Marinatown Yacht Harbour

Play in the heart of downtown baltimore, marina info.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is a liveaboard marina with 135 deep water slips that offers annual, monthly and daily rates. The marina has 30, 50 and 100 amp power services along with water, phone and wireless internet hookups. The marina offers a pump-out service, laundry, large beautiful pool, and bathroom facilities. At this marina you will find a diversity of people from people who own corporations to people that have sailed around the world. We have families that have lived here over 30 years and raised their children. These people are good, honest and hardworking always helping their neighbor. You will not find a better marina neighborhood to dock at.The marina is located across the river from historic downtown Fort Myers. Where there are many restaurants and historical sites to visit. Many festivals and other activities are frequently held at Centennial Park which is at the base of the south side of the bridge. It is about a five to ten minute dinghy ride from the marina. The marina is about twenty minutes driving time away from Southwest Florida International Airport and 15 minutes to 30 minutes from Fort Myers Beach and Sanibel Island.

Location Info

- Mega Yacht Slips

Transient rate $1.50 per foot per day. Month to month $12. fooot. Annual rate $11. foot. Live aboard fee $40 month single, $75 per couple. No other charge except electric which is metered

This marina does not require a credit card to hold the slip or any type of deposit. As a courtesy please notify the marina if you need to cancel your reservation at least 24 hours in advance.

Fuel Prices

Payment types.

Max Length (ft):

Approach depth (ft): , dock depth (ft):.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour

- Total Slips: 135

- Max Length: 75'

- Approach Depth: 6'

- Dock Depth: 12'

The marina is located across the river from historic downtown Fort Myers. Where there are many restaurants and historical sites to visit. Many festivals and other activities are frequently held at Centennial Park which is at the base of the south side of the bridge. It is about a five to ten minute dinghy ride from the marina. The marina is about twenty minutes driving time away from Southwest Florida International Airport and 15 minutes to 30 minutes from Fort Myers Beach and Sanibel Island.

Cruising Club Discounts

- Bait & Tackle

- Golf Nearby

- Groceries Nearby

- Hotel/Lodging Nearby

- Laundry Facilities

- Medical Facilities Nearby

- Post Office Nearby

- Restaurant Nearby

- Service/Maintenance

- Swimming Pool

Rates / Policies

Rates Transient rate $1.50 per foot per day. Month to month $12. fooot. Annual rate $11. foot. Live aboard fee $40 month single, $75 per couple. No other charge except electric which is metered

Policies This marina does not require a credit card to hold the slip or any type of deposit. As a courtesy please notify the marina if you need to cancel your reservation at least 24 hours in advance.

Additional Information

- Fax: 239-997-6407

- Latitude: 26.66043

- Longitude: -81.89038

Find a Marina

Fuel search, search for discounts, search marinas to make a reservation, find an article, you must be logged in to make a reservation.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Not a Marinalife Member? Sign-up for our Digital Subscriber membership today to reserve with this marina online!

Marinatown a delightful village for music, dining, shopping

As the happy hour singer finishes a tune on the small stage in T.P. Hoolihan’s Irish Pub, the crowd applauds raucously, and someone requests a favorite song. Step outside and the party next door at the Nauti Parrot Tiki Hut is so “nauti” that it has spilled out of the giant chickee hut, with people playing corn hole by the canal while a musician sings and strums a guitar inside. A few more steps down the canal walk, at Cactus Jack Southwest Bar & Grill, a trio belts out Motown as some diners watch from under the thatched roof.

A tree-filled patio between Cactus Jack and the First Mate & Bait Rentals and Boutique provides an inviting place to plop into one of the chairs, especially if the First Mate’s owner has fired up her outdoor fireplace. A stairwell leads to the second floor over the store, which houses the Fitness & Yoga at Marinatown studio. Take a few steps more, alongside people walking their dogs, to arrive at the newly opened Cantina Sol, which has a row of individually canopied glider booths overlooking the boats and the water. This enchanted place along the canal is Marinatown in North Fort Myers.

“I just think it’s a hidden little spot up there,” said Scotty Bryan, the Friday happy hour singer at T.P. Hoolihan’s. “You’d be amazed the number of times I’ve said, ‘I’m playing up in Marinatown,’ and they say, ‘Now, where’s that at?’ It’s right on the water, and you got four cool bars out there. They got all kinds of things going on, like kayak rentals and stores.”

Marinatown has the vibe you expect to find when you come to Florida — a laid-back, friendly atmosphere with a relaxed pace. Colorful characters who seem straight from Jimmy Buffett songs will strike up conversations with you at the bars, and many of them live the simple life aboard the boats docked at the marina. This lifestyle still exists in Florida, but increasingly in small enclaves hemmed in by private, gated developments and rushing, six-lane roads. However, Marinatown is one place where the laid-back life is accessible for the public to visit. It’s a self-contained pub crawl in one complex with different flavors of music, food and libations to sample in a single evening.

“It’s just a really cool feel when you have all of the places going with music that you can pick from, and you can walk back and forth,” Bryan said. “It’s like a little boardwalk full of entertainment. You get full bands, single acts, duos and you might get a guy on the piano. You can pop into a place, get a beer and take off, and stop at the next place to see whose playing.”

Bryan plays James Taylor, Jimmy Buffett, trop-rock songs and other music ranging from the 70s to the 90s. Sometimes it takes a minute to identify the songs because, with his dedication to interpretive performance, Bryan makes the songs his own. He isn’t just another three-chord guitar strummer.

While Bryan plays beach-style music, T.P. Hoolihan’s itself has been so painstakingly created that it seems as if the pub has been teleported from Ireland and plopped down on this canal in Southwest Florida. Likewise, much of the menu is transported from Ireland as well, featuring classics such as bangers and mash as well as fish and chips. Bryan said his favorite Hoolihan’s entre is the shepherd’s pie.

The Nauti Parrot really does have a blue-and-gold macaw named Nauti who hangs out on a jungle gym by the entry from the canal walk. While he doesn’t seem to talk, he has picked up a sound effect — he barks. Specifically, he makes the “ruff, ruff” sound that humans make when they imitate dogs, so he is a parrot who imitates humans imitating dogs. The place offers music seven days a week – and sometimes twice a day – in its chickee hut. The atmosphere is that of a Florida dive bar but in the most affectionate sense of the word.

“That place is usually pretty crowded,” Bryan said. “It’s an outside thing right on the water, and they’ve got the music out there, so it stays pretty crowded from what I’ve seen.”

New owners purchased Cactus Jack a little over a year ago. They kept the best items from the Tex-Mex menu while adding a few favorites from their native Britain. The restaurant is the only one of the four that serves breakfast — the traditional full British breakfast — although it is limited to Saturday mornings at this time.

Cantina Sol, the newest edition to the Marinatown restaurant row, opened Dec. 1. The menu offers Mexican-inspired fare as well as seafood and raw bar dishes, all served with a fine-dining-chef’s flair but at reasonable prices. Half of the current menu features appetizers and small-plate items, and gluten-free dishes are marked.

Co-owner Ron Ruzgis said the current menu reflects the restaurant’s soft opening, with more entrees to be added in the next couple of months as his team puts the finishing touches on the place. The restaurant leans toward sports with 18 televisions, specials on 100-ounce towers of beer and a subscription to the NFL Sunday Ticket.

The chicken mole verde tacos from the small-plate section of the menu come two on a slate platter with a side of roasted red pepper rice for $5.95. The shredded chicken is moist and flavorful but not overly hot with a tasty spicing, and the kitchen serves up a generous portion of meat in the soft corn tortillas. The cabbage slaw topping stands up with a superior crunch than lettuce would offer, adding texture to the tacos that also feature chicuacua cheese and pico de gallo. Although the bartender offers sour cream, ask for a wedge of lime instead as the perfect condiment to squeeze over these tacos.

Even Marinatown’s yoga studio gets into happy hour with a once-a-month “wine-down” Friday evening yoga class followed by a social hour with hors d’oevurs, wine and a guest speaker. The next one takes place this Friday at 5:30 p.m. The studio is also offering a charity event at 9:30 a.m. on Sunday. “Nama-Stray” will be a yoga class offered in exchange for a donation to Cape Coral’s PB&J Animal Rescue and will include a meet-and-greet with adoptable pets.

First Mate & Bait Rentals and Boutique has proven to be an experiment in progress for owner Danielle Tabone. She opened the place about 18 months ago as a paddle-craft rental and convenience store. The coffee area in the store simply resulted in her trying to give away free coffee. While coffee and snacks didn’t go over so well, the coolers of cold refreshments have taken off — particularly the beer and wine — so she is expanding her inventory selection of those items. Her biggest business surprise, however, was the transformation of her store into a resort-clothing boutique.

“I opened the doors and threw a couple of dresses and a purse out, figuring I’d only sell a couple, but I sell dresses all day long,” Tabone said. “They took off. They’re unique and Floridian. I own one of everything (the clothing) that I sell.”

Most of the clothing she carries is American made, and she sells resort-style clothing in sizes up to 3X on some items. For being boutique quality, the prices are quite reasonable. The clothing has proven so popular that it has taken over half of the store.

Tabone installed a fitting room in the corner of the coffee area to accommodate her burgeoning boutique business, and she now is in the midst of converting the rest of the coffee space into a retail sales area for quality paddleboards, kayaks and paddling accessories to complement her paddle sport rental business.

She keeps the store open until at least 8 p.m. and sometimes as late as 10 p.m. on the weekends when Marinatown really gets hopping.

“You can’t get much better than Marinatown,” she said. “This is heaven.”

Connect with this writer: @LauraTichySmith (Twitter)

Marinatown Yacht Harbor

Where: 3446 Marinatown Lane, North Fort Myers

Features: Cactus Jack Southwest Bar & Grill; Cantina Sol; First Mate & Bait Rentals and Boutique; Fitness & Yoga at Marinatown; Nauti Parrot Tiki Hut; T.P. Hoolihan’s Irish Pub

Info: marinatown.net (links to all businesses’ websites except firstmateandbait.net and facebook.com/cactusjackwaterfrontgrill)

By land: Marinatown is located on the south side of Hancock Bridge Parkway about 2/10 of a mile west of U.S. 41.

By sea: Marinatown is on a canal just off of Hancock Creek on the north shore of the Caloosahatchee River at ICW marker 52. The channel can run as shallow as five feet at low tide, so check Marinatown’s website under the location tab for current navigational information.

Special event: Marinatown offers a farm market on Fridays from 9 a.m.-1 p.m.

Marinatown Yacht Harbor

No reviews submitted yet.

Reserve a Boat Slip

Distinctly fort myers.

Welcome to Sunset Harbor Village, a vibrant marina community with boat slips, office space and restaurants nestled in the heart of North Fort Myers, Florida, where the waters glisten, and the possibilities are endless.

Boaters and Offices enjoy full access to marina amenities and a unique waterfront living experience including casual waterfront dining, and exciting activities to create the perfect balance between work and play.

The Marina at Sunset Harbor Village

Sunset Harbor Village is the perfect destination for boating year-round. With its close proximity to the Gulf of Mexico and the Intracoastal Waterway, Sunset Harbor offers countless opportunities for exploration and adventure on the water.

Livaboard your boat at Sunset Harbor Village and gain access to all the marina amenities .

BOAT SLIPS 135

Sunset harbor village marina amenities.

- 135 Waterslips, 25′ – 75′

- 30/50 amp Power

- Pump Out Service

- Newly Renovated Swimming Pool

- Laundry Machines

- New Restroom & Showers

- Season, Annual dockage

- Liveaboards

OFFICE SUITES 41

Sunset harbor village office suites.

- Starting at $750/month

- Includes Utilities & Amenities

- Individually controlled HVAC

- Windowed Offices

- Conference Rooms

- Coffee & Tea

- Kitchenette/Lounge

- Gym (Coming Soon)

- Business Center

It's Time to Play!

Sunset Harbor Village is all about FUN! Living aboard your boat at Sunset Harbor Village marina means endless opportunities for water-based activities right at your doorstep. Whether you enjoy fishing, kayaking, paddleboarding , or simply cruising the open waters, you’ll have it all within easy reach.

Enjoy our newly remodeled swimming pool and outdoor lifestyle with kayak, boat, and bicycle rentals, and sand volleyball court. Sunset Harbor Marina members enjoy full access to all amenities.

Sunset Harbor Village Amenities

- Gym (Coming Soon)

- Mail Service

- Kayak, Boat & Bike Rentals

- Volleyball Court

Happy Hour on the Water

Whether you’ve spent a day on the water or a busy day at the office in the Sunset Harbor Village suites, unwind and join us at our Margaritaville-style restaurants for delicious food, refreshing drinks, and weekly entertainment – just as you are.

RESTAURANTS

Sunset harbor village restaurants: two tiki's are better than one.

Enjoy Sunset Harbor Village’s On-Site Restaurants and One-of-A-Kind Largest Tiki Hut in Lee County.

Sea-Craft Waterfront Tiki Blackbeards Tavern Nauti Parrot Tiki Hut Cheeks

MARINA HOURS

[email protected] Office: 239-997-7711

Sunset Harbor Village 3444 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, Florida 33903

Thank You for Contacting Sunset Harbor Village

Marinatown Yacht Harbour

Address: 3444 Marinatown Lane, # C Fort Myers, FL 33903

Phone: (239) 997-7711

About Marinatown Yacht Harbour

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is located at 3444 Marinatown Lane, # C Fort Myers, FL 33903. They can be contacted via phone at (239) 997-7711 for pricing, directions, reservations and more.

QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

What is the phone number for marinatown yacht harbour.

The phone number for Marinatown Yacht Harbour is (239) 997-7711.

Where is Marinatown Yacht Harbour located?

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is located at 3444 Marinatown Lane # C, Fort Myers, FL 33903

What is the internet address for Marinatown Yacht Harbour?

The website (URL) for Marinatown Yacht Harbour is

What is the latitude and longitude of Marinatown Yacht Harbour?

You can use Latitude: 26.66052060 Longitude: -81.89129100 coordinates in your GPS.

Is there a key contact at Marinatown Yacht Harbour?

You can contact Marinatown Yacht Harbour at (239) 997-7711.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour Reviews

Nearby marinas.

Mulberry Point Yacht Harbor

0.00 Mile (s)

Best Western Fort Myers Waterfront

0.77 Mile (s)

Prosperity Pointe Marina

1.49 Mile (s)

Legacy Harbour Marina

2.66 Mile (s)

Marina Reviews

- Claim Marina

Cloud Cover:

Rain Chance:

Visibility:

H: o F L: o F

- Things to Do

- Travel & Explore

- Investigations

- Marketplace

- Advertise with Us

Video of the Day

Marinas That Allow Live-Aboards in Florida

If you’re looking to fulfill your dream of a simpler life, living aboard your boat on the water, you’ll find a handful of marinas in Florida that will help you make this dream come true. Despite this state's extensive coastline with thousands of marinas, only a small percentage of these welcome live-aboards. Most marinas require standard liability and a security deposit for all long term live-aboards.

Seafarers Marina

Approximately five miles from downtown Jacksonville, you’ll find Seafarers Marina on the Trout River. This marina offers 75 slips, with finger docks, electricity and water available for rent on a live-aboard, overnight, weekly and monthly basis. Amenities include grill area, laundry, shower facilities and internet access in the office during business hours.

Seafarers Marina 455 Trout River Dr. Jacksonville, FL 32208 904-765-8152 seafarersmarina.com

Lighthouse Point Marina

Lighthouse Point Marina is located in the small southern Florida town of Lighthouse Point, minutes from Hillsboro Inlet. The marina has more than 100 slips, able to accommodate vessels up to 80 feet in length. Amenities include laundry facilities, mail room, heated swimming pool, tennis court and ship store. Live-aboards are welcome and dockage is available for rent on an annual or transient basis.

Lighthouse Point Marina 2831 Marina Circle Lighthouse Point, FL 33064 954-941-0227 lhpmarina.com

- Royale Palm Yacht Basin

Located in Dania, in south Florida, the Royale Palm Yacht Basin welcomes live- aboarders with slips that can accommodate vessels up to 80 feet in length. Amenities include 30- and 50-amp service, cable TV, laundry facilities, restrooms and showers.

Royale Palm Yacht Basin 629 NE 3rd Street, Dania, FL 33004 954-923-5900 royalepalm.com

- Sombrero Marina

You can dock your boat and live aboard at Sombrero Marina in Marathon on Boot Key Harbor, one of the best protected harbours of the Florida Keys. The marina’s slips can accommodate boats up to 85 feet in length and the marina offers amenities, including Wi-Fi, laundry facilities and showers.

Sombrero Marina 35 Sombrero Blvd Marathon, FL 33050 305-743-0000 sombreromarina.com

- Marinatown Yacht Harbor

Marinatown Yacht Harbor in Fort Meyers is a live-aboard marina with 135 slips available for rent on an annual, monthly or daily basis. Amenities include 30- to 100-amp electrical connections, swimming pool, bathrooms and laundry facilities.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour 3446 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, FL 3390 239-997-2767 marinatown.net

About the Author

A resident of Toronto, Joy Kimber has been writing online since 2009. She provides travel-related content for LIVESTRONG Lifestyle and enjoys writing articles that focus on business, career, and psychology for eHow. She holds a Bachelor of Commerce and Administration from Bishop's University.

DoubleTree by Hilton Moscow - Marina

Arrival Time

Enjoy a luxury stay by the Royal Yacht Club

Enjoy a chic stay at our hotel, adjacent to the Royal Yacht Club. We're one kilometer from Vodny metro station, which gets you into Moscow in 27 minutes. Otkritie Arena and Sheremetyevo - A.S. Pushkin International Airport can be reached in 20 minutes. We have a Balinese-inspired spa and a pool with private pods to relax in.

Our amenities

Non-smoking rooms

On-site restaurant

Indoor pool

Fitness center

Room service

Business center

Meeting rooms

Pets not allowed

Rooms and suites

Hilton Honors member benefits

Hilton Honors Discount rate

Points toward free nights and more

Choose Your Room

Digital Check-In

Hilton Honors Experiences

Digital Key

Group travel and events

Location and transportation.

Airport shuttle

Not available

Marinatown Yacht Harbour

North Fort Myers, FL | N 26° 39.600' / W 081° 53.480'

3446 Marinatown Lane

North Fort Myers, FL 33903

Mile Marker

Location Reference Point

Suggest Edits

Marina Login

/-81.8913333333,26.66,12/800x450?access_token=pk.eyJ1Ijoid2F0ZXJ3YXlndWlkZSIsImEiOiJGRmM1RDdzIn0.Wya5yV5QEqbz0-fct8zyIA)

Contact Request

Your request has been sent to the dockmaster at Marinatown Yacht Harbour

Repair Capabilities

Engine (Inboard)

Engine (Outboard)

Electrical (AC)

Electrical (DC)

Solar/Wind Power System

Navigation System

AV Entertainment

Climate Control

Refrigeration

Plumbing Sanitation

Carpentry Woodworking

Paint Varnish

Sail System

Canvas Upholstery

- Download The App

- Destinations

- Knowledge Center

Apple Sign-In

Sign up to get Navigation Alerts and News delivered to your inbox!

Invalid Email

Invalid Captcha

Check out our latest newsletter

Newsletter Sign-Up

The "kitchen" on a cruising boat is referred to as the .

The captcha question was answered incorrectly.

The email is invalid. Please close the modal window and try again.

Signing-up...

International Perspectives on Suburbanization pp 177–191 Cite as

Khimki in Moscow City-region: From ‘Closed City’ to ‘Edge City’?

- Oleg Golubchikov ,

- Nicholas A. Phelps &

- Alla Makhrova

577 Accesses

3 Citations

Many concepts in social sciences sooner or later face ‘trial by geography’ — a consideration of their applicability beyond specific places and contexts, thus allowing these concepts to be either adjusted or rethought. The interest of this chapter is, then, to bring the analysis of post-suburbia from the Western economies into the former ‘Second World’ and to consider to what extent the ideas of ‘edge city’ (Garreau, 1991), ‘post-suburbia’ (Kling et al, 1995) and associated models of urban growth may apply for the latter. To this end we consider urban development and place-making on the periphery of Moscow. The analysis here is particularly based on the case of Khimki — a former Soviet off-limits ‘satellite city’ of Moscow and more recently a fast-growing area featuring many new retail, office and housing development projects right at Moscow’s edge.

- Urban Development

- Urban Planning

- Moscow Oblast

- Civic Group

- Chief Architect

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University College London, UK

Nicholas A. Phelps

Cardiff University, UK

Copyright information

© 2011 Oleg Golubchikov, Nicholas A. Phelps and Alla Makhrova

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Golubchikov, O., Phelps, N.A., Makhrova, A. (2011). Khimki in Moscow City-region: From ‘Closed City’ to ‘Edge City’?. In: Phelps, N.A., Wu, F. (eds) International Perspectives on Suburbanization. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308626_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230308626_10

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-32513-9

Online ISBN : 978-0-230-30862-6

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social Sciences Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- About Washington Rowing

- University of Washington

- Conibear Shellhouse

- Montlake Cut

- Washington Rowing Stewards

- Emergency Action Plan/W.E.T. Plan

- Featured Stories/Press Releases

- Live Stream

- SWEEP Magazine

- Women’s Crew Overview

- Women’s Roster

- Women’s Coaches

- Men’s Crew Overview

- Men’s Roster

- Men’s Coaches

- History Overview

- Women’s History

- The Boys in the Boat

- UW/Cal Dual

- Conny and the Husky II Restoration

- The History of the Varsity Boat Club

- Pac-12 Champions

- National Champions

- Donate to Washington Rowing

- Alumni Connections

- Alumni Tailgate

- Class Day Cruise & Barbecue

- Turkey Trot

- Windermere Cup Stewards’ Enclosure

- Women’s Team Brunch

- Booster Do’s and Don’ts

- Board of Rowing Stewards

- Recruiting Info

- Financial Aid Services

- NIL Information

- UW Women’s Rowing Virtual Tour

- Women of Washington Rowing Camps

- Contact Washington Rowing

- BITB ’36 Tour

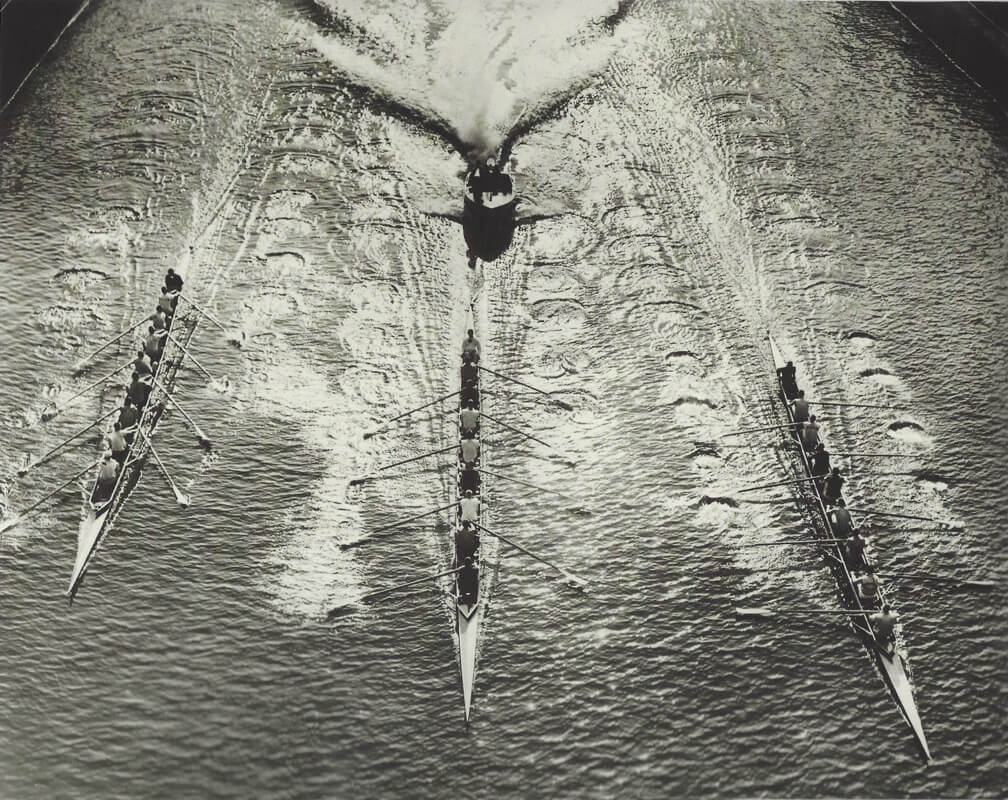

Men's Crew:

World War II brought global changes, collegiate athletics included. Training techniques were changing. Equipment was changing. So too were the students entering the University.

By 1950 the crew team was enjoying the first full year in a new, state of the art building – Conibear Shellhouse. George Pocock, now in his fifth decade with the team, had his own shop on site, and Al Ulbrickson had an office with a view. Hiram Conibear would have been speechless (momentarily).

But even though the complexion of rowing was rapidly changing, the fifties would be traditional in one sense: the events and results would be unpredictable. In fact, the decade served up one of the most improbable of victories, and would end with the retirement of two of the greatest legends in the sport. These events alone would thrust the program in a new direction, and would lay the groundwork for the modern age of Washington rowing.

With the equipment moved in the summer of ’49, and crew members reporting to the new shellhouse in droves during the fall, there was only one problem: there weren’t any docks. Even by the winter, with George Pocock now ensconced in his new shop (the northernmost boat bay of the shellhouse), the docks were not installed. Probably all the better for him, as he became comfortable in his new, modern surroundings, and produced two new shells, the Tyee and the Totem.

The men, however, would have to wait. The winter of 1949-50 is still the coldest on record in Seattle, and the blizzard of January 1950 is considered one of the major weather events of the 20th century in Washington State (see Washington State Top Ten 20th Century Weather Events.) The crewhouse opening iced over and stayed that way. A desperate Stan Pocock, in his first year as freshmen coach (Gus Eriksen had left for the head coaching job at Syracuse), had the freshmen lay a path with scrap lumber across the frozen marsh out to the lake so they could get on the water.

By mid-winter the docks were in and the varsity was out on the lake as well. To make up for lost time, Ulbrickson lengthened workouts and powered through spring break with two-a-days. A dual race with Wisconsin on Lake Washington in April was an opportunity for both schools to hone their racing skills; unfortunately, true to form, the weather was so miserable on the Seward Park course that Wisconsin’s varsity almost sunk – forcing the officials to stop the race, with Washington leading midway through. It was not raced over.

But the Dual on the Estuary, later in the year, featured the highest level of collegiate boat racing with both California and Washington boating exceptional, experienced crews. In the freshmen race, Washington prevailed by open water, but the JV’s could not overcome the traditionally quick starting Bears, losing by open water to a strong crew. The varsity also fell victim to Cal’s start, but slowly inched their way back. By two miles, the crews were even, and together sprinted to the finish with Washington winning by about a half length. It was one of those rare three mile races where the crews were never separated by more than a few seats, Washington prevailing against a deep Cal crew on the strength of Ulbrickson’s unrelenting spring conditioning campaign.

The IRA’s were moved to the Ohio River at Marietta, Ohio in 1950 to alleviate the concerns as discussed in 1949. There were more places to stay for the number of competitors (albeit veteran’s housing with outdoor plumbing), and the river current could be controlled on race day using upriver dams. Well, most of the time that is. But not on June 17th, 1950. Due to torrential rain storms, the Muskingum River (which entered the Ohio at the one mile mark of the course) flooded. As it entered the course, it carried with it anything that could float (use your imagination). All the events would now have to be shortened.

Over a course of about one and a half miles (a little longer), the freshmen began the day with a two length win, never seriously challenged and completing an undefeated season. The JV’s followed with a surprise win in their shortened two mile event. The abbreviated (two mile) varsity race went bad at the start – Wisconsin, California, and Stanford pulling out to an open water lead. With less distance in the race, this could have been devastating for Washington, but the Huskies settled and maintained their position, watching as Navy hit a marker buoy and dropped out. The last half mile was all Washington, as Ulbrickson’s men just powered through the competition to win by three lengths going away. As an indication of the continued dominance of western rowing, Cal, Wisconsin, and Stanford finished second through fourth in that order.

The men of 1950 completed the fourth sweep of the national championships in the history of the program. The conditioning of all three crews was exceptional, but it was the experience in the varsity and JV boats that made these teams so unique. In fact, due to their 1947 post-season race as an (almost) all freshmen varsity, Norm Buvick, Rod Johnson, Bob Young, and Al Morgan – all members of the 1950 national champion varsity eight – received their fourth varsity letter. They, along with JV oar and 1948 gold medalist Warren Westlund, joined Hal Waller (1915) and Bart Lovejoy (1909) as the only men in the first fifty years to do so.

With the resurgence of the Stanford program in 1950 and a fourth place finish at the IRA, the team came north with California to race on the Seward Park course in the spring of ’51. Not since 1916 had the three schools lined up together for the traditional “triangular” regatta on Lake Washington.

The start was about as close as Stanford would come to the competition, but as a burgeoning club crew it was that much better that they were back. In both the freshmen and JV races, California stormed out in front, with Washington pulling back through the Bears to win by open water. In the varsity event, the Huskies were ahead by open water with less than a mile gone, and cruised home in 15:39. But the JV’s time of 15:29 – ten seconds faster than the varsity – indicated the challenge of their race and the depth of Ulbrickson’s squad.

Marietta was once again home for the IRA’s, and this time the Ohio River itself was utterly out of control. Upstate rains led to a thirty foot rise in the river in twenty-four hours. The stake boats in the current were useless – made more so when they washed away by the evening. Debris was everywhere. After the Navy Plebes crossed in front of a navigation buoy when lining up for the freshmen race, their boat was sunk in the collision. Rusty Callow – in his first year as the head coach at Navy (after two decades at Penn) – was at the wrong end of a trifecta of sorts: all of his crews either hit buoys or otherwise wrecked before even racing.

The races were again shortened to two miles, but with the course going downstream the “real” distance – i.e. the number of strokes required to get from the start to the finish – was significantly shorter. Overnight the race had become a sprint. With the freshmen race now postponed, the JV race started in near chaos, with California winning over a re-vamped Husky crew (two alternates were switched in two days before the race) in second. Navy sank after sheering off the rudder of the Princeton boat, the Princeton coxswain attempting to steer his crew down the swollen river with his hands.

The varsity race was even more bizarre. The stakeboats were rocking wildly in the current. As the starter screamed the commands, the boats were off, with Wisconsin moving to a length lead in the first twenty strokes ((1) – see photo below)). Washington put in a gallant effort, but could not make up for the lost time. The Badgers, coached by former Husky Norm Sonju (see 1925-1927) who had recently moved from an assistant under Stork Sanford at Cornell, finished the race in 7:50 – about half the time of a regular three miler.

The freshmen race was pulled off at dusk. The stake boats were somewhere near Cincinnati by then. At the floating start, Washington sunk their blades in to the water to meet not water, but the roof of a house. Thrashing wildly, they dislodged themselves, and in a race reflecting maturity beyond their years, coolly rowed back through every crew on the course, finally flying by MIT and Navy (Navy had borrowed another boat) to win in the last 200 meters.

Needless to say, that was it for Marietta. A town that had poured their heart and soul into putting on a national event just could not beat back the elements. Ironically, a year later while the crews waited out the delays on the windy shore of Lake Onandoga – the new site of the IRA’s – the Ohio River at Marietta sat blissfully at “pool stage”, lapping at the river bank like a pond.

Loyal Shoudy had died earlier in the year, and in his absence the banquet died too. But this would be the only year that would happen. The banquet was quickly revived in 1953, and would serve for another twenty years as a tribute to Loyal Shoudy, and as a tribute to each young man who represented Washington at the national championships.

Since the revival of the IRA’s after WWII in 1947, Washington was undefeated in the freshmen event. For six years running the Steward’s Cup was home at Washington. The varsity squad was dominated by veteran oarsmen and national champions heading into another Olympic year.

So it was with confidence that the crews made it to the Estuary in April. California, however, had other things in mind, training with a vengeance throughout the spring. The Husky freshmen, in their opener, were defeated by a quarter length – the first time the freshmen had lost to Cal since 1941. The JV’s were subsequently defeated, leaving it up to a shocked varsity to hold off the sweep. They could not; California, stroking smoothly down the course, won by over four lengths. This was the first sweep by California in the history of the Dual.

A stunned Washington crew boarded the trains for home. A team with such extraordinary potential had face-planted so abruptly that it would take nothing short of a miracle to fix the psychology at the boathouse. As the year progressed, Ulbrickson became visibly frustrated and uncharacteristically explosive. By the beginning of June he had dismissed half of the team.

Gus Eriksen had convinced the IRA Stewards to move the national championships to Lake Onondaga at Syracuse after the two-year debacle at Marietta. The men stayed at the fairgrounds, and temporary boathouses were erected at a nearby park on the lake. The lake was long and the community supportive. The only problems were wind, stifling heat, and a sickeningly polluted lake; although after Marietta, if you didn’t hit debris the size of a house, you were happy.

Ulbrickson took only his varsity and JV, the freshmen staying home due to their loss on the Estuary, and was forced to make last minute changes to these crews due to injury. Although the races were delayed due to the wind, the JV’s rallied in their three-miler to come up short only to Navy. The varsity, never able overcome the temperature and humidity, nor shed the baggage heaped on them at the Estuary, fell to an almost unbelievable seventh place.

Navy swept the events that year, and the 1952 victory would be one of 29 consecutive wins by this crew known as the “Great Eight”. Rusty Callow, taking the head coaching job at Navy in 1951, had focused on this group as freshmen; he took them straight over to Worcester following the 1952 IRA’s for the Olympic Trials and they mowed down everyone on the 2000 meter course. Washington made the finals, but finished open water behind Navy and Princeton. Click here for more on a recent reunion of Navy’s Great Eight – an exceptional group of men coached by an exceptional man.

Ulbrickson, after the IRA’s, dismantled his varsity crew, taking four of his elite upper class oarsmen – seniors Carl Lovsted, and Al Ulbrickson Jr. and juniors Dick Wahlstrom and Fil Leanderson, added JV cox Al Rossi, and entered them in the four trials. The eight became an all-sophomore varsity, who, although losing at the trials, gained some important racing experience that week.

The four faced off against tough competition, including five members of the 1948 squad (including Warren Westlund and Bob Will) returning to the trials as a Seattle Athletic Club entry. Through two preliminarily races the crews advanced, to ultimately meet in the final. Ulbrickson’s hand picked crew finally defeated their older brethren in the final, and were off to Helsinki as the third crew representing Washington at the Olympics.

In Helsinki, the four went on to win the the bronze medal in a close race, falling to Czechoslovakia and Switzerland in the final. The “Great Eight” won the gold, as did Charlie Logg Jr. in the pair, son of the former Washington captain (1921) and long time crew coach at Rutgers.

Determination mixed with trepidation is probably a good way to describe the mentality at Conibear in the fall of ’52. Even though Washington was represented at the Olympics, most all of the confidence this team had was doused on the Estuary in 1952. Ulbrickson was equally unimpressed; his back and other ailments were allegedly causing him a significant amount of discomfort at the time and that didn’t help either.

By the springtime, the men had moved surplus bunk beds into the lounge area of the shellhouse and many of the squad moved in for spring break. Although feeding the men was a problem (a former merchant marine took up the duties during the week), Carmelia MacNichols, a friend of an athlete’s mother, took on the challenge for the rest of the year. (1,3) Room and board was now available at the crewhouse for the first time since Conibear’s men moved into the old lighthouse on Lake Union in 1910 – and was an instant morale booster.

The crews met California on Lake Washington with revenge in their eyes. The freshmen and JV’s won soundly, and the varsity, likely being reminded on virtually every stroke of their stinging defeat on the Estuary a year earlier, punished the Bears by seven lengths.

By late May the third boat and the JV’s had improved enough to be matching the varsity’s speed. By the time they got to Syracuse, Ulbrickson felt compelled to race off his varsity and JV’s; he did so Thursday night before the races on Saturday. The three mile race ended in another “tie” since it was so dark and the boats were close. The varsity got the nod this time, but “that contest cooked the varsity’s goose” says Stan Pocock (2).

The varsity turned in a good race on June 20th, falling short to Navy’s “Great Eight” and an improving Cornell squad. But the strong and experienced JV’s dominated their race start to finish, and the freshmen returned the Steward’s Cup back to Washington with an open water victory over Cornell and Princeton. The combined finishes were enough for the men to bring home the Ten Eyck trophy – the award for overall highest placing team at the IRA.

The team had turned the corner over spring break and never looked back. Most impressive, and a hallmark of Ulbrickson, was the depth of this squad. He would take that depth – and that momentum – with him into the next year.

With a new (plastic) roof over the shellhouse porch and bunk beds lining the boat bays, Conibear Shellhouse became the official home to the crew team. It may not have been the warmest place to sleep, and loud snoring tended to echo across the concrete walls, but nothing could beat waking up to the smell of fresh cedar emanating from George Pocock’s shop.

The strong bonding of this team showed on the Estuary in May, when an underdog freshmen squad defeated Cal by two lengths, and the varsity stroked to a lop-sided win, winning by over six lengths. Cal avoided the sweep by defeating the JV’s.

The racing at Syracuse on June 19th was typically hot and humid. The freshmen turned in a fierce effort, falling only to Cornell, but the JV’s had to settle for fourth after a line-up change and an inability to manage the steamy conditions. The varsity fell for the third straight year to Navy, with Cornell beating them to the line for second by about a half length, although after the race Navy would be disqualified for having an ineligible coxswain.

It was a difficult way to end the season but the results underscored the resurgence of east coast rowing, as Stork Sanford’s Cornell crews won both the JV and freshmen events (and varsity, if you count the Navy disqualification). Even so, Washington was close on the heels of these crews in all but the JV race, maintaining their reputation of being in the hunt at the end.

Another huge turnout at Conibear in the fall of 1954 spoke to the continued popularity of the sport in the northwest. Over 200 freshmen aspirants showed up at the crewhouse in October to try their chances at the eight seats available in the first boat.

The theme for 1955 might as well have been “eight seats”, for throughout the racing season Washington crews consistently were finishing races with less than eight men operating at full capacity. It began against Cal at the Dual on Lake Washington May 14th. The Varsity and freshmen won in dominant fashion, by over six and nine lengths respectively. The JV’s raced their three miles neck and neck and came storming into the last 300 meters even, when the Washington bow man crabbed and was ejected. A quick thinking Ivar Birkland, the Washington lightweight coach following the race in a launch, dove in to keep the exhausted young man afloat – while watching California row on by for the win.

The Western Sprints were inaugurated in 1955, the purpose to provide a larger schedule of races for the western crews and to promote the growth of the sport at other schools. (1) The shortened sprint distance of 2000 meters was chosen in an effort to level the field for those programs without miles and miles of practice water. Ulbrickson raced off his varsity and JV teams, with the JV squad winning the 2000 meter challenge and a trip to Los Angeles.

So just two weeks after the Cal Dual on a sweltering Newport Harbor, USC, UCLA, Washington, Cal, Oregon State, Stanford, UBC, and a specially invited Navy crew faced off for this varsity only event. Washington cruised through the prelims with the fastest time, but met their match that same day in the final against Navy, who won by about a length. The fading Huskies, punished by two races in the heat of the day, were even nipped at the finish by a resurgent Stanford squad.

On to Syracuse, where by now one would think the team would be prepared for the weather. But in the varsity event, this time the number two man fainted from heat exhaustion midway through the race, and the crew limped in for fourth place. The freshmen led their race handily from start to about 10 strokes from the finish, where Cornell, on the other side of the course, snuck by to win by feet. The JV’s, delayed an hour due to a lightning storm, could garner no better than fourth, also falling to Cornell, who swept the regatta.

Washington’s results at Syracuse were beginning to fall into a consistent, frustrating pattern. Always competitive, often ahead into the final mile, only to drop back severely by the finish due to exhaustion. There were stories of men found stumbling through the woods foaming at the mouth after races, and every year there were at least one if not more debilitated so severely mid-race that it affected the efficiency of the team. And although the heat of Syracuse was similar to other previous IRA venues, it was the humidity that was crushing. Hydration, physical preparation, and pre-race strategy were to become high priorities, but unfortunately for these men, not high enough in 1955.

The year ended in bitter disappointment for the team. This was a strong, experienced, and deep squad that did not meet their fullest potential by the end of the season. The frustration at that was palpable at a moribund Loyal Shoudy banquet. No pep talks would change it – only the opportunity to get back on the water and prepare for another year.

Fil Leanderson, freshmen coach at MIT under Jim McMillin (1934 – 37) was hired by Ulbrickson to replace Stan Pocock as freshman coach at Washington in the summer of 1955. An ample group of young men waited for their opportunity in Old Nero to learn the ropes from this veteran oarsman turned coach.

By spring the freshmen had a consistently fast squad, as did Ulbrickson’s varsity. On May 12th the team met Stanford on Lake Washington for their first test of the year. All three Washington crews won in dominant fashion, the freshmen and JV’s by over twenty seconds. A week later the men traveled by rail to the Bay Area to meet California; this time the Washington crews won by over ten seconds in each race, although Al Ulbrickson called the windy, rough conditions on the Estuary the “worst water I’ve seen in twenty years.” (1)

On May 28th, the team returned to meet the University of British Columbia on the Montlake 2000 meter course. UBC had earlier won the Canadian National Games and finished runner-up to Canada’s 1956 Olympic entry over 2000 meters. Washington, training for the three mile distance since winter turnout began, was a decided underdog. UBC cruised to an early lead, but the Huskies held close enough that by the time the crews entered the Cut they were even; now in command, the varsity opened up their lead to win in 6:02.6, with UBC crossing the line at 6:07.8. It was the third open water victory in three weeks for the team.

Once at the IRA’s though, Ulbrickson said “We did O.K. on the west coast but I can see we’re in a different league now.” (2) They were. On June 16th, in a biting headwind (but cooler conditions – in the seventies) Cornell’s varsity cruised to a third straight victory in the Challenge Cup, winning by lengths of open water over the closest runner-up Navy, with Wisconsin battling Washington to the line for third. The freshmen finished third behind Vic Michaelson’s (1938-40) Syracuse yearlings and second place Navy.

The JV’s were the story of the day for Washington. The crew fought hard against the headwind for a grueling three miles and drove home past Cornell to win the Kennedy Cup, completing an undefeated season.

Ulbrickson stayed with his varsity crews for the Olympic trials scheduled for June 28 -3oth on Lake Onondaga. At the trials, the varsity set a course record in their repechage of 6:19.9 over the 2000 meter course to advance to the finals, but were defeated by Yale, Cornell, and Navy (the Great Eight back to defend their title) in a wind blown final. Favored Cornell, as legend has it, raised their riggers an inch just before the final in an effort to avoid the heavy chop, but then were losing water over the blades on the drive. Yale, soundly defeated by Cornell at the Eastern Sprints only weeks earlier, won the trials and ultimately won the gold over Canada by a half length at the Olympics in Melbourne, Australia nearly five months later (the games were in late November).

Ulbrickson also entered a four from the JV boat, and the crew advanced into the finals, but were defeated by a West Side Club crew and Princeton.

Notwithstanding the JV victory at Syracuse, western rowing was now consistently taking a backseat to the eastern schools. Ebright – the master of the sprint race – did not even enter the trials, Cal finishing a dismal tenth in the varsity final at Syracuse and sixth in the JV’s. Stanford was on their way up, but were still a club crew, unsponsored by the university. First Navy’s Great Eight, and now an exceptional run by Stork Sanford’s Cornell squad (the trials loss would be their only loss in four consecutive years) and the Yale Olympic crew put eastern universities firmly on top of collegiate rowing since Washington’s sweep at Marietta in 1950. Something needed to give for the Washington program – and it would come via the most unlikely of events.

Athletics at the University of Washington took a decided turn on August 20, 1956. An announcement out of Denver, Colorado from the NCAA Council stated that due to football recruiting violations, “the University of Washington shall not be eligible to enter athletes or teams in National Collegiate Championship competition and the invitational and like events which cooperate with the NCAA…”. The ban would last two years.

It was not unforeseen. Twenty-five football players at Washington were implicated in a pay for play scheme in the mid-50’s that touched off similar findings at USC, UCLA and other schools. It was one of the most widespread scandals in college football history, and led to the final report in August of ’56 by the NCAA. However, the Pacific Coast Conference (the precursor to the Pac-10) and administers of the punishment, distinctly kept rowing out of the ban due to the uniquely amateur status of the sport, the fact it was not NCAA governed, and because the IRA was the one opportunity for west to meet east in rowing. So with that exemption, the crew prepared for the coming season with the same resolve and dedication that had produced champion crews of the past.

By February, with the team now in full workouts, news began to leak that the IRA was preparing to ban Washington from the regatta. The news was stunning; neither the NCAA nor the IRA had ever communicated that they would not accept the Pacific Conference ruling. On February 16th the IRA made it official: they would not invite Washington for the 1957 or 1958 regattas.

Seattle newspapers erupted at the story. The legislature in Olympia drafted a resolution calling for the ban to be overturned. Three separate appeals failed. The NCAA and IRA, in attempting to explain their actions, ended in the now infamous quote from the president of the NCAA – “The innocent have to suffer with the guilty.” To that, the Seattle Times responded that the NCAA “and a faint-hearted response by the stewards of the race are the sleazy combination which, to put it bluntly, gave the Huskies the works.” A seething Al Ulbrickson was direct: “It’s a lot of double talk. That’s it. We’ve had it.” (1)

It was a bitter pill to swallow. The timing was bad, the justifications weak, and the verbal attempts to explain it worse. The team sat there in the spring of 1957 dumbfounded at the fact that most of their junior and senior teammates would not row in the IRA’s again.

Ulbrickson had his work cut out for him, but the challenge and injustice seemed to re-ignite the fire inside this great competitor. His crews met California on Lake Washington in May and won by seven lengths in the varsity, seven and a half in the JV, and five in the freshmen races. One week later at the Redwood City Yacht Harbor, the crews mowed down Stanford by over five lengths in the varsity, seven in the JV, and seven in the freshmen races. It was an utterly dominant performance.

The crews stayed in training in hopes that their efforts would sway the decision makers at the IRA’s. It did not. After realizing their fate, the team cleaned out their lockers and left for summer jobs.

Stanford’s varsity, five lengths behind Washington a month earlier, would go on to place third at the IRA’s behind Cornell and Pennsylvania; there were no west coast entrants in the JV or freshmen events. Stork Sanford, Al Ulbrickson’s classmate and friend, then took his victorious Cornell varsity to Henley and won the Grand Challenge Cup later that summer.

That Cornell victory in England was a big story. Al Ulbrickson heard about it first hand, and went up to Orcas Island in the summer of ’57 to ponder his options for the coming year.

Al Ulbrickson had a whole summer on Orcas to study his options for 1958. It was clear that neither the NCAA nor the IRA had any intention of lifting the sanctions on Washington. He had felt since the 1956 JV victory that his crews were on the upswing, but the frustrations of that season paled in comparison to having a dominant squad in ’57 that was, in his mind, so unjustly punished. An alternative was not just required, but demanded.

It is unclear when the first whispers of a trip to Henley emerged, but by the winter the Stewards and Ulbrickson had agreed that if the varsity was worthy (i.e. undefeated), they should be sent to England. No Washington crew had ever raced at the Henley Regatta (the ’48 four won the Olympics at Henley but not as part of the Henley Regatta), and “On To Henley” became the rallying cry of the entire team.

In May the crew traveled south to meet the Bears on the Estuary for their first test. The freshmen and JV’s won handily, with the varsity cruising to an almost three length win to complete the third sweep in as many years. Stanford subsequently came north and, along with a visiting UBC squad, were defeated in record times (wind aided) by all three Washington crews over the Seward Park course. The varsity won in 14:07.1, and the JV’s in 14:15.5 in their respective three-mile races.

The final race of the year came on May 31, with Washington facing UBC at the 2000 meter sprint distance, along with OSU. Cruising down the Montlake Cut, Washington prevailed by a length over UBC, with OSU losing their stroke to a catapult-like crab in the final sprint. That win sealed the deal for the varsity: they would go to Henley.

The Stewards organized a classic “On To Henley” fund drive, similar to the first IRA drives set up by Hiram Conibear, and raised more than enough to send the varsity. The Seattle community, equally frustrated with the sanctions heaped on the team, were generous in their gifts and eager to see the team compete overseas. It was also about this time that it was becoming known that the Leningrad Trud Club – the Soviets – would be racing at Henley as well; in a behind the scenes negotiation, the U.S. State Department began working with State of Washington, University, and Soviet administrations to broker a post-Henley, “people to people” race in Moscow.

The deal done, the invitation to race in Moscow came after the crew was already at Henley. It was a good thing too, since morale was not high among the men. The weather was awful; it was constantly pouring, and the day before the draw the grounds men had pumped 10,000 gallons of water from the participant’s tents. It was cold and windy and wet, and some of the men had colds. Even so, Ulbrickson said “the crew is in good shape physically.” Coxswain John Bissett quipped “You can say we are ready.”

“Thunder and lightning signified the clash of the giants in the first round of the Grand” noted The London Times rowing reporter. (1) Maybe so, but this race was over in a hurry, with the strong Soviet crew blowing out of the gates to get a three-quarter length lead by the quarter mile, and lengthening to, in Henley terms, a virtually insurmountable one length lead by the half mile. The Russians then cruised down the thin course gradually drawing out to an open water win. “We’ve rowed in worse weather than this” said Ulbrickson. “We simply never got relaxed and swinging. The boys were too tense. They wanted it too much. They were trying too hard”. (2)

The Russians, never challenged in two subsequent races, went on to win the Grand by two and a half lengths. After digesting the loss, the men began to focus on the trip to Moscow, and after a few more days of training on the Thames, flew east. The Swiftsure, the team’s shell, was flown to Helsinki, then taken aboard a Soviet train to Moscow.

Once behind the Iron Curtain, the men were treated like VIP’s. They were escorted on sight-seeing trips and were the guests of honor at various receptions and events. Even so, the training on the open, choppy Khimki Reservoir was intense. Ulbrickson was also visibly upbeat, seemingly more relaxed. Maybe stroke John Sayre translated the thoughts of his coach when he said “We love that rough water – it felt just like Lake Washington.” (3)

On July 19th, the Huskies lined up against Leningrad Trud – their adversary from Henley – and five other top Russian crews for a 2000 meter race across a wind-blown and choppy Khimki Reservoir course. Into the quartering headwind, the crew got a much cleaner start than at Henley, with the Soviet Army crew and Leningrad only inching out into the lead. Stroking at a thirty-four, Sayre maintained a solid run and the crew began to move out to a lead. By midway, they were up by a half length over Leningrad with the rest falling back. In the final 1000 meters, the Huskies pulled away to win by open water. “The boat was really singing” said Bissett. “The boys rowed it perfect.”

The Soviet crowd cheered the Washington crew with a standing ovation. The team was showered with gifts at a post event function. The men had numerous pictures taken with their hosts. Ulbrickson called the anonymous donor of the Swiftsure to see if it was OK to leave the shell as a gesture of goodwill. It was. He did. It was a “people to people” event that rang true in both countries.

But though the political significance would be left to the politicians to debate, the athletic significance was clear. The victory was a stunning comeback for Washington in many ways: from the defeat at Henley to victory in Moscow; from the depths of a dubious probation to international acclaim. Years later Ulbrickson, explaining why he considered this season the highlight of his career, said “One item made the Moscow race a little more gratifying…we came back from a decisive defeat. No coach could have asked for more.” The athletes that rowed the Swiftsure that day carved their name into the Washington Hall of Fame; inducted in 1984, it was this crew that opened the doors of international competition to all future generations of Washington oarsmen.

A resurgent group of men met Ulbrickson at the crewhouse in the fall of 1958. The Seattle community had welcomed the 1958 crew back as heroes; there were award ceremonies and man of the year banquets and various events hailing the victory in Russia. Every politician worth their salt, at the height of the Cold War, wanted a photo op. The Washington crew team was very, very popular, and so was Al Ulbrickson.

The crew also knew that 1959 would be the first year to get back to Syracuse. Freshmen coach Fil Leanderson, and his assistant coaches John Bissett and Dick Erickson, had the men out of Old Nero early, with eleven shells of freshmen on the water within two weeks. Frosh turnouts then went to two afternoon sections, one group at 3:15, and the other at 4:35. Leanderson would take three shells, and Erickson and Bissett would take two boat’s worth in the barge, and the oarsmen would rotate from day to day.

In January came the announcement that Al Ulbrickson had decided to step down as head rowing coach at Washington. In his letter of resignation, Ulbrickson noted “After last summer’s campaign, I felt emotionally bankrupt and without the enthusiasm necessary to do the type of work I want to and to which the University and and the rowing squad are entitled.” He continued: “I am deeply appreciative of the confidence and the trust (the University) have place in me over the years. This goes double for the thousands of parents who have allowed, and encouraged, their sons to row, and to those same sons who made our rowing so successful. It is to justify this confidence, more than any single cause, that I have decided now is the time for change.” (1)

That just about said it all. Disbelief and shock among his current and former oarsmen was met with the understanding that after thirty-two years of coaching, Al needed a break – particularly given the spectrum of events of the last two years.

So it was that Fil Leanderson, the Olympic bronze medallist from the 1952 crew, former captain, former MIT freshmen coach, former lightweight and freshmen coach at Washington, ascended to become the sixth head coach to lead the program. Leanderson hired John Bissett, the 1958 varsity coxswain, as his assistant and freshman coach.

The team didn’t lose a beat. In their first race, they swept OSU at the sprint distance on Lake Washington (the varsity rowed the 2000 meters in 6:14, and in the JV event, as a testament to the depth on this squad, the third boat won the event). The team then swept the Beavers again on the Willamette a few weeks later. At the traditional three mile Dual with California, the team romped to open water wins in all events. On May 16th, the crew traveled to Redwood City to meet Stanford at three miles, winning by no less than seven lengths in each event.

The men left for Syracuse confident after such domination on the coast, but they wilted under the heat again. The varsity lost a member to exhaustion in the last mile after leading by open water through their race, limping home in fifth with seven men. The JV’s also faded badly, with California cruising by to win. The frosh lost to a good Cornell team, and rowed a strong race to finish second.

It was a tough way to end the year for Washington. The crews just could not shake the bugaboo that had chased them since the IRA’s moved to Syracuse in 1953. Even so, in his first year as head coach, Fil Leanderson still took home the Ten Eyck trophy for overall team performance, a deserved accolade for this deep and dedicated group of men.

For Ky Ebright, the master of the sprint race and thirty-five year coach at Cal, these would be his last races as head coach. Forced into retirement at age sixty-five, Ky stepped aside as Jim Lemmon, his assistant since 1947 and freshmen coach since 1954, became head coach at Cal.

Thus came the end of the Ulbrickson-Ebright era – a remarkable time in the history of collegiate rowing. These two men and their crews dominated the sport from the late twenties to the early fifties, combining for thirteen varsity national championships, six west coast sweeps at the IRA, and five separate Olympic gold medals and one bronze over five Olympics. Their competitive drive made each program work that much harder. Yet it is difficult to encapsulate the success these men had. Beyond the quantifiable came the thousands of young men, those that never sat in a varsity boat, leave the sport better men for the experience. Surely that is the legacy these coaches wanted, and that which truly defines them as great.

Sources for the 50’s: University of Washington, The Tyee, 1951 -1960; VBC Log Book, 1936-1955, MSCUA; VBC Log Book, 1954-1955, MSCUA; Henley Royal Regatta, A Celebration of 150 Years, Richard Burnell; The Log of Rowing at the University of California, 1870-1987, Jim Lemmon; Ready All! George Yeoman Pocock and Crew Racing, Gordon Newell; “Way Enough”, Recollections of a Life in Rowing; Stan Pocock; Masters Thesis: The History of Intercollegiate Rowing at the University of Washington through 1963, Al Ulbrickson Jr.; Sport Magazine, June 1958; The Seattle Post Intelligencer, various articles (specifics available on request); The Seattle Times, various articles (specifics available on request); A Short History of American Rowing, Thomas Mendenhall; Interviews with Stan Pocock, Irma Erickson, Art Griffin, and Carl Lovsted, 1/03.

Special thanks to Stan Pocock and Al Ulbrickson for providing the key sources of information for the 50’s, Guy Harper, Carl Lovsted, and to Andy Hovland for compiling the balance of information and pictures for the 1958 season.

COMMENTS

Marinatown Yacht Harbour. Is a liveaboard marina with 135 deep water slips that offers annual, monthly and daily rates. The marina has 30, 50 and 100 amp power services along with water, phone and wireless internet hookups. The marina offers a pump-out service, laundry, large beautiful pool, and bathroom facilities. At this marina you will find ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbour, North Fort Myers, FL, United States Marina. Find marina reviews, phone number, boat and yacht docks, slips, and moorings for rent at Marinatown Yacht Harbour. The 2023 Marinas.com Boaters' Choice Awards Recipients Are Here! See This Year's Marina Honorees ... Fort Myers Harbor:

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is a liveaboard marina with 135 deep water slips that offers annual, monthly and daily rates. The marina has 30, 50 and 100 amp power services along with water, phone and wireless internet hookups. The marina offers a pump-out service, laundry, large beautiful pool, and bathroom facilities. ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbour 3446 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, FL 33903 Phone: 239.997.7711 Fax: 239.997.6407 Email: ...

By land Marinatown Yacht Harbour is in North Fort Myers Florida. 400 yards west of US41 on the south side of Hancock Bridge Parkway. Look for the sign above for the entrance to the marina. The harbour master's address is 3444 Marinatown Ln. North Fort Myers Florida 33903 Marina Restaurants

Review for Marinatown Yacht Harbour. Reviewed by: L. Mark DeCicco on May 17, 2018 Vessel Type: Power LOA: 37' Draft: 4.0' Rating: 5. Nice safe marina for longer term stays, few overnight visits. Live a boards are OK, clean bathrooms, large unheated pool, four, yes 4 different restaurants with TIKI bars, bait store, Kayak rentals.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is a marina located in North Fort Myers, FL | N 26° 39.600', W 081° 53.480'

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is a liveaboard marina with 135 deep water slips that offers annual, monthly and daily rates. The marina has 30, 50 and 100 amp power services along with water, phone and wireless internet hookups. The marina offers a pump-out service, laundry, large beautiful pool, and bathroom facilities. ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbour. Marinas; If this is your business please contact us to be confirmed as an approved administrator. Business Contact Information. 3446 Marinatown La N. Fort Myers, 33903 . 239-997-2767. Visit Website. ... "Best Harbor" Contest "Women on the Water" ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbor. Where: 3446 Marinatown Lane, North Fort Myers. Features: Cactus Jack Southwest Bar & Grill; Cantina Sol; First Mate & Bait Rentals and Boutique; Fitness & Yoga at ...

Marinas, Boat Dealers, Fishing Charters, Waterfront Dining, Lodging, Diving, Attractions, Boat Repair, Snorkeling, Kayaking, Sailing, Watersports & More!

Sunset Harbor Village is a lively marina community in North Fort Myers, Florida with 135 Boat slips, over 40 office spaces, and 4 on-site restaurants. Boaters and professionals enjoy full access to marina amenities and casual waterfront dining. ... Sunset Harbor Village 3444 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, Florida 33903. Facebook Instagram ...

About Marinatown Yacht Harbour Marinatown Yacht Harbour is located at 3444 Marinatown Lane, # C Fort Myers, FL 33903. They can be contacted via phone at (239) 997-7711 for pricing, directions, reservations and more.

Marinatown Yacht Harbour 3446 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, FL 33903 Phone: 239.997.7711 Fax: 239.997.6407 Email: ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbor in Fort Meyers is a live-aboard marina with 135 slips available for rent on an annual, monthly or daily basis. Amenities include 30- to 100-amp electrical connections, swimming pool, bathrooms and laundry facilities. Marinatown Yacht Harbour 3446 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, FL 3390 239-997-2767.

Marinatown Yacht Harbor. 3446 Marinatown Ln North Fort Myers FL 33903. (239) 997-2767. Claim this business. (239) 997-2767. Website. More. Directions. Advertisement.

Enjoy a luxury stay by the Royal Yacht Club. Enjoy a chic stay at our hotel, adjacent to the Royal Yacht Club. We're one kilometer from Vodny metro station, which gets you into Moscow in 27 minutes. Otkritie Arena and Sheremetyevo - A.S. Pushkin International Airport can be reached in 20 minutes. We have a Balinese-inspired spa and a pool with ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbour Contacts You can call Vicki at 239-997- 7711 for information about the marina slips, office rentals and restaurant leasing or you can Email Vicki [email protected] : Marina Restaurants. Anchor In Bar and Grill. Cactus Jack 239-652-5787 . Catina Sol ...

Marinatown Yacht Harbour is a service facility located in North Fort Myers, FL | N 26° 39.600', W 081° 53.480'

To this end we consider urban development and place-making on the periphery of Moscow. The analysis here is particularly based on the case of Khimki — a former Soviet off-limits 'satellite city' of Moscow and more recently a fast-growing area featuring many new retail, office and housing development projects right at Moscow's edge.

Get directions to Rabochaya Street, 2А and view details like the building's postal code, description, photos, and reviews on each business in the building

Marinatown Yacht Harbour Video Tour Coming Soon Marina Restaurants . TP Hoolihan's Irish Pub. Cactus Jack 239-652-5787 . ... Nauti Parrot Tiki Hut . Marinatown Yacht Harbour 3446 Marinatown Lane North Fort Myers, FL 33903 Phone: 239.997.7711 Fax: ...

Men's Crew: 1950-1959 World War II brought global changes, collegiate athletics included. Training techniques were changing. Equipment was changing. So too were the students entering the University. By 1950 the crew team was enjoying the first full year in a new, state of the art building - Conibear Shellhouse. George Pocock, now in his fifth…