will help distribute the forces from the sails and ensure the stability of the mast.

Connect the forestay to the bow of the sailboat. This will keep the mast in line and control the position of the headsail.

To counteract forces from the headsail and maintain rigging tension, attach the backstay to the stern of the boat.

Use turnbuckles or rigging screws to adjust the tension in the standing rigging. This will ensure proper alignment and support of the mast.

Install the running rigging , including halyards and sheets , to control the position and tension of the sails.

Before and during sailing, it is important to regularly check the tension in the rigging to ensure performance and safety.

Make any necessary adjustments to the rigging during sailing in order to optimize the shape of the sails and enhance the performance of the boat.

By following these steps, you will be able to properly set up and adjust the rigging of your wooden sailboat, allowing for safe and enjoyable sailing experiences.

Finishing Touches and Maintenance

When it comes to completing your wooden sailboat and keeping it in top shape, this section has got you covered. We’ll dive into the art of applying exquisite finishes to the hull and deck, giving your sailboat a stunning appearance. And don’t worry, we won’t neglect the nitty-gritty details of regular maintenance and care, ensuring your wooden vessel remains seaworthy for years to come. So, let’s get ready to add those finishing touches and keep your sailboat sailing smoothly !

Applying Finishes to the Hull and Deck

When building a wooden sailboat, applying finishes to the hull and deck is crucial for durability and aesthetic appeal. Here are the steps to follow:

1. Prepare the surfaces: Sand down rough spots, fill in cracks and imperfections, and ensure a smooth and clean surface.

2. Choose the right finish: Consider the type of wood and desired look. Varnish provides a glossy and traditional appearance, while paint offers different colors and styles.

3. Apply the primer: Enhance adherence and create an even surface for the final coat by applying a primer.

4. Apply the finish: Use a brush or roller to apply the chosen finish coat to the hull and deck. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for drying times and application techniques.

5. Allow for drying and curing: Follow the manufacturer’s instructions for drying and curing to ensure the finish is fully set and provides maximum protection.

6. Inspect and touch up: After drying, inspect the hull and deck for missed spots or imperfections. Touch up any areas that require additional finish for a seamless and polished look.

By following these steps and applying finishes properly, you can protect and enhance the hull and deck of your wooden sailboat, ensuring it looks beautiful and lasts for many years.

Regular Maintenance and Care for Your Wooden Sailboat

Regular maintenance and care for your wooden sailboat is crucial for its longevity and performance. Here are the steps to follow: