Laurent Gilles WANDERER III

Sail Number:

Type: Sloop

Wanderer III Specifications:

LOA: 30’3″ / 9.22m – LOD: 30’3″ / 9.22m – LWL: 26’5″ / 8.05m – Beam: 8’5″ / 2.56m – Draft: 5’0″ / 1.52m – Design Number: 39 – Designer: Laurent Gilles – Original Owner: Eric Hiscock – Current Owner: Thies and Kicki Matzen – Year Launched: 1952 – Built By: William King, Burnham-on-Crouch, UK – Hull Material: Wood – Gross Displacement: 7.2 tonns – Sail Area: 600 sq ft / 55.74 sq m

Historical:

Wanderer III, a 30-foot (9.1 m) Laurent Giles sloop, carried the Hiscocks around the world via the tropics at a time when few people were cruising the world for pleasure on small sailboats. The voyage and book accorded them a degree of popular celebrity, and was the first of their three circumnavigations. It was also the start of a series of books detailing their later voyages on their sailboats Wanderer III, Wanderer IV and Wanderer V. The trips in Wanderer III, together with previous voyages, provided much technical information for his technical how-to volumes on small boat sailing and ocean cruising, Cruising Under Sail and Voyaging Under Sail (later combined and published as Cruising Under Sail).

About the Video

Thies Matzen and Kicki Erickson, longtime adventure sailors and current owners of Wanderer III talk about the boat and their 30 years of adventure sailing aboard her. Twice circumnavigators, Lin & Larry Pardey talk about their friendship with the Hiscocks when they were young cruisers just starting out, what they learned from them, and the Hiscock’s accomplishments aboard Wanderer III.

The original owner of Wanderer III, British Sailors, Eric and Susan Hiscock became pioneers in making long trans-oceanic passages in a small sailboat to what was then quite remote destinations. The Hiscocks shared their sailing adventures in several books and made “Beyond the West Horizon,” a 16mm color documentary about their 3-year circumnavigation aboard their 30 foot wooden sloop, Wanderer III. Available from TheSailingChannel.TV.

Provenance (The Wall of Remembrance – The Owners, Crew & Notable Guest):

Owner/Guardian: (1952) Eric Hiscock Owner/Guardian: Thies and Kicki Matzen

Related posts:

- Grenada Commits to RORC Transatlantic Race

- Sailing Baby Blue: Episode 1 – Maine to Florida

- Hinckley Acquires Morris Yachts

- Samsø, Denmark – Sustainable Independence

Leave a Comment Cancel

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Email Address:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

March / April Issue No. 297 Preview Now

WANDERER III

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe today.

Subscribe by February 10th and your subscription will start with the March/April 2024 (No. 297) of WoodenBoat .

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

Print $39.95, digital $28.00, print+digital $42.95.

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

From Online Exclusives

Whiskey plank.

Visiting Bahamian Ruins By Boat—Part I

Extended content.

CREDIMUS: A documentary on an unlikely path to an unlikely race

Sheathing a Tired, Old Hull

HERMIONE Visits Castine, Maine

From the community.

1968 Chris Craft Custom

1968 Chris Craft has been updated and customized for the classic boat lover.

50 years of WB, Sails, more

All original issues of WB, $375; Sails for sloop rig, new condition, luff 29’5” 2 jibs, bagged, $

1941 36' Stephens motor yacht

She's FREE to anyone who can take on the project.

Register of Wooden Boats

I aquired Maverick in November of 2023 for $1.

No products in the basket.

Wanderer III

$ 35.00 – $ 1,020.00

Design No. 0164

Built for: Eric & Susan Hiscock Builder: W. M. King, Burnham on Crouch, England Date designed: 1951

Principal Design Data

L.O.A: 30’ 3½” (9.23 m) Datum: 26’ 4½” (8.04 m) Beam Max: 8’ 5” (2.56 m) Draft: 5’ 0” (1.52 m) Displacement tons: T.M.: 8.0 tons Ballast ratio: Sail Area: 597.0 sq. ft Rig: Bermudan sloop

After many years of sailing their 1936 Napier built cutter Wanderer II , Eric and Susan Hiscock naturally turned to Laurent Giles & partners for her successor Wanderer III .

One of Eric Hiscock’s main design specifications to Laurent Giles was that Wanderer III must have as much volume as possible for a given cost. This therefore dictated a moderate forward overhang with a transom stern, and had the advantage of being able to fit a trim tab vane steering gear which would be necessary for short-handed ocean passages. Although it was widely believed that Laurent Giles based the lines of the hull on an existing yacht Kalliste a 7-tonner built in 1938 information in the Laurent Giles Archive has recently revealed that the lines were actually developed from those of the 26’ 3” w.l. one design sloop which Giles had designed a year before in 1950 as a replacement for Kalliste for Mr D. W. Le Mare.

We are currently updating the online purchase facility. For those of you who would like to buy copies of the original historical drawings, plan for the construction of scale models, stock plan sets for full size construction, study notes or our brochure please contact us stating which design and items you require. We will do our best to help.

If you want to make your purchase by using PayPal account or credit card, please choose 'PayPal' at the 'Check out'. We can also take payment by Bank transfer, for further information, please contact us.

Additional Information

Individual drawing copies.

Please download and print the drawings list for Wanderer III, Individual plan copies cost $85.00 which includes standard airmail. Please contact us using the link for information on how to order.

Study Notes

16 page A4 format colour booklet containing many small scale drawings and photographs as well as technical data and an abridged specifications of Wanderer III. Construction scantlings are of the original carvel hull.

Model Plans

Full set of Stock Building Plans

A replica of Wanderer III can be constructed from the original 1951 drawings for carvel construction for which full lofting, construction, rigging and outfit drawings will be provided.

Poster & Art Prints

You may also like, check out a few related products.

"Wanderer III" : A cruising yacht classic and the 96th degree of longitude

YACHT-Redaktion

· 02.09.2023

From Thies Matzen

Take: an old boat, a remote longitude in the Pacific, three couples. Add: a less connected and consumed world; letters and boats instead of bytes carrying messages around a more analogue world; plenty of salt. Set the temperature to an average of 25ºC; wait seventy years - and this story of "Wanderer III" at longitude 96ºW begins to reach deep back into a sailing era when readers still took time to read articles of the length of this one.

The boats, on the other hand, were rather short. By today's standards, it takes some imagination to picture the nine metres and twenty-seven of "Wanderer III" as a comfortable living space - but that's exactly what they have been to us for forty years. And nobody could have guessed in 1952, when she glided into her element at her launch in Burnham-on-Crouch, England, that she would one day be credited with an affinity for a Pacific longitude. And that seventy years later, in the midst of the great outdoors of the Falkland Islands, she would be waiting on a mooring specially laid for her and still be ready to sail to it again. Just like that - it would be the ninth time.

Most read articles

No other yacht has characterised the beginning of cruising sailing as much as this 30-foot wooden boat. Hardly any other yacht has travelled the world as far and wide as she has. She has been honoured twice with the prestigious Blue Water Medal, which has been awarded annually since 1922, for her voyages, which have shaped the sailing of an entire era. First in 1955 with the British sailing couple Eric and Susan Hiscock and then in 2011 with us.

"Wanderer III" has a way of persuading the owners to sail around the world

Yet "Wanderer III" is by no means the best, fastest, most comfortable or even that elusive ideal cruising yacht. But there is something about her that has kept her three blue-water owners - Eric and Susan Hiscock, Gisel Ahlers with partner Chantal Jourdan and my wife Kicki and me - sailing her around the world almost continuously for seventy years.

The pencil crosses represented nothing less than eight unique sea moments on it, spanning over half a century. What exactly had allowed "Wanderer III" to create them again and again? What exactly had enabled her to survive two reef strandings, a capsize, several knock-downs and countless storms over more than 300,000 nautical miles sailed?

On the 14th day of their first passage in the Pacific in 1953 - from Panama to the Marquesas on the trade wind route around the world - the perennial bananas in the forepeak were overripe. "Falling like leaves in autumn," Eric wrote almost poetically in the logbook on 8 February 1953. His notes are astonishingly informal, less formal, they do without many technical lists of quantifiable values on air pressure, wind and weather, but are narrative; in words instead of numbers, with a note of the daily midday position.

First Pacific passage for "Wanderer III" is a tough one

But at 4º 41'S/96º 08'W the poetry was over: "The movement is terrible. For breakfast, the cooker, complete with kettle and pot of boiling water, ripped itself off its gimbal. Threw away the last bananas." And shortly afterwards: "The movement is just too much."

After 1,482 of the 4,000 nautical mile passage, they had long passed the Galapagos Islands. The wind had increased steadily throughout the night and they were pushing westwards at six knots.

"I tried to make her self-steering with the main furled and the jib held back ... but she turns out not to be well-balanced and only holds her course for a few seconds in a beam reach. Giles should study the 'metacentric shelf'."

"Back to the drawing board, Giles," Eric seems to suggest to the boat designer of the "Wanderer III", Laurent Giles, about a year after her launch. This is almost heresy and not typical of Eric. But at this moment in the logbook entry, he doesn't seem to have been very cheerful.

"The sky is mostly overcast. This is not what I imagined the south-east trade wind to be like. A gloomy day. Before dinner we reef down to the second reef. Susan is very tired, and she had the first night watch but couldn't sleep, while I could barely stay awake on deck."

"Wanderer's" fast, jerky movements and the strain of constant hand steering with the resulting lack of sleep dominate the entries in the logbook. Wind steering systems did not yet exist. Sleep was rare in the under-manned blue water sailing of the fifties.

"Wanderer III" hardly seems suitable for the high latitudes for the Hiscocks

Downwind, her long keel and large lateral plan "Wanderer III" hold her course well, and two identical headsails, one on port and one on starboard, effortlessly stabilise the course downwind. However, I have never had to steer by hand for any length of time on long passages, as I still have the services of her first windvane to fall back on. It is one of the two prototypes that its inventor Blondie Hasler installed simultaneously on his famous folk boat "Jester" and on "Wanderer III" in the mid-sixties. It has logged more than 230,000 nautical miles to date, still with original parts. It is simple, has never caused any problems and still makes me believe that "Wanderer" is perfectly balanced.

At their first meeting with longitude 96º W, however, Eric and Susan clearly disagreed. It wasn't until well after halfway to Nuku Hiva that they were finally able to celebrate a perfect sailing day - on a Friday the 13th - on the forecastle with rum punch and tinned salted peanuts.

After her first circumnavigation, her owner Eric Hiscock mused: "'Wanderer III' is surely the smallest boat in which a level-headed person with genuine respect for the sea would want to cruise an ocean."

"Wanderer III" is a mirror of the times

The knowledge and mindset of the fifties characterised their design. Nobody knew exactly how small a boat could be to get it safely around the world; and how strong it had to be built. This was countered with larger dimensions in critical areas - in the bilge, the mast area - and with a myriad of stiffening bulkheads integrated with fore-and-aft guides. The British liked their yachts compartmentalised and not open.

The 9.27 metre long "Wanderer III" is only 2.56 metres wide - for the simple, almost ridiculous reason that the construction price of a yacht in 1952 was based on the Thames Tonnage used at the time; and this in turn weighted the width excessively, so narrow was synonymous with cheaper. Moreover, nobody questioned why a nine-tonne yacht should have to carry around three tonnes of lead for its entire life. But after "Wanderer's" first circumnavigation, Eric did just that. Under the impression of her sleep-killing lurching and rolling and the encounters with wider American yachts with a shallower draught, his preferences changed.

His "ideal yacht", he wrote in 1957, was on the one hand "the largest one could afford, but with a limit of 15 tonnes displacement". In other words, about 40 feet long, eleven feet wide, with a draught of slightly less than 1.80 metres. Aft with a short, overhanging transom for more buoyancy as a direct response to the wet cockpit of his third "Wanderer". With space on deck where you can sleep outside in the tropics - much missed on the "Drei"; a cutter rig with a short bowsprit - for plenty of sailing power; and with plenty of engine power - anything bigger than the 4 hp Stuart-Turner of the "Drei". In short: a type of boat of which thousands were to be built in the seventies and eighties, although most of them were made of fibreglass.

For Eric, this was little more than a mental exercise at the time; he and Susan could not afford such a ship. And why should they? The "Three" had fully confirmed their trust and never let them down once.

Susan and Eric become repeat offenders

In 1959, they set off from England on their second circumnavigation, again along the classic circumnavigation route, soon christened the "Hiscock Highway". This time they set course for Mangareva in the East Pacific and crossed the 96th meridian a little further south than the first time. And again it gave them quite a hard time.

"At Susan's suggestion we turned in for six hours so we could both get some sleep. Took the jib down at 0600, unbelievable rolling at times, it even catapulted a saucer out of its holder. Everything is the wrong way round on this bow: galley to windward instead of leeward makes cooking extremely difficult, chart table to leeward sends blood to my head - and, as we both prefer to sleep on the right side of our bodies, our faces are pressed hard onto the mattress and our elbows, which were causing us problems before, are paralysed ... Susan's stomach is better, mine is still annoying."

This logbook entry from 6 March 1960 makes me wonder: How can it be that I hardly feel this rolling and lurching? Am I really so insensitive and insensitive to movement? Or have I - since I hardly ever had to steer by hand on long voyages, except in polar waters with drift ice - simply never experienced the same excessive and continuous exhaustion as she did?

Despite shortcomings, "Wanderer III" remains favourite yacht

Laurent Giles gave his own answer to the apparent shortcomings of the "Wanderer III" with the design of his 30-foot Wanderer class. It is slightly wider, with a higher freeboard, a continuous deckhouse instead of the stepped one, and therefore with a larger cabin. I have never sailed a Wanderer-class boat, but in purely aesthetic terms - for me - there is simply no comparison with the "Drei".

Eric's lamentations may ultimately have prevented the "Wanderer III" from becoming a popular design with a correspondingly large number of replicas - which would have been expected, given that her voyages inspired entire generations of sailors worldwide. And yet, after 110,000 nautical miles sailed together and despite all the misfortunes at 96º W, she remained Eric and Susan's declared favourite yacht for the rest of their lives.

Third circumnavigation with new owners

Between 1974 and 1979, Gisel and Chantal sailed "Wanderer III" around the world for a third time. Unlike Eric and now me, Gisel hardly ever wrote a word and took very few photographs. Nevertheless, of the three of us, he is the real storyteller. His powers of observation and ability to immerse himself in the smallest details and convey them across a table over hot tea and fresh brown bread are unrivalled. He tells wonderfully intricate stories that are a pleasure to listen to, but not to read. That's how I got to know him in Kiel in 1982: as a storyteller and - it felt like - the only German with an inordinate amount of time.

Not long before I met him for the first time, he had sailed "Wanderer III" single-handed through the Indian Ocean while his partner Chantal was ferrying another yacht - and tragically died in the process. After 15 years of long-distance sailing, most recently on "Wanderer III", Gisel said he would probably not be sailing for a while. I left him a phone number - he had dialled it later that year and said he wanted me to keep "Wanderer III" moving on the oceans. It determined the direction of my life.

Today, in his mid-seventies, he lives on Mallorca, where I last met him. Apart from the encounter in a crazy dream in which he made the astonishing remark: "Thies, I forgot to tell you that 'Wanderer' has a cellar", I hadn't seen him for a whole eight years.

Few footprints of Gisel and Chantal

That mysterious extra storage space had unfortunately remained as much in the dark as parts of his "Wanderer" story. I only had one tiny clue about Gisel and Chantal's rendezvous at 96º W: the sketch of a freighter near the equator on the chart of the Eastern Pacific that he had passed on to me.

There stood Gisel on Mallorca, tall and slim, a warm smile on his face, his upper body slightly bent forward as always; he carried this adaptation of "Wanderer's" small dimensions into his later life. Both Gisel and Chantal were too tall to fit into the Wanderer III, which was designed for the shorter Hiscocks. They could not stand upright in the cabin and could not stretch out fully in the bunks. Where our wood-burning stove stands today, right next to the mast, their feet dangled out of the bunks and hung in the air.

The fact that Gisel is not a man of extensive modernisation and repairs was "Wanderer's" - and our - good fortune. He preferred to devote himself to the details. He was able to fully immerse himself in carving small things such as the pockwood handles of our winch cranks or cleats; and Laurent Giles' logo was screwed to the bulwark with not seven, but 27 bronze screws. All these things are still with us; only his perfect paintwork has not remained.

Lost and living memories

Sitting with Gisel in his Mallorcan orange grove, it was now me, not him, who was interested in the details. Instead of German brown bread we had olives, instead of tea we had wine, while Kicki and I listened to his stories for days on end. In August 1975, for example, he replaced all the galvanised pontoons and the bow and stern pulpit with stainless steel ones at the renowned Goudy & Stevens boatyard in East Boothbay, Maine. And the stainless 1x19 forestay, whose skilful splicing I had admired for many years? He had it made simply because it was feasible. And what about that sketch of a freighter at 96º W on the chart? I don't know, he couldn't remember it. "But," he sank into thought, "the passage to the Marquesas was pure magic."

Just like for us.

Our first trip to the Pacific was the fourth for "Wanderer III"; and her third between the Galapagos Islands and the Marquesas. She steered herself, the sheets required almost no corrections - it was like a repeat of the Hiscocks' perfect sailing day on Friday the 13th in 1953.

On my map - Gisel's old one - two lines with very evenly spaced crosses ran parallel to the equator from the Galapagos Islands to the west. They marked Gisel's and Chantal's course and now ours. Each new cross drawn daily for our midday position stuck close to one of Gisel's and Chantal's; our westbound marks were almost the same.

Race on the nautical chart

On the spur of the moment, more out of curiosity, I plotted the daily positions of Eric and Susan's trips, and suddenly the journey became a race, sailed in the same boat but in different decades - by the Hiscocks in 1953, by Gisel and Chantal in 1976, and by us in 1991. Sometimes we were in the lead, sometimes one of them - until finally, 300 miles off Nuku Hiva, we were hopelessly stuck in a lull. Even when the wind returned, we were soon to fall further behind - due to a slowdown of a completely different kind.

Like hardly any other boat, "Wanderer III" has characterised the pattern of classic circumnavigations. You leave your home harbour, sail around the world in a rapid succession of passages along the trade wind route, touching one place on the way to the next and returning within a predetermined period of time. This is typically around three years. Both the Hiscocks and Gisel and Chantal followed this pattern. And, up to a point, so do we in the broadest sense.

The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway

My illness with hepatitis B then changed a lot of things. I fell ill on an uninhabited Tuamotu atoll called Motutunga. We were alone, with no means of communication, nobody knew where we were. Weakened by the hepatitis, it was impossible to leave the atoll. It was too beautiful for that. It held me physically, but also metaphysically captive - the tonal balance of the constant trade winds over my bunk was hallucinatory. Looking back at Motutunga, I realise that it is right here, in my tenth year on Wanderer, that we really merged into something completely separate; into her third story - the one with us and ours with her.

My hepatitis triggered something that made us break with the traditional Hiscock continuum - from Panama to New Zealand in one season. In the early 1990s, as a foreign yacht in French Polynesia, you needed a valid reason to be allowed to stay there during the cyclone season. When we arrived, still clearly weakened, I met the criteria. But six months non-stop in Tahiti or even on Moorea were not very appealing. As soon as I was halfway back in trim, we sailed northwards to the Kiribati Line archipelago on the equator during the cyclone season.

Once there, we stayed - and all plans fizzled out. The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway - the standard trade wind route around the world - and the remnants of a schedule-orientated impatience in me - they dissolved and disappeared. We had sailed into the slow-beating heart of the Pacific. Without my hepatitis, we would probably have continued the journey to my Samoan family and on to New Zealand. Instead, we were now fully absorbing the slowness of the Pacific and its inhabitants; we were in an ocean full of time. This experience set the standard for all our subsequent voyages in the Pacific, the Indian Ocean and later in the Southern Ocean.

From a yacht sailing around the world, it became a platform for being in this world

It also had a significant impact on my perception of "Wanderer" itself and the meaning it had for me. All yachting narcissism was overcome because of its insignificance. From a yacht travelling around the world, she became a fantastic platform to be in this world.

Before I left Europe on "Wanderer III" in 1987, I was still harbouring the idea of building a larger wooden boat myself after my return, one in the style of Laurent Giles' "Dyarchy", traditionally planked. The idea was to sail it hard after completion, set course for Chile, caulk the hull again and then coat it with copper where copper should be cheap. The second part of my idea revealed glaring gaps in my understanding of macroeconomics.

In 2000 in Chile, nine years after the decelerating diversions to the Line Islands, we had long realised that the only copper-plated boat we would ever own would be "Wanderer III". Because of her character, her simplicity, her small size and aesthetics, because of what she allows us to do, and because of her nature to be perfect for all her imperfections. Grow - yes, but not in size. If you accept the challenge of being satisfied in the small and simple, then there is hardly a better boat.

A whole range of adjectives for 96º W

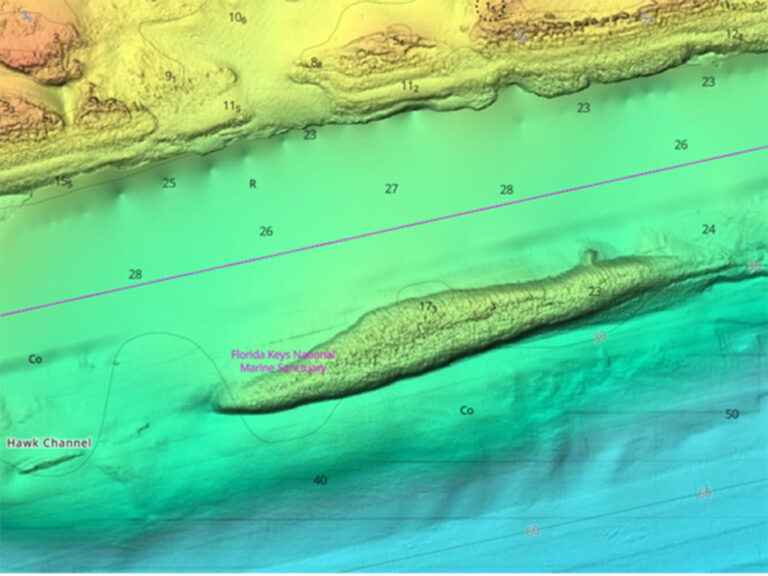

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, after two years in the Falklands and South Georgia, we had just painstakingly cruised northwards through Chile's Patagonian channels. Despite a few broken frames and colossal blows in the Southern Ocean, she had never leaked. We wanted to keep it that way and intended to carry out preventive repairs in New Zealand. With this in mind, we set sail from Puerto Montt, Chile, into the Pacific for our fifth encounter with 96º W.

The four previous meetings, all via Panama, had either been "magical" - Gisel's and ours - or "a bit too rough" - the Hiscocks'. This time, "Wanderer III" was turning on her own axis; we were drifting in the doldrums. Under a seemingly endless grey sky, a constant breeze had kept us going for several hundred miles west of Chile's coast on a north-westerly course to latitude 17º 30' south. But then, on the 22nd day at sea, we slid onto a magnet. At least that's what it felt like. Everything stopped suddenly, almost seamlessly: the wind, our movement, even the grey of the sky. It was as if we had sailed into the middle of a still, unchanging dreamscape.

"For the first time, overwhelming farsightedness, clearly contoured, with sharply drawn mountain ranges nothing more than unexplored cloudscapes, dream islands in the distance - reality and dream interpretation indistinguishable from nothing," I wrote in the logbook on 7 August 2000. All that remained for us was to drift powerlessly. If it was the 96º W's sole intention to invent days completely detached from human ambitions and to let us recognise them through "Wanderer", then it succeeded.

Course to New Zealand for restoration

The calm only lasted four days, but it gave barnacles a chance to take over the underwater hull. This in turn extended our passage to Penrhyn in the Cook Islands to 54 days. From there we sailed to New Zealand and put "Wanderer III" ashore for her half-century facelift. Quiet days were rare from then on. Every single day for well over a year was dedicated to her restoration.

It was here in New Zealand, after the Hiscocks had sold everything in England in 1974 and had become homeless sea nomads on their new steel ketch "Wanderer IV", that they received a letter from Bill Tilman. Tilman was another sailing icon of the time and had been the first to sail the high Arctic and Antarctic latitudes on various Bristol Pilot cutters - most famously his "Mischief". "I am not surprised," he writes to Eric and Susan, "that you are at a loss for new destinations for your next sailing voyages, as you have explored almost every corner of the globe. With the exception of where you are now, the only peaceful areas left are those that are still uninhabited by humans."

Declared goal: "Wanderer III" should not need a slipway for many years to come

If this was his sentiment almost half a century ago, how much more does it resonate in our reality today. Tilman's places of unpeopled nature have long attracted us. We intended to spend long periods in the Ultima Thules of our Earth, where repair is either difficult or non-existent. I wanted Wanderer III to require no structural intervention or even a slipway for many years. I was convinced that, although small and made of wood, she could survive in the rugged high latitudes into old age due to her original construction standard and the longevity built into her. Ultimately, these gifts also form the backbone of each of her eight 96º W crosses. They are the reason for her dry bilge.

Their longevity is based on a triptych of factors. First and foremost, the combination of owner, boat designer and boat builder. Eric Hiscock knew exactly what he wanted in 1952, Laurent Giles was an internationally renowned yacht designer, and William King's shipyard in Burnham-on-Crouch delivered the best quality in the country. The boat builders used carefully selected and dried wood, and the wood joints were perfect.

The second element of the triptych is the construction. The slender Karweel hull has very narrow Kalfat seams, an elm keel, elastic Sitka spruce fore-and-aft strakes, sterns, deadwood and deck beams made of grown oak - and not a drop of glue. The dimensions of all hull parts subject to particular loads, especially in the bilge, are oversized. The same applies to her hardwood panelling made of iroko. And then there are her metal connections; today they are almost exclusively made of copper. For a wooden boat, copper is almost like a source of eternal youth; all originally galvanised iron has been eliminated from the hull. And where copper is too soft to be used, as in the ballast keel bolts or metal floor cradles, aluminium-nickel-bronze is now used.

"Wanderer III" literally beckons to be groomed

But even this lifetime's advance of an exceptionally well thought-out design would not necessarily have been enough to allow her to sail more than 300,000 nautical miles in all the world's oceans without any problems if it were not for her three owners: Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and me. We filled her with voyages, we all lived on her, we admired her dearly - still do. It's not too big, on the contrary: it's small, pretty and harmonious. She literally beckons you to look after her. This is at least as important for its longevity as every structural detail. And, of course, like luck.

In 2003, on the very first voyage after the restoration of "Wanderer III" in New Zealand, we ended up on a reef in New Caledonia. Thanks to her new frames, her new copper plating, another repair and that all-important dose of luck, we were able to return to sailing. She survived a demanding test trip to Tasmania and on to New Zealand's sub-Antarctic islands without any leaks, giving us back the confidence we needed in her.

At the end of April 2005, at the beginning of the southern winter, we set off on a 71-day passage into the Southern Ocean from Dunedin, New Zealand, back to Chile. On the 59th day, we reached a position where God was playing chess with the surrounding highs and lows, but had obviously fallen asleep. Because without the slightest hint of change, it had been blowing at 9 to 10 Beaufort for days. We were lying at 39º S in a five-day storm. Five long days that we drifted back across longitude 96º W. Nevertheless, two characteristics of "Wanderers" that modern yachts no longer possess provided us with welcome comfort during these days: firstly, their ability to lie safely at anchor and secondly, the soothing muffling of the external howling in their cabin.

Double turning as relief valve

She turns unusually well, even under trysail alone. The ten-tonne weight of her hull in combination with her long lateral plan reduces her drift; above all, this makes it possible for her to sail upwind from a lee shore even at 40 knots under sail. This is an absolutely essential quality for a small, lightly motorised yacht like "Wanderer III", especially along the coasts in the high latitudes. It is the main reason why she can be sailed in these regions at all.

Once we had turned it round, it felt as if we had activated a relief valve, released the pressure and entered a state of alert slumber. When we closed the hatch and slipped down into the cabin, the over-excited howling outside lost its bite.

It is below deck, especially in storms, that the sound of a boat either encourages confidence or releases nerves. "Wanderer's" soothing sound kept all tension and irritability under control.

Sixth and seventh rendezvous

Something else, however, was worrying us. Our little Sony receiver had issued a rather absurd message: "Warning of falling spacecraft elements on 16 June 2005, between 0100 and 2300 UTC within the coordinates ..."

Exactly where we were. "What else are they going to throw at us?" shouted Kicki. But at some point, our chess-playing god made a move and allowed "Wanderer" to leave their lonely longitude behind for the sixth time.

The seventh rendezvous followed on New Year's Day 2006 at 25º 30' south - and was the diametric opposite of the sixth. Just as lengthy and awkward, only this time with absolutely no noise and zero wind - courtesy of the expanding Easter Island High. Compared to that five-day crossing, the two days we spent stuck on the line seemed like a hasty pit stop.

Turning point at 96º W

Whenever "Wanderer" encountered 96º W so far, she had left all signs of human activity behind her. That changed now. What I observed from the deck was more unsettling than any storm. I leaned my upper body over the railing and stared vertically into the sea to a point where the sun's rays converged concentrically in the deep blue. At some point, I focussed my gaze on tiny particles floating in the upper part of the sea column. Plankton. Or so it seemed.

I grabbed a bucket, dipped it in the sea and ... fished out fibres. What appeared to be plankton were actually plastic particles. The deep blue upper layer of the sea was strewn with a loosely woven carpet of the tiniest particles of our civilisation's rubbish. Everywhere I looked, I discovered plankton-like fluff and shreds, ejected by the achievements of a buzzing world somewhere else. This was not the densely populated North Pacific with its famous rubbish vortex, but a place far from human centres. This was where Thor Heyerdahl sailed through an almost untouched ocean with his "Kon-Tiki" in 1947. And where, a few years later, "Wanderer III" showed many of us our course for the first time.

At the beginning of the 1950s, the oceans were still unspoilt in their diversity of life. This is the time when "Wanderer's" story begins, around the same time as the ecologically precarious acceleration of consumer behaviour in our society. Since then, practically all our activities have flowed in one way or another into the sea that stores our excesses. Below deck, amidst its unchanged furnishings from another era, "Wanderer" may seem like a time machine. But on deck, surrounded by the sea, I think of her as a contemporary witness. Because she has witnessed the evolution of our current ecological dilemma from her well-travelled vantage point from the very beginning. For us, she is the ideal partner to peel back all these layers of the diversity of life - in beauty as well as in sorrow.

I realised that I could only see the carpet of plastic fluff when it was calm. As soon as it breaks up, it tears, escapes the eye and the sea surface shines and sparkles. Movement transcends so many things, including pollution.

Change and the future

I would certainly not have understood all this if we had hurried on this journey and not drifted windlessly. "Wanderer III" will never have a large engine, never carry much diesel. A large double berth is also out of the question. Like Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and I have learnt to live well with their spatial and temporal limitations. They suit us, we see them as an asset, we simply give them a lot of time and as a result we see other things and many things differently than if we did not.

Until recently, longitude 96º W was not so easy to reach from the Falkland Islands due to Covid, unless it was upwind around Cape Horn. This restriction also required time, patience, as perhaps the entire view of "Wanderer's" era required a moist eye that keeps up with the times. How much will have changed when she next finds herself with us at 96º W?

It will be wet, quiet, windless or stormy and - as always - no place to stay. But - I hope - its remoteness can still be felt, even in me.

Also interesting:

- Spectacular find in the Antarctic: researchers discover the wreck of Shackleton's "Endurance"

- Forgotten history: How a Bavarian builds a sailing boat and sails to India

- Portrait: Georg Dibbern makes history in German sailing

Most read in category Special

From his childhood, Thies Matzen had dreamed of becoming a wooden boat builder, and was enthralled with Eric & Susan Hiscock's Wanderer III and her voyages. As a young man, he was able to purchase Wanderer III and restore her to better than original condition while maintaining her classic rig and features. For 25 years, Thies Matzen and Kicki Ericson have sailed more than 135,000 nautical miles aboard Eric and Susan Hiscock's iconic 30 footer. Here is their story about Wanderer III.

Weather Forecast

2:00 pm, 06/12: -11°C - Partly Cloudy

2:00 am, 07/12: -4°C - Clear

2:00 pm, 07/12: -7°C - Partly Cloudy

2:00 am, 08/12: -3°C - Overcast

- Cruising Compass

- Multihulls Today

- Advertising & Rates

- Author Guidelines

British Builder Southerly Yachts Saved by New Owners

Introducing the New Twin-Keel, Deck Saloon Sirius 40DS

New 2024 Bavaria C50 Tour with Yacht Broker Ian Van Tuyl

Annapolis Sailboat Show 2023: 19 New Multihulls Previewed

2023 Newport International Boat Show Starts Today

Notes From the Annapolis Sailboat Show 2022

Energy Afloat: Lithium, Solar and Wind Are the Perfect Combination

Anatomy of a Tragedy at Sea

What if a Sailboat Hits a Whale?!?

Update on the Bitter End Yacht Club, Virgin Gorda, BVI

Charter in Puerto Rico. Enjoy Amazing Food, Music and Culture

With Charter Season Ahead, What’s Up in the BVI?

AIS Mystery: Ships Displaced and Strangely Circling

Holiday Sales. Garmin Marine Stuff up to 20% Off

- Cruising News

Great Voyages in Small Boats

BWS takes a look back at some of the famous, notable and most influential small boat cruies of all time…and many are Americans (published July 2014)

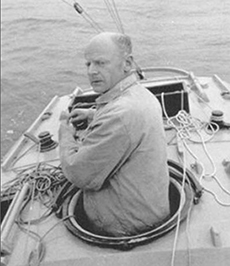

You could say that the modern age of shorthanded and solo offshore sailing and circumnavigations came of age in the early 1960s with the first running of the Observer Singlehanded Transatlantic Race (OSTAR) from England to Newport, RI, an event that was won by Sir Francis Chichester.

Yet it was Blondie Hasler, one of the event’s founders, who made real waves by competing in a 26-foot folkboat named Jester , on which he had installed a simple to handle junk rig and he carried his ingenious invention, the Hasler windvane self steering gear. That simple invention changed the way we modern sailors go to sea.

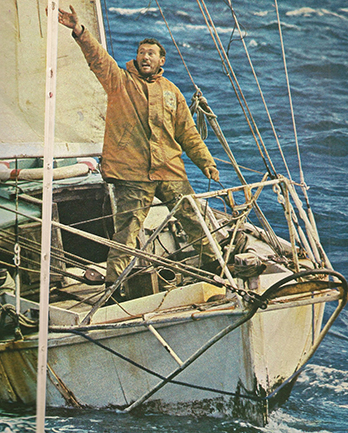

Eight years after the first OSTAR, the Sunday Times newspaper in the U.K. launched the Golden Globe Race, which was the first singlehanded non-stop around the world race. It was sailed by the four great capes: Cape of Good Hope, Cape Leeuwin, South Cape and Cape Horn—all made famous by the clipper ships of yore.

Almost all of the boats that completed the event carried self-steering devices on their sterns. And some carried rudimentary mechanical autopilots and early roller furling headsail devices. Technology was evolving to make life offshore easier, safer and better for solo and shorthanded crews.

This first round the world race was joined by a fleet of most unusual gentlemen and created legends that survive today. It was the race in which we first met Sir Robin Knox-Johnson who won the event in the smallest and slowest boat, his 32-foot Suhali , but managed to finish in the shortest elapsed time. Knox-Johnson’s sailing career has spanned the decades and he has held records and trophies in all offshore genres. Today, Knox-Johnson is the founder and Executive Chairman of the Clipper Round the World Race that visited New York in June 2014.

Among the sailors in the first Golden Globe was Bernard Moitessier who abandoned the race at Cape Horn to sail on to Tahiti to “save his soul.” There were British paratroopers Bill King and Chay Blyth, neither of whom finished; but Blyth would go on to become one of Britain’s most illustrious offshore sailors. There was Nigel Tetley in a trimaran whose boat broke up not far from the finish line; poor Tetley was later found hanged in his closet dressed in women’s clothes.

And, the most infamous member of this gallery was Donald Crowhurst who set off late in the race in an ill prepared trimaran and preceded to file counterfeit position reports by radio as he secretly drifted around the South Atlantic. Crowhurst’s fraudulent track around the world was going to be the fastest and he was determined to finish first. But his mind gave out, he could not complete the fraud and his tri, T eignmouth Electron , was found adrift with her skipper missing.

Knox-Johnson became an international hero. Crowhurst became the anti-hero of a cautionary tale of ambition gone wrong at sea. And the Golden Globe became a model for the shorthand offshore races that would follow. These events have become the proving grounds for yacht design and yacht equipment that would shape small boat voyaging in the modern age. And from that era, the picture of little Jester sailing into Newport harbor with Blondie Hasler peering around from his hatch while his easy to handle junk rig drove her forward and servo-pendulum windvane gear ably steered the boat, is the first real picture of the modern age of small boat voyaging.

EARLY SMALL BOAT VOYAGES But men had been going to sea in small boats long before Hasler, Chichester and Knox-Johnson. It is interesting that Americans led the way in the world of small boat voyaging. For most of us, Joshua Slocum’s solo circumnavigation in the 1890s, made famous in his book Sailing Alone Around the World , marks the start of the age of voyaging under sail in small boats. Certainly, Slocum’s cruise west about from New Bedford, Massachusetts via Cape Horn, the Torres Straits and the Cape of Good Hope, which totaled 46,000 miles, was a magnificent feat of seamanship and small boat navigation. At 36 feet, Spray was no bigger than many ship’s lifeboats or gigs and was considered very small for such a voyage at the time.

Slocum’s book became a best seller and his lectures across America were given to huge, amazed crowds. One man was inspired by Slocum to try his hand at small boat voyaging. John Voss of Victoria, B.C., Canada, who was an experienced sailor, fitted out a 30-foot Native American war canoe and sailed it singledhanded from Victoria to London, England via the Torres Straits and the Cape of Good Hope. Like Slocum, Voss earned his way by giving lectures and eventually wrote the excellent book T he Venturesome Voyages of Captain Voss .

Slocum inspired many Americans to follow in his wake and Voss did the same for many Europeans and, surprisingly, the Japanese. In America, the founder of The Rudder magazine (1890), Thomas Fleming Day, was already a force in the offshore sailing community along the East Coast and through his magazine did much to promote the Slocum and Voss voyages. To prove his critics wrong about the dangers of sea voyages in small boats, in 1906 Day founded the New York to Bermuda Race, which he won. The race has been run ever since, and in 2014 the 49th Race to the Onion Patch departed in June.

Day was also a yacht designer and to prove that small boats could be sailed across the Atlantic Ocean, he designed and built the 25-foot yawl Sea Bird in which he and two friends sailed from New York to England. The feat opened the door for hundreds of Americans to discover the cruising and voyaging life in small, inexpensive boats and may have been instrumental in building a new enthusiasm for recreational sailing across America.

One such enthusiast was Harry Pidgeon, an adventurer and noted photographer. In 1917 he discovered in The Rudder Day’s plans for a 38-foot version of Sea Bird . Pidgeon copied the plans and built Islander , which he rigged as a yawl. In 1921, he set off from California to become the second person to sail alone around the world and the first to do so via the Panama Canal. His voyage took four years and was made famous through The Rudder and in Pidgeon’s book Around the World Single-Handed .

In 1932, Pidgeon embarked on a second solo circumnavigation aboard Islander that lasted five years. Prior to building Islander , he had never been to sea and was in no way a sailor. Yet, he thrived on the life and was able to collect thousands of photographs that form a valuable ethnographic record of remote regions and native populations of the world at that time. His photos are in the Cabrillo Museum in Los Angeles.

While Americans might have pioneered the realms of small boat voyaging, today the French, and Europeans in general, dominate the shorthanded and small boat racing and cruising fleets. In France, sailing is on par with baseball in America and skippers are known in the general public by their first names. So it is worth noting the first Frenchman who had a burning desire to sail the oceans in a small cruising boat and discover the world on his own terms.

In the 1890s, Alain Gerbault was born to a well to do family in Brittany where he learned to sail on his father’s yacht and learned the ways of the sea from the local fishermen. He was a smart, shy boy who was gifted with languages and was an expert lawn tennis player. After World War I, in which he flew fighter planes, his dream of seafaring led him to buy the British- built sloop and in 1923 he departed France for a solo voyage to America. The transatlantic passage was a disaster and he nearly lost both his life and . Plus, he found the need to steer the boat exhausting to the point of collapse. Yet, he prevailed and was greeted in New York as an adventurous hero. As it happened, he arrived in New York in time to play in the U.S. Tennis Open. He didn’t win.

There were may other less heralded but still intrepid shorthanded small boat voyages from the decades before World War II, such as American Edward Miles, who sailed his 34 foot sturdy sloop on the first east about circumnavigation via Suez and Panama. Yet, it was only after World War II that the numbers of sailors ready, willing and able to set off on small boat voyages grew from a trickle to a flood.

MODERN SMALL BOAT VOYAGES After the war, as Europe put itself back together and the rest of the western world become increasingly prosperous, people had more time and money to take up lifestyles like the cruising life. A sailing industry was beginning to form and fiberglass was making boats easier to build, stronger and more adaptable to modern design innovations that eluded builders of wood boats.

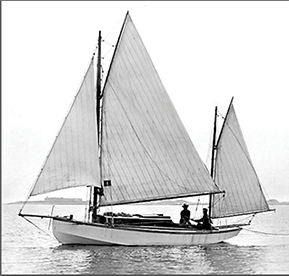

Yet, in the 1950s, wood boats were still the norm and one, in particular, Wanderer III , was destined to be a paradigm of the modern couple’s small cruising boat. She was a 30-foot Laurent Giles design, carvel planed on oak frames with a simple sloop rig with hanked on headsails and round-the-boom roller furling on the mainsail. She had a cruising full keel with a cutaway forefoot and an attached rudder.

She was owned by the British couple Susan and Eric Hiscock who were experienced coastal and offshore sailors, most notably cruising in and around the British Isles. Aboard their new Wanderer III , the Hiscocks set off from England in 1952 and headed west with the sun on a three-year circumnavigation via Panama, the Torres Straits and Cape of Good Hope. Their voyage was a model of prudent, modern voyaging along the trade wind routes. The Hiscocks were great planners, were careful in their preparation and always practiced prudent seamanship. The book that followed the circumnavigation, Wanderer III Around the World , is not only a fine cruising yarn, it is also by example a terrific primer on how to do it right.

The Hiscocks would go on to make two more circumnavigations and build two new Wanderer s along the way. Yet, the small boat voyage in their 30-foot Wanderer III may have been the best of all.

Not only were the Hiscocks competent voyaging sailors, they were also good writers and eager to pass on the knowledge they learned over the miles. Hiscock’s books Cruising Under Sail and Voyaging Under Sail (now combined into one volume called Cruising Under Sail ) are the early essential guides to buying, fitting out and preparing for blue water sailing. They are dated by today’s standards, yet they still contain kernels of wisdom that often are missing in today’s tomes. They are books that certainly launched thousands of cruising dreams.

In the 1950s, the English couple Myles and Beryl Smeeton had retired from mountain climbing and taken to the sea aboard a 43-foot ketch named Tzu Hang . They were an intrepid couple and made adventurous voyages all over the world. Myles later wrote several wonderful books about their adventures including the tale of pitchpoling off Cape Horn. Certainly, the Smeetons were early pathfinders for cruisers who would follow. On that voyage to Cape Horn, chronicled in Once is Enough , the Smeetons had with them a young Englishman named John Guzzwell who was both a fine young sailor and an accomplished boatwright. It was a good thing he was along. When Tzu Hang pitchpoled, she lost her rig and had the wood hatches torn from the deck. It was Guzzwell who put her back together again, carefully, expertly so she could sail back into Valparaiso, Chile 68 days later with all souls aboard safe.

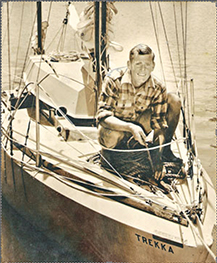

Guzzwell had met the crew of Tzu Hang in Hawaii where he was cruising aboard the 21-fot Laurent Giles sloop Trekka that he had built in British Columbia. The two boats cruised in company for several months and finally, in New Zealand John decided to store Trekka for a time so he could sail with Miles and Beryl around Cape Horn. The rest was history. Guzzwell left Tzu Hang in Chile and traveled back to New Zealand were he launched Trekka and carried on around the world. He returned to B.C. in 1959, having completed a singlehanded circumnavigation in the smallest boat on record.

During the fifties, dozens of sailors made small boat voyages that expanded the cruising horizons and helped evolve the design and rigging of modern cruisers. If the Hiscocks and Smeetons were the marquee cruisers of that decade then Robin Lee Graham was the name in lights in the sixties. In 1965, as a brash young teenager of 16, Graham singlehanded a 24-foot fiberglass Lapworth sloop, Dove , from California to Hawaii and along the way hatched a plan to become the youngest person to sail solo around the globe. Surprisingly, his parents went along with scheme. Even more surprisingly, National Geographic magazine agreed to carry installments from Graham along the way.

Graham departed Hawaii in September 1965 and cruised south and west to the islands of the South Pacific. He cruised and explored the islands and met the natives, and by the time he was 17, he had a year of blue water sailing and cruising under his keel and he was on his way west toward Australia and Southeast Asia. But he was still just a guy out there living the dream.

That all ended in October 1968 when the first installment of his cruise appeared in a full feature in National Geographic. In those days, the Geographic had one of the largest readerships of any magazine and it was truly worldwide. Something happened. Graham’s story struck a chord in the Baby Boom Generation like almost nothing else, whether the readers were sailors or not. Here was a young man who had stepped off the merry-go-round and headed off to see the world aboard his own sailboat. In the following two years, Graham published two more stories in the Geographic and in the process became a celebrity, something he had neither sought nor wanted. But there it was.

He returned to California in 1970 to a celebrity’s welcome. Ford gave him a brand new Mustang. Book publishers buried him in proposals and contracts. TV crews wanted sound bites. Graham tried to reintegrate himself into the world but couldn’t. He sold the Mustang, bought a hippy van and headed to the solitude of the Montana mountains where he and his wife Patti built a log home and raised their two children. But he had left his mark. Thousands upon thousands of young dreamers got the bug to go cruising and, not surprising for the Baby Boomers, many of them did. His book recounting the voyage, Dove, became an international best seller and continues to sell well to this day.

“Go Simple. Go small. Go now.” That is the mantra of all small boat voyagers today as it has been for nearly 40 years since it was first coined by Lin and Larry Pardey. Today, after two circumnavigations, more than 170,000 sea miles, 11 books, five DVDs and hundreds of magazine articles and lectures, the couple has become the face of cruising in America and around the world. Yet, when they started out in 1968 aboard the 24-foot Lyle Hess-designed Seraffyn , which Larry built with his own hands, they were just two free spirited adventurers with a passion for the sea.

For the next 11 years, they wound their way east about the world from California to Europe via Panama, then Europe to Asia via Suez and finally back to California in 1979. Along the way and after their return, they wrote the now classic cruising books Cruising in Seraffyn, Seraffyn’s European Adventure, Seraffyn’s Mediterranean Adventure and Seraffyn’s Oriental Adventure .

After all those years living cheek to jowl aboard their 24-footer, the Pardey’s needed a bigger boat. They had asked Lyle Hess to design it for them and in the early 1980s they moved ashore into the hills of California so Larry could build Taleisin , their new 30-footer. The story of their years ashore is told in the highly regarded memoir Lin wrote called Bull Canyon .

Taleisin was launched in 1984 and soon the Pardeys were at sea again and on their way around the world, this time west about by the southern route via New Zealand, southern Australia, the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. This voyage lasted the better part of 16 years, with side cruises to the East Coast of the U.S., England, the West Coast and British Columbia. They cruised the world and went where the wind and their endless curiosity took them until they finally came to roost in New Zealand, which is now their home.

The Pardeys, who built their own boats, never sailed with an inboard engine, eschewed modern electronics, and stayed true to ancient traditions of the sea, and have always had their followers and detractors. Yet, they are quintessential cruisers and have inspired tens of thousands of sailors to go simple, go small and go now.

In the annals of small boat voyaging, Tania Aebi’s cruise around the world from May 1985 to November 1987 ranks as one of the gutsiest. At the ripe old age of 18, she set off from her home in New York City aboard the 26-foot sloop Varuna bound for Bermuda and then the Panama Canal. An indifferent student with a wanderlust, she had persuaded her father to fund her voyage instead of paying for college on the condition that she complete a circumnavigation and then write a book about it. But first she had to learn to sail and navigate.

Her first passage to Bermuda should have taken six days. Without a long range HF radio she could not report her position as she sailed southeast nor could she ask for help with her celestial calculations. After eight days, friends and family began to worry and after 10 there was real concern until she finally called in from a phone booth in St. George’s, Bermuda to report a safe landfall. As it turned out, she had missed the island on her first pass by 80 miles and only realized her mistake when she was well out into the Atlantic. Using a handheld RDF she located Bermuda Radio and was able to home in on its signal until she was home and dry.

The voyage and Tania’s skills improved with each landfall as she sailed to Panama and then on across the South Pacific by the trade wind route. Gregarious and full of fun, she made friends wherever she sailed and impressed other cruisers with her pluck and courage. Her mission was to become the youngest person and first American woman to sail solo around the world. No small task. But life has a way of interrupting plans. In Vanuatu, Tania met a young French singlehander named Olivier and fell in love. From there onward, they sailed in tandem, Varuna and Oliver’s black ketch Akka , over the top of Australia, through Indonesia, across the Indian Ocean and up the Red Sea. They were inseparable but still sailing solo.

In Malta, Tania’s mission came into clear focus. If she dallied for the next winter she would lose her chance to break the records she had in her sights. If she left, she would be leaving Olivier behind because he was not planning to cross the Atlantic again. So she set off alone and lonely to make the passage to Gibraltar and then straight across the Atlantic to New York in the weather window between the hurricane season and the onset of winter gales.

She arrived in New York on November 6, 1987 and was greeted at New York’s South Street Seaport by a huge crowd and the international press. She had done it. And even better, Olivier surprised her by being there to welcome her home. Her book, Maiden Voyage , written with Cruising World magazine’s then Deputy Editor Bernadette Brennan (now Bernon), became a best seller and Tania’s tale, like Robin Lee Graham’s, has become an inspiration for young sailors around the world.

While not as famous as some of the small boat voyagers who have sailed solo around the world, Donna Lang is one sailor whose tale is also an inspiration for women and all sailors who want to just go out there and do it. After a personal tragedy disrupted her life, Donna, who is a professional musician, went to sea as a cook on a tall ship. She fell in love with the sea and forged in her mind the idea that a solo trip around the world, with only one stop, would be the only thing that would lead her back to the personal peace that she had lost.

With almost no money, she managed to buy a Southern Cross 28, Inspired Insanity , and fit it out with the essential gear needed for safe passagemaking. She made a solo trip from Bristol, RI to the Virgin Islands and with that trial voyage under her belt set off for the 168-day voyage around the Cape of Good Hope to New Zealand. Along the way she met every type of weather from calms to repeated southern ocean gales. Her little boat was often overwhelmed by huge seas and had to lie to a sea anchor. Yet, she made it and was welcomed in New Zealand warmly. She spent months in New Zealand refitting her boat and then set off for the nonstop passage around Cape Horn and on to Rhode Island. Off the Horn she was near a yacht that was dismasted and needed assistance. While other cruisers came to the rescue, Donna managed communications via her sat phone and was able to facilitate the rescue of the other boat and crew. Although she had not planned to stop, she diverted to Puerto Williams in Chile to finalize the rescue and meet her new friends.

From Chile, she sailed north and was just days from Rhode Island when she met a huge spring gale that forced her first to heave to and then ultimately to retreat to Bermuda. She had closed the circle for the circumnavigation and in the process, had inspired many ashore while finding in herself the new sense of well being and peace that tragedy swept away.

The final small boat voyage that needs to be part of this compendium belongs to Matt Rutherford of Annapolis, Maryland. Like most voyagers, Matt had a mission and set out to fulfill it by sailing alone around the Americas via the Northwest Passage and a rounding of Cape Horn.

Already an experienced solo sailor with an Atlantic circle under his belt, Matt conceived of the voyage around the Americas as a way to test himself while raising money for CRAB (Chesapeake Region Accessible Boating), which provides access to sailing for the handicapped. Rutherford had had a very rough start in life and had been on a path toward prison as a teenager. He had fought his way free from that life with some help from others and had come to deeply understand how important giving back to society is to becoming a whole man.

Rutherford undertook the voyage between June 2011 and April 2012 and sailed in a borrowed Vega 27 named St. Brendan with a Monitor windvane on the stern. His solo trip through the Northwest Passage was not the first, but it was accomplished with steady competency and sound seamanship. The nearly pole to pole voyage down the length of the Pacific Ocean was no small feat in itself, yet he made it sound like a pleasant cruise in his regular blogs. Rounding the Horn was a huge milestone and the last real turning mark of the course. He made it without too much fuss or bother. Matt’s that kind of sailor.

But the boat and its system were suffering from the strain of the voyage so he was forced to heave to off Recife, Brazil so friends could restock him with supplies and gear. Ten months after departing the Chesapeake Bay, Matt sailed under the Bay Bridge and then on to Annapolis, Maryland. He had raised more then $130,000 in donations for CRAB and had sailed himself into the form of a full-fledged man.

EPILOGUE Small boat voyaging is not for everyone nor is solo or shorthanded sailing. Yet, it is always a pleasant surprise for those of us who cruise in larger boats—most cruisers, especially couples, are sailing 40-footers or larger these days—to sail into a far flung anchorage and find three or more small boats under 30 feet that have crossed oceans and arrived safely and almost always on a very limited budget. What the famous small boat sailors teach us over and over is that it is not necessarily about the size of the boat, it is about the size of the dream.

Author: George Day

Yachting Monthly

- Digital edition

25 of the best small sailing boat designs

- Nic Compton

- August 10, 2022

Nic Compton looks at the 25 yachts under 40ft which have had the biggest impact on UK sailing

There’s nothing like a list of best small sailing boat designs to get the blood pumping.

Everyone has their favourites, and everyone has their pet hates.

This is my list of the 25 best small sailing boat designs, honed down from the list of 55 yachts I started with.

I’ve tried to be objective and have included several boats I don’t particularly like but which have undeniably had an impact on sailing in the UK – and yes, it would be quite a different list if I was writing about another country.

If your favourite isn’t on the best small sailing boat designs list, then send an email to [email protected] to argue the case for your best-loved boat.

Ready? Take a deep breath…

Credit: Bob Aylott

Laurent Giles is best known for designing wholesome wooden cruising boats such as the Vertue and Wanderer III , yet his most successful design was the 26ft Centaur he designed for Westerly, of which a remarkable 2,444 were built between 1969 and 1980.

It might not be the prettiest boat on the water, but it sure packs a lot of accommodation.

The Westerly Centaur was one of the first production boats to be tank tested, so it sails surprisingly well too. Jack L Giles knew what he was doing.

Colin Archer

Credit: Nic Compton

Only 32 Colin Archer lifeboats were built during their designer’s lifetime, starting with Colin Archer in 1893 and finishing with Johan Bruusgaard in 1924.

Yet their reputation for safety spawned hundreds of copycat designs, the most famous of which was Sir Robin Knox-Johnston ’s Suhaili , which he sailed around the world singlehanded in 1968-9.

The term Colin Archer has become so generic it is often used to describe any double-ender – so beware!

Contessa 32

Assent ‘s performance in the 1979 Fastnet Race makes the Contessa 32 a worth entry in the 25 best small sailing boat designs list. Credit: Nic Compton

Designed by David Sadler as a bigger alternative to the popular Contessa 26, the Contessa 32 was built by Jeremy Rogers in Lymington from 1970.

The yacht’s credentials were established when Assent , the Contessa 32 owned by Willy Kerr and skippered by his son Alan, became the only yacht in her class to complete the deadly 1979 Fastnet Race .

When UK production ceased in 1983, more than 700 had been built, and another 20 have been built since 1996.

Cornish Crabber 24

It seemed a daft idea to build a gaff-rigged boat in 1974, just when everyone else had embraced the ‘modern’ Bermudan rig.

Yet the first Cornish Crabber 24, designed by Roger Dongray, tapped into a feeling that would grow and grow and eventually become a movement.

The 24 was followed in 1979 by the even more successful Shrimper 19 – now ubiquitous in almost every harbour in England – and the rest is history.

Drascombe Lugger

Credit: David Harding

There are faster, lighter and more comfortable boats than a Drascombe Lugger.

And yet, 57 years after John Watkinson designed the first ‘lugger’ (soon changed to gunter rig), more than 2,000 have been built and the design is still going strong.

More than any other boat, the Drascombe Lugger opened up dinghy cruising, exemplified by Ken Duxbury’s Greek voyages in the 1970s and Webb Chiles’s near-circumnavigation on Chidiock Tichbourne I and II .

The 26ft Eventide. Credit: David Harding

It’s been described as the Morris Minor of the boating world – except that the majority of the 1,000 Eventides built were lovingly assembled by their owners, not on a production line.

After you’d tested your skills building the Mirror dinghy, you could progress to building a yacht.

And at 24ft long, the Eventide packed a surprising amount of living space.

It was Maurice Griffiths’ most successful design and helped bring yachting to a wider audience.

You either love ’em or you hate ’em – motorsailers, that is.

The Fisher 30 was brought into production in 1971 and was one of the first out-and-out motorsailers.

With its long keel , heavy displacement and high bulwarks, it was intended to evoke the spirit of North Sea fishing boats.

It might not sail brilliantly but it provided an exceptional level of comfort for its size and it would look after you when things turned nasty.

Significantly, it was also fitted with a large engine.

Credit: Rupert Holmes

It should have been a disaster.

In 1941, when the Scandinavian Sailing Federation couldn’t choose a winner for their competition to design an affordable sailing boat, they gave six designs to naval architect Tord Sundén and asked him to combine the best features from each.

The result was a sweet-lined 25ft sloop which was very seaworthy and fast.

The design has been built in GRP since the 1970s and now numbers more than 4,000, with fleets all over the world.

Credit: Kevin Barber

There’s something disconcerting about a boat with two unstayed masts and no foresails, and certainly the Freedom range has its detractors.

Yet as Garry Hoyt proved, first with the Freedom 40, designed in collaboration with Halsey Herreshoff, and then the Freedom 33 , designed with Jay Paris, the boats are simple to sail (none of those clattering jib sheets every time you tack) and surprisingly fast – at least off the wind .

Other ‘cat ketch’ designs followed but the Freedoms developed their own cult following.

Hillyard 12-tonner

The old joke about Hillyards is that you won’t drown on one but you might starve to death getting there.

And yet this religious boatbuilder from Littlehampton built up to 800 yachts which travelled around the world – you can find them cruising far-flung destinations.

Sizes ranged from 2.5 to 20 tons, though the 9- and 12-ton are best for long cruises.

The innovations on Jester means she is one of the best small sailing boat designs in the last 100 years. Credit: Ewen Southby-Tailyour

Blondie Hasler was one of the great sailing innovators and Jester was his testing ground.

She was enclosed, carvel planked and had an unstayed junk rig.

Steering was via a windvane system Hasler created.

Hasler came second in the first OSTAR , proving small boats can achieve great things.

Moody kicked off the era of comfort-oriented boats with its very first design.

The Moody 33, designed by Angus Primrose, had a wide beam and high topside to produce a voluminous hull .

The centre cockpit allowed for an aft cabin, resulting in a 33-footer with two sleeping cabins – an almost unheard of concept in 1973 –full-beam heads and spacious galley.

What’s more, her performance under sail was more than adequate for cruising.

Finally, here was a yacht that all the family could enjoy.

Continues below…

What makes a boat seaworthy?

What characteristics make a yacht fit for purpose? Duncan Kent explores the meaning of 'seaworthy' and how hull design and…

How boat design is evolving

Will Bruton looks at the latest trends and innovations shaping the boats we sail

How keel type affects performance

James Jermain looks at the main keel types, their typical performance and the pros and cons of each

Boat handling: How to use your yacht’s hull shape to your advantage

Whether you have a long keel or twin keel rudders, there will be pros and cons when it comes to…

Nicholson 32

Credit: Genevieve Leaper

Charles Nicholson was a giant of the wooden boat era but one of his last designs – created with his son Peter – was a pioneering fibreglass boat that would become an enduring classic.

With its long keel and heavy displacement, the Nicholson 32 is in many ways a wooden boat built in fibreglass – and indeed the design was based on Nicholson’s South Coast One Design.

From 1966 to 1977, the ‘Nic 32’ went through 11 variations.

Credit: Hallberg-Rassy

In the beginning there was… the Rasmus 35. This was the first yacht built by the company that would become Hallberg-Rassy and which would eventually build more than 9,000 boats.

The Rasmus 35, designed by Olle Enderlein, was a conservative design, featuring a centre cockpit, long keel and well-appointed accommodation.

Some 760 boats were built between 1967 and 1978.

Credit: Larry & Lin Pardey

Lyle Hess was ahead of his time when he designed Renegade in 1949.

Despite winning the Newport to Ensenada race, the 25ft wooden cutter went largely unnoticed.

Hess had to build bridges for 15 years before Larry Pardey asked him to design the 24ft Seraffyn , closely based on Renegade ’s lines but with a Bermudan rig.

Pardey’s subsequent voyages around the world cemented Hess’s reputation and success of the Renegade design.

Would the Rustler 36 make it on your best small sailing boat list? Credit: Rustler Yachts

Six out of 18 entries for the 2018 Golden Globe Race (GGR) were Rustler 36s, with the top three places all going to Rustler 36 skippers.

It was a fantastic endorsement for a long-keel yacht designed by Holman & Pye 40 years before.

Expect to see more Rustler 36s in the 2022 edition of the GGR!

It was Ted Heath who first brought the S&S 34 to prominence with his boat Morning Cloud .

In 1969 the yacht won the Sydney to Hobart Race, despite being one of the smallest boats in the race.

Other epic S&S 34 voyages include the first ever single-handed double circumnavigation by Jon Sanders in 1981

Credit: Colin Work

The Contessa 32 might seem an impossible boat to improve upon, but that’s what her designer David Sadler attempted to do in 1979 with the launch of the Sadler 32 .

That was followed two years later by the Sadler 29 , a tidy little boat that managed to pack in six berths in a comfortable open-plan interior.

The boat was billed as ‘unsinkable’, with a double-skinned hull separated by closed cell foam buoyancy.

What’s more, it was fast, notching up to 12 knots.

Credit: Dick Durham/Yachting Monthly

Another modern take on the Contessa theme was the Sigma 33, designed by David Thomas in 1979.

A modern underwater body combined with greater beam and higher freeboard produced a faster boat with greater accommodation.

And, like the Contessa, the Sigma 33 earned its stripes at the 1979 Fastnet, when two of the boats survived to tell the tale.

A lively one-design fleet soon developed on the Solent which is still active to this day.

A replica of Joshua Slocum’s Spray . Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

The boat Joshua Slocum used for his first singlehanded circumnavigation of the world wasn’t intended to sail much further than the Chesapeake Bay.

The 37ft Spray was a rotten old oyster sloop which a friend gave him and which he had to spend 13 months fixing up.

Yet this boxy little tub, with its over-optimistic clipper bow, not only took Slocum safely around the world but has spawned dozens of modern copies that have undertaken long ocean passages.

Credit: James Wharram Designs

What are boats for if not for dreaming? And James Wharram had big dreams.

First he sailed across the Atlantic on the 23ft 6in catamaran Tangaroa .

He then built the 40ft Rongo on the beach in Trinidad (with a little help from French legend Bernard Moitessier) and sailed back to the UK.

Then he drew the 34ft Tangaroa (based on Rongo ) for others to follow in his wake and sold 500 plans in 10 years.

Credit: Graham Snook/Yachting Monthly

The Twister was designed in a hurry.

Kim Holman wanted a boat at short notice for the 1963 season and, having had some success with his Stella design (based on the Folkboat), he rushed out a ‘knockabout cruising boat for the summer with some racing for fun’.

The result was a Bermudan sloop that proved nigh on unbeatable on the East Anglian circuit.

It proved to be Holman’s most popular design with more than 200 built.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Laurent Giles’s design No15 was drawn in 1935 for a Guernsey solicitor who wanted ‘a boat that would spin on a sixpence and I could sail single-handed ’.

What the young Jack Giles gave him was a pretty transom-sterned cutter, with a nicely raked stem.

Despite being moderate in every way, the boat proved extremely able and was soon racking up long distances, including Humphrey Barton’s famous transatlantic crossing on Vertue XXXV in 1950.

Wanderer II and III

Credit: Thies Matzen

Eric and Susan Hiscock couldn’t afford a Vertue, so Laurent Giles designed a smaller, 21ft version for them which they named Wanderer II .

They were back a few years later, this time wanting a bigger version: the 30ft Wanderer III .

It was this boat they sailed around the world between 1952-55, writing articles and sailing books along the way.

In doing so, they introduced a whole generation of amateur sailors to the possibilities of long-distance cruising.

Westerly 22

The origins of Westerly Marine were incredibly modest.

Commander Denys Rayner started building plywood dinghies in the 1950s which morphed into a 22ft pocket cruiser called the Westcoaster.

Realising the potential of fibreglass, in 1963 he adapted the design to create the Westerly 22, an affordable cruising boat with bilge keels and a reverse sheer coachroof.

Some 332 boats were built to the design before it was relaunched as the Nomad (267 built).

Enjoyed reading 25 of the best small sailing boat designs?

A subscription to Yachting Monthly magazine costs around 40% less than the cover price .

Print and digital editions are available through Magazines Direct – where you can also find the latest deals .

YM is packed with information to help you get the most from your time on the water.

- Take your seamanship to the next level with tips, advice and skills from our experts

- Impartial in-depth reviews of the latest yachts and equipment

- Cruising guides to help you reach those dream destinations

Follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

Sailing the Antarctic Island of South Georgia

- By Thies Matzen

- Updated: November 15, 2018

The Antarctic island of South Georgia is the most nerve-racking place I know. Along its spectacular coast — nearly 10,000 feet high in places, where hurricane-force winds can replace a flat calm in seconds — simply being there requires tenacity. Sailing away from the island is a kind of game of chance. Whether attempting the 800-nautical-mile upwind passage to the Falkland Islands or the 3,000-nautical-mile downwind one to Cape Town, South Africa, an oceanic gantlet of icebergs, fog and gales is unavoidable.

And getting there? That is also far from child’s play. On our Wanderer III , a 30-foot wooden boat with sextant and compass but no radar, weather forecasts or communication other than VHF radio, it’s pure psychology. Each phase of a voyage to the most fantastic island of the world is more than demanding.

When I first conjured up South Georgia as an idea, Kicki and I were still sailing in the Pacific. Later, in Cape Town, in 1997, after 10 years of being underway, a mere Atlantic passage separated us from a return to Europe. But I couldn’t get South Georgia out of my mind. I knew: If not now, then never. Rules and fees increasingly restrict the movements of curious sailors and simple boats like Wanderer III . Exploration has been replaced by tourism and orderly experiences, even at the far reaches of the planet.

So we recast our thoughts and actions. We sailed 55 days, first to Montevideo, Uruguay, for the cakes at the Cafe Rheingold, then on to a face-lift for Wanderer in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and finally to the Falklands — this last step in borrowed foul-weather gear. With our necks and backs suddenly no longer wet, we were encouraged to aim for South Georgia, after the winter.