| With the Offshore Racing Council's formation of the IMS based ILC MAXI level rating class and the Transpac Yacht Club's announcement that it would use the ILC Maxi as the big boat limit for the 1995 Transpac Race, it was logical that California owner Larry Ellison and his representative David Thomson would commission the design for SAYONARA to sail in the Transpac Race, San Francisco Big Boat Series, and other ILC Maxi events. The requirements for Transpac, a reach and run type race, are quite different from typical round-the-buoys racing, and it was a real challenge to produce a single boat that could do well under both formats. To meet this challenge, SAYONARA has a hull design a little narrower than might be expected for round-the-buoys sailing and is long by ILC MAXI standards to suit the heavy air San Francisco conditions and the moderate air reaching and | Wind Whips Yacht Race Into a Struggle for LifeOne of the most massive sea rescue operations in Australian history continued today in the aftermath of an ocean yacht-racing disaster that officially claimed five lives and may take dozens more. Tales of trauma, terror and death reached the mainland in southeastern Australia as hundreds of bruised and battered survivors of a devastating South Pacific storm that started Sunday night came ashore. More than half of the 115 boats that began the 725-mile race from the mainland to southern Tasmania either were abandoned or forced to seek shelter. Race officials estimated that approximately 1,000 sailors began the race. “It doesn’t get much worse than this,” said Mike Howard of Los Angeles, reached by telephone just hours after arriving at the end of the 54-year-old Sydney-to-Hobart race. He was a crew member of the winning yacht Sayonara, a 79-foot maxi boat that had sufficient size to survive winds that reached 90 mph and swells as high as 35 feet. Howard underscored the danger of the situation when he said, “My philosophy is, if you fall off the boat, you die.” The owner of the San Francisco-based Sayonara, billionaire Larry Ellison, founder and CEO of computer giant Oracle, was shaken to tears. “It was just awful,” he told Associated Press. “I’ve never experienced anything remotely like this.” Asked if he’d come back again, Ellison said, “My first reaction is, not if I lived to a thousand years. But who knows?” Also aboard Sayonara was Lachlan Murdoch, son of Rupert Murdoch, media magnate and Los Angeles Dodger owner. Lachlan Murdoch is chief executive of News Limited Corp. Howard told The Times that casualty figures being unofficially disseminated among the arriving crews had eight dead and 16 more lost at sea. But Australian officials, reached later by The Times, strongly denied that the numbers were that high. “The absolute, as of this moment [midafternoon today in Australia] are five dead and one missing,” said David Gray, manager of public relations for the Australian Maritime Safety Authority, which had as many as 27 sea rescue vessels and 30 aircraft involved in the effort in the Bass Strait, one of the world’s most notoriously dangerous sailing stretches, about 250 miles south of Sydney. Because of the Bass Strait, this race is frequently referred to by veteran sailors as “Hell on Highwater.” At least 40 sailors were plucked from the water during Monday’s rescue. As of midday today, two of the dead sailors, on the 40-foot Australian boat Business Post Naiad, remained harnessed to the deck of their boat, adrift at sea but observed by rescue craft. One apparently died of a heart attack when the boat rolled over--a full 360 degrees--twice, while the other drowned during the rollovers when he was unable to release his safety harness. The other three official deaths were from the yacht Winston Churchill. Six members were rescued from life rafts, but three others were washed out to sea and presumed dead. The official death tally remained elusive. One report had a sixth death confirmed--British Olympic sailor Glyn Charles, who was washed off his boat Sunday night and presumed dead. He finished 11th in the Star Class at the Atlanta Olympics in 1996. Gray said the possibilities of more deaths could not be discounted. He said that about 40 boats sought shelter in the small port town of Eden, and that most arrived with broken masts and rigging. Upon arrival, many sailors were taken directly from boats by ambulance to hospitals, most suffering broken bones, dislocations and severe cuts. “There were just many, many injuries on those boats that were knocked down [blown flat on their side],” he said. “A lot of them rolled over, one twice. They really got pounded.” One report called the rescue area a “scene of orange life rafts heaved in roiling seas.” Another called it “towering seas that turned 40-foot yachts into tub toys, flipping them over, snapping their masts and swamping them with water.” Howard said the Sayonara, with its 23 crew members, had been fortunate to be so large and fast that it may have stayed in front of the worst parts of the storm. But that didn’t mean his trip was easy. “I was concerned for the boat, with the pounding we took for a good 48 hours of the race,” he said. “Sometimes, it was just survival conditions. Numerous times, you thought the boat was just going to split in two.” The worst disaster in yacht-racing history was the 1979 Fastnet race, where 15 sailors perished off the southwest coast of Ireland. In that race, 303 boats started, and only 85 finished, including the winning boat skippered by television magnate Ted Turner. Howard said that lessons learned from the Fastnet experience, and long discussed among sailors, still weren’t heeded in the Sydney-to-Hobart disaster--specifically, that it is safer to remain with the yacht than to abandon it for rubber rafts. “As soon as you inflate the raft, the wind is trying to blow it away from the boat,” he said. “You [need to] inflate it at the back of the boat, and it’s the last thing you get into.” More to Read 5 more rescued after tourist yacht sank in Egypt’s Red Sea Deep seas and tight spaces impede search for 6 missing after yacht sinks off Sicily A deadly crash on a Long Beach sunset cruise. Then, the fight to save survivorsSign up for Essential California The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning. You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times. More From the Los Angeles Times World & Nation Top-ranking NYPD officer abruptly resigns amid sexual misconduct allegations37 people die in a crash between a passenger bus and a truck in brazil, guatemala authorities raid ultra-orthodox jewish sect’s compound after abuse reports.  13 people, including children, die in stampedes at Nigerian Christmas charity eventsMost read in world & nation.  Democratic governors hammered Trump before election. Now they hope to work with him  Biden signs bill that averts government shutdown after days of upheaval Germans mourn after 5 killed and 200 injured in the suspected attack on a Christmas market Judge in Hunter Biden case sued over underage drinking party, alleged beating- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

- Ultimate Boating Giveaway

“I never ever mooned Larry Ellison”In his own words, Hasso Plattner recalls what happened at the 1996 Kenwood Cup, when his maxi Morning Glory lost its rig. As Larry Ellison has often told it, Plattner mooned his business and sporting rival as Ellison, on board his maxi Sayonara , was sailing by. Plattner has vehemently denied this. Here is his version of the events that day in Hawaii. “We had a business meeting and he told me he was building a maxi yacht, must be 1994 or ’95. My maxi, Morning Glory , came a year later, and from 1996 on we raced against each other. We were racing [at the Kenwood Cup in 1996] and we had a bad first race. Then we had a win in the second and we were about to win the next one and we would’ve been in the lead¿we were faster, we felt we were faster. I was sailing against [Chris] Dickson, but with Russell [Coutts]’s help. But I steered the whole time Dickson was steering Sayonara and our mast came down. It was the last tack before the windward mark, probably five boat lengths in front of the windward mark, and the whole s–t comes down. “ Sayonara was at that point probably 10 boat lengths behind us because we had a nice little America’s Cup start, we were both late. They had to jibe and nearly hit a spectator boat. We are the second to last boat over the line and they are the last boat over the line. But we were faster than all the other ones. Then it happened. That was probably the turning point. Until then, I tried to have a normal relationship with [Larry]. We had high waves in Hawaii, typical Kenwood Cup waves, our mast is broken at the second spreader. Somebody goes up in the mast, a French dentist, and cuts and cuts and cuts half of his thumb off. So he comes down, it’s bleeding, I still remember Matthew [Mason] saying, “Don’t look at it. Don’t look at it.” We had another dentist on board and within less than a minute they had the needles and the yarn out because when a dentist loses a thumb they’re done. So they were stitching the thumb together. The fourth spreader was still banging against the hull so everybody was focused on that. Then we secured the mast, cut the other stuff; this happened unbelievably quickly.” Sayonara sailed by, looked at us. You know how sailors are when you see a mishap of somebody else. First you calculate that they’re [out of the race] and you’re ahead and you get a first and they get a did not finish. So that’s probably in their faces and they just sail by and they’re gone. Larry and his whole crew is gone. We start the engine and the engine doesn’t engage. The pin is broken and we are without engine. And now the boat is tumbling in the waves. The mast is secured, but we can’t move. So there are tenders and we ask for help. We ask the shore base. A tender will be out, but it will take half an hour. A small tender comes, but it can’t take us in the waves, we are too heavy. Here comes Oracle’s tender. Goes around and around. We make all the signals, ‘C’mon pick us up, give us a tow.’ We communicated to them they should not tow us into the harbor, just tow us into the wind so we could clean up the rest and then our tender would come and pick us up and get us home. They didn’t react. They didn’t react. They circled us probably twice. Then I made the official signal. There’s 20 people working and still cleaning up things, I do this here [waves outstretched arms vertically]. They take a video camera and do another round and videotape. When they come the last time from the stern, to take a nice shot from behind. I lowered my pants. I said: ‘If you have to have this on your video, when you go home you should feel s–tty about what you did.’ There is a yacht with 22 people out and we have a serious problem. We have an injury, we don’t know the amount of the injury. But we had blood on the whole boat, we have no engine and we have high waves. They disappear, so we give them some nice America four-letter words and then a big boat came and it took us one and a half hours to get back in the harbor because we had to go slowly the mast banging. We put everything we had between the mast and the hull. So we go home, the race is over, we are done. “Years later I read in the Wall Street Journal that I mooned Larry Ellison. I write to the Wall Street Journal this is not true and they have to redo this. My advisors say: ‘No, don’t get involved with the Wall Street Journal, it’ll only get worse and everybody will pick up the story.’ I made the mistake and gave in. Then it quieted off and then Larry Ellison brought it up in interviews again, two times. In German, when he came to Germany, he made snide comments, one comment was my ass looked so awful that he feared about the mental health of his crew when he sailed by. Another story was that I was so pissed when we lost the race and the World Championships in Sardinia in 1997 in Italy that I came by his boat and mooned him. The day when this should’ve happened, he had already left, because he didn’t race the last race because he was not there. They were moored inside, we were moored outside. We never went by him. So now again I ask my lawyers, ‘Shall I do something?’ and they said, ‘Let it die down.'”I met him in Italy and I said, ‘Larry, why are you doing this?'”‘I’m not doing anything. I don’t know what you’re talking about. You never mooned me. I never saw anything.'”I said, ‘Larry, who is writing this s–t?'”‘I don’t know, I will take care of it.'”And then he did it a third time. So that’s Larry Ellison. Everything has been said. Therefore I would never enter an America’s Cup and sail against him. I do this for fun. What I don’t understand is that he put this in a business context and so I think this is an absolute scandal. And then I ask again my lawyers, ‘I’ll make a statement under oath. I never ever mooned Mr. Larry Ellison, nor his Sayonara crew.’ And isn’t that enough? Is there anybody in the world who believes in me? I have 22 quotes signed by the whole crew, half of them the Black Magic [NZL-32] crew, that it was not Sayonara , it was the tender. Sayonara was long gone. There was no reason. I had nothing with Larry Ellison. He couldn’t help it, he was racing by, he says, ‘Good Bye! Thank you for letting us through.’ I didn’t expect any help from them. But we expected help from any of shore crew. And not taking video. That made me really upset.” - More: Sailboat Racing

- More Racing

Women’s America’s Cup Steps Over The Threshold Life On The Edge As Vendée Leaders Dive South SailGP’s Black Foils Start Season 5 With a Win No Doubts in Dubai For Rebooted US SailGP Team Firecrown Acquires Active Interest Media’s Marine Group St. Petersburg Kicks Off Regatta Series With 5 Class Championships - Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

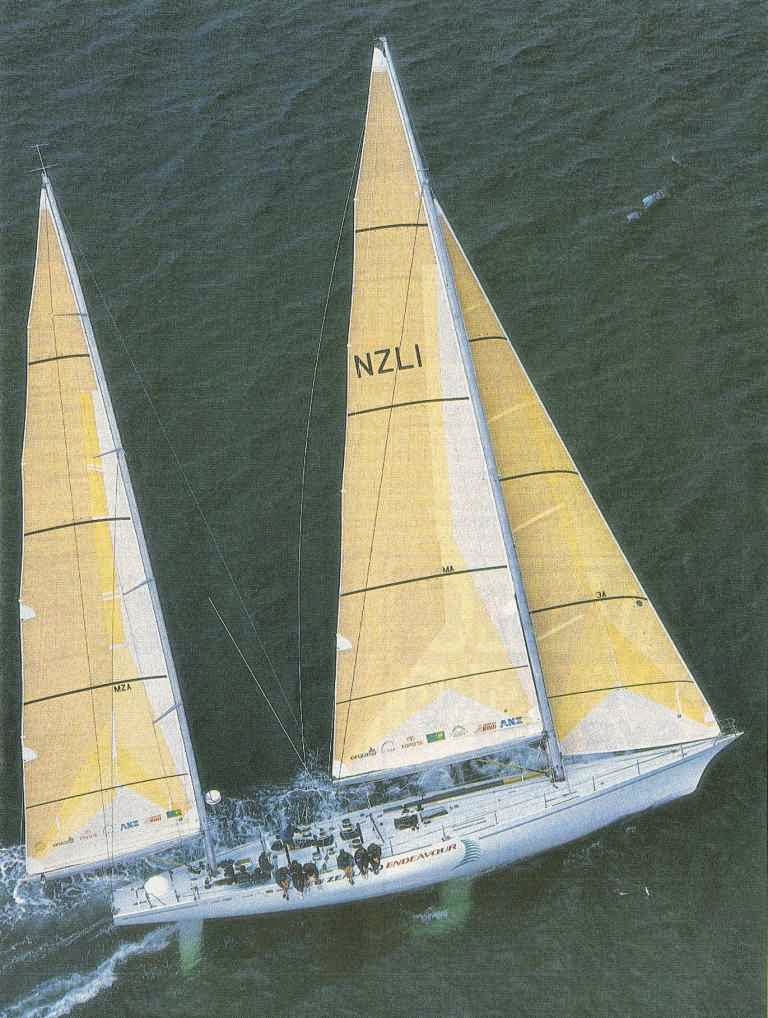

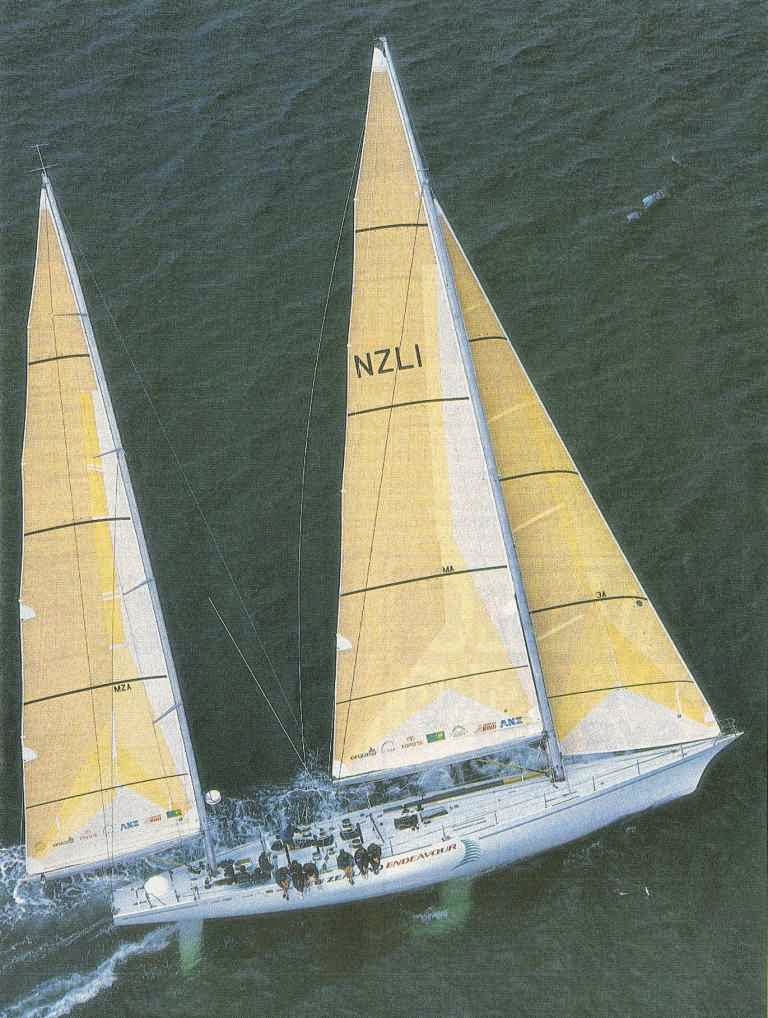

Mike Sanderson: Three decades of racing Maxi’sCourtesy of the International Maxi Association. From New Zealand Endeavour to Bella Mente: Mike Sanderson on his three decades maxi racing. In yacht racing circles he is best known for skippering ABN AMRO One to victory in the 2005-06 Volvo Ocean Race, and more recently in the industry as the new owner of Doyle Sails, but, as a sailor, for almost three decades Mike Sanderson has been involved in more consistently top level maxi racing yacht projects than perhaps anyone. Moose, as he is known, spoke to the International Maxi Association about his trail-blazing career.  There was some consternation when in 1988 a 17-year-old Sanderson quit the top public school he was attending in his native Auckland a year prematurely in order to become a sailmaker. This, he rightly anticipated, would be step one towards his ultimate aim of becoming a professional sailor. His inspiration came through this being the first halcyon era of Kiwi yachting: the Chris Dickson-led Kiwi Magic had proved an exceptional challenge for the 1987 America’s Cup, comfortably winning the round robin stage, while offshore Peter Blake was mounting his Steinlager campaign that would go on to win every leg of the 1989-90 Whitbread Round the World Race. Having been perpetual runner-up to Steinlager with his Fisher & Paykel, skipper Grant Dalton was not going to be outgunned again and for the 1993-94 race entered the ultimate (and final) Whitbread maxi ketch, New Zealand Endeavour . Recommended to Dalton by his former navigator Murray Ross, a 21-year-old Sanderson managed to hitch a ride as a trimmer/driver, in awe at sailing alongside many of his heroes from KZ7 and Steinlager . At the time, the round the world race was still relatively untainted by safety measures such as ice gates or commercial pressures to visit Asia, but uniquely, for anti-aparteid reasons, was the one race to miss Cape Town – instead its second leg was a giant from Punta del Este, Uruguay directly to Fremantle, Australia. As Sanderson recalls: “We ended up really far south with icicles on deck and the wind gear freezing and very early Gore-Tex type wet weather gear which leaked like a sieve. And we broke the mizzen on that leg. We still led for a long time but finally we got mowed down by Merit coming into Fremantle.”  Despite the new spritely water ballasted Whitbread 60s nearly beating them on the water, loudly sounding the death knoll for the IOR maxis, it was nonetheless a fantastic end-of-era experience for the impressionable Sanderson. “We did something like 26 knots, but the maxi ketches were ridiculously contorted slave ships! We had around 23 sails on board, five or six different mizzen staysails alone, so it was a constant peeling frenzy all the way around the world, with guys out on the end of the spinnaker poles, dip pole gybing and some very nice Kevlar panelled sails!” Alongside another Whitbread with Dalton again four years later on the Whitbread 60 Merit Cup when, aged 26, he was watch captain, the late 1990s were an intense period for Sanderson’s maxi yacht sailing. With Dalton he continued on to the relatively short-lived Grand Mistral/Maxi One Design circuit – initially an attempt by Swiss round the world maxi skipper Pierre Fehlmann to set up a one design oceanic racing circuit in identical water ballasted Farr 80s, the fleet eventually owned by Ernesto Bertarelli prior to his America’s Cup involvement. Sanderson sailed on board the all-black Frers 93 Stealth while she was in the USA, training for a transatlantic record attempt that ultimately never happened. At a time when her owner, the ‘King of Italy’, renowned Fiat boss Gianni Agnelli, was regularly on board: “It’s been amazing watching these Ford versus Ferrari documentaries recently and seeing what a legend he was.” He also got a taste of Californian turbo sled competition, competing on board Robert McNeill’s Reichel-Pugh 75 ULDB Zephyrus IV , which not only won but set a course record for the Cape-Rio Race in 2000. Significantly in 1999 he was part of the crew, led by Chris Dickson, on Larry Ellison’s all-conquering Farr 79 ILC maxi Sayonara , consecutive winner of the Maxi Worlds between 1997 and 1999 – also at a time when Ellison was regularly competing. Sayonara was Ellison’s first boat after he had been introduced to Bruce Farr and Geoff Stagg, plus Team New Zealand by David Thompson, a Kiwi sailor living in San Francisco who went to the same gym as Ellison. This was how many of the Kiwi legends such as Brad Butterworth ended up racing with Ellison between their victorious 1995 and 2000 America’s Cups. Aside from her star crew, Sayonara ’s success says Sanderson lay in a very well run program by Bill and Melinda Erkelens, working with the Farr office to optimise her IMS rating from regatta to regatta. It was allegedly while having dinner aboard Ellison’s superyacht Katana , while at Antigua Sailing Week that Team New Zealand’s Tony Rey (aka Trey) first suggested to Ellison that he should get involved in the America’s Cup. “Larry was most put out because lots of our guys went to sail at Oracle, but not Trey, who stayed at Team New Zealand…”  Racing on Sayonara led to Sanderson getting the position of main sheet trimmer on Oracle BMW Racing, Ellison’s first challenge for the America’s Cup in Auckland in 2003. But Sanderson’s most consistent maxi yacht program, which began at this time, is Robert Miller’s Mari-Chas. In 1997, Miller was in the process of graduating up from his Frers 92 Mari-Cha II (subsequently Bristolian) to a new 47m Briand ketch, Mari Cha III . At the time she was in construction at Sensation Yachts in New Zealand and the story goes that Miller’s long term project manager and boat captain Jef d’Etiveaud had phoned North Sails in Auckland and the receptionist had called out to the boss Tom Dodson “I’ve got a guy on the phone who’s building a 47ft ketch”. Believing it to be a more modest craft, Dodson had passed it on to Sanderson as their ‘ketch expert’. “I didn’t say anything to anyone but I got in my car and drove out to Sensation to meet Jef and here, 23 years on, the rest is history!” The Mari Cha campaign was especially attractive for Sanderson as it was both inshore and offshore. Following his Whitbread on Merit Cup, Sanderson and leading Kiwi bowman Richard Meacham, found themselves the lone English speakers, alongside the owner Robert Miller, on Mari-Cha III when she broke the monohull transatlantic record, from New York to the Lizard, in 1998. Given his credentials, despite still only being in his 20s, Sanderson from then on became Mari-Cha ’s racing skipper and he was able to become deeply immersed in the design team that created Miller’s next, even more extreme maxi. While his previous yacht had a full luxury interior, the new 42m long yacht was stripped out, fitted with a canting keel (and a 10 tonne bulb) and rigged as a schooner. At the time of her launch at JMV Industries in 2003, Mari-Cha IV was the world’s longest (and soon to be fastest) racing monohull.  “That was a very cool project,” recalls Sanderson. “One of the key drivers at the time was how big we could build 3DL mainsails – so we had the option of a 100-110ft sloop or a 130-140ft schooner.” Running simulations on the transatlantic record course it became very obvious that longer was faster. Most impressively, just two months after her launch in France, Mari-Cha IV demolished the monohull west to east Transatlantic record setting a time of 6 days 17 hours 52 minutes and 39 seconds (18.2 knots average) that would stand for another 13 years. “The stars aligned for us at every point,” Sanderson recalls. “We had a fantastic crew [including many of the French Vendée Globe and multihull sailor rock stars], the owner had a great time, we didn’t break anything of any substance. All in all it was a roaring success.” During the record she had also set a new monohull 24 hour record of 525 miles, becoming the first monohull to break the 500 mile/day (20.8 knot) barrier – although today monohulls are achieving this sailed singlehanded! Mari-Cha IV ’s collosal size also held other benefits. Sanderson recalls: “If we got caught without being able to peel or if we’d broken something and we had to do a bare-headed change that boat would still happily tick along at 17 or 18 knots while you were getting ready.”  Miller and his crew subsequently went on to win the Rolex Transatlantic Race from New York to the Lizard and on to Cowes in 2005, marking the centenary of the New York Yacht Club’s famous race for the Kaiser’s Cup, won by Charlie Barr and the three masted schooner Atlantic . While Mari-Cha IV has long since sold (now renamed Samurai, she has been detuned and refitted by Royal Huisman with a superyacht interior), Miller, albeit now well into his 80s, continues to race and cruise with his family and his long standing team, including Sanderson, on board Mari-Cha III. The slippery giant ketch received a significant make-over in 2017, which involved adding 3m extra to the main and mizzen masts and fitting square-topped mainsails, EC6 composite rigging and halyard locks. “The boat is now an ORC weapon in my opinion,” says Sanderson. “We were very unlucky not to win the Superyacht Cup in Palma that year.” While Sanderson made a brief foray into the IMOCA 60 class, with a new boat designed by Juan Kouyoumdjian and backed by Andrew Pindar, his greatest achievement as a sailor came when he was recruited to skipper ABN AMRO One , the Dutch-flagged Volvo Open 70 in the 2005-06 Volvo Ocean Race. He recalls: “There was a lot of pressure, but we were also given every opportunity – we wanted for nothing, we had no restrictions on crew, we could train wherever in the world we wanted to, we could build two boats, we had a great sail budget and a great, great bunch of people right from the start.”  ABN AMRO One dominated the 2005-06 Volvo Ocean Race, the first for the new generation Volvo Open 70s, winning six of its nine legs. But it was also a rollercoaster of highs and lows – on the one hand getting married to Emma Richards with his crew all acting as grooms at the Royal Yacht Squadron in Cowes, on the other the sad sad loss of popular Dutch crewman Hans Horrevoets from on board the ABN AMRO ‘youth boat’ during the Transatlantic leg, something which he admits haunts him to this day. In part two of this article – to be published on Monday May 10 th – Sanderson discusses his part in Hap Fauth’s multiple Maxi 72 World Championship winning Bella Mente campaign, his acquisition of Doyle Sails and how he believes the pandemic is going to affect the pro sailing world. (By James Boyd / IMA) https://bit.ly/2WcLUQ6  Inside The Wild World Of Super-Maxi Yacht RacingThe world’s fastest and most advanced sailing seafarers head to the Caribbean to compete in the yachting world equivalent of F1. - Share on Facebook Facebook

- Share on Twitter Twitter

- Share on Pinterest Pinterest

I hit the tarmac in Sint Maarten in the Netherlands Antilles revved up to partake in the yachting world equivalent of Formula One for the weekend. Hopping onto a screaming machine taming the forces of nature to barrel along billionaire style. For it was the St. Maarten Heineken Regatta and I was going racing aboard a super-maxi yacht . Held annually this is one of the highlights of the yacht racing world’s calendar, drawing the best boats and crews from all over the world to pit their machinery and knowhow against each other during a long weekend of hard racing, hard partying and camaraderie—all on one of the most welcoming islands in the Caribbean. The super-maxis are the ultimate racers of the yacht world and are governed by a set of rules which describe them as monohulls of more than 100 feet in length, with a keel and no limit on the number or type of “appendages.” Pure bucket-list stuff, where if you have to ask what it costs you clearly have no idea what you are getting into. At the end of ancient maps, uncharted waters were simply marked with mystical creatures and the notation, “here be dragons.” Well that is where I was headed. And fast. Installed at the newly-opened Morgan Resort & Spa in this Dutch West Indies idyll, I inhaled deeply of the view; and pondered what a view it was, out over turquoise waters and clear blue skies gusting 25-plus knots of wind. For things were about to go super-maxi off the beaches of Sint Maarten, in the form of a ride aboard one of the most legendary racing yachts on the water today—Leopard 3. At a touch over 100 feet, this carbon fiber/Nomex-hulled missile can shoot through the water at over 40 knots when at full tilt downwind. Fully rigged with over 15,000 square feet of thermo-formed carbon composite sails on her 154-foot carbon fiber mast and rigging, she is an extreme machine that has won everything from the Rolex Maxi Cup to Les Voiles de Saint-Tropez, set trans-Atlantic speed records, and carried her racing crew of 20-plus souls to victory across the globe. Designed by the legendary Farr Yacht Designs based out of Annapolis in Maryland, she is wide—22 feet at the widest point of her beam—and perfectly suited for fast offshore racing with more than a few tricks up her sleeve. Her “appendages” include a keel that cants up to 40 degrees, stabilizing her as if 200 extra crew members were sitting on the rail, and twin asymmetric lifting dagger-boards located either side of the mast to perfectly balance the sail forces when racing at full tilt.  The days of ex-NFL linebackers with 22-inch biceps grinding the winches of racing yachts are mostly behind the likes of Leopard 3, which features hydraulic winches, but the combination of almost military discipline and ballet-like choreography among its professional racing team are a delight to behold. The Captain and tactician calling the moves with precision timing, and an otherworldly sense of the wind down to the second, divining increases and decreases in invisible forces as if Merlin himself were aboard as the team trims sail to maximize speed at all moments. The real key to the deployment of this technological wizardry is the team which employs it. As with Formula One, two things are necessary in spades—enormous amounts of money, and enormous amounts of skill and experience on the team. One begets the other, but it also pays for the eye-watering expenses of maintaining the boat and crew in peak condition with every carbon sail, titanium nut and bolt, and carbon fiber piece in optimal race-ready condition. Like life, things wear out, break, and go amiss. I’ve been on boats that have snapped masts, lost sails, hell, almost sank. And for mere mortals if this happens you go bankrupt. But in the world of billionaire yacht-racing, you just Fedex a new carbon fiber mast half way around the world overnight, and have it fitted to keep you racing the next day. I saw Larry Ellison do this at Antigua Race Week one year when his yacht Sayonara snapped its mast—and it says everything you need to know about sailing super-Maxi style. Read This Next Todd Snyder Partners With NFL & Fanatics For Luxe, Limited-Edition Fan Gear Collection The Best American Double-Barrel Whiskeys Of 2024 The Best American Rye Whiskeys Of 2024 ‘Quantum Of Solace’ Star And Former Bond Girl Gemma Arterton Disagrees With Idea Of Gender-Swapping 007: “Isn’t A Female James Bond Like Mary Poppins Being Played By A Man?”By Bounding Into Comics  ‘Qunatum Of Solace’ Star And Former Bond Girl Gemma Arterton Disagrees With Idea Of Gender-Swapping 007: “Isn’t A Female James Bond Like Mary Poppins Being Played By A Man?” Bond Actress Gemma Arterton Slams ‘Outrageous’ Idea For Female James Bond, Calls for Respecting TraditionAdvertisement Supported by PLUS: YACHT RACING -- SYDNEY-TO-HOBART RACE PLUS: YACHT RACING -- SYDNEY-TO-HOBART RACE; Sayonara, the American Favorite, Surges AheadBy Agence France-Presse The American maxi Sayonara was on record pace and building on a lead of six nautical miles as the fleet in the 54th annual Sydney-to-Hobart yacht race emerged today from an overnight battering. Both Sayonara, the 80-foot favorite, and the Australian maxi Brindabella were under the record pace set by Morning Glory in 1996, but the crew of Sayonara had broken clear of its rivals by midday, race organizers said. Damage from the heavy weather overnight forced the retirement of at least nine boats, including Wild Thing and Marchioness, which both suffered damage to their rigging in gale force winds that hit the fleet late yesterday. Both Sayonara and Brindabella entered the often treacherous Bass Strait early today with southwesterly winds forecast to increase to as much as 45 knots. Sayonara is owned by the American billionaire Larry Ellison, who had angered some in the Australian yachting community by predicting his yacht would set a new record. The world maxi champion, Sayonara has been beaten only once since it was launched in 1995 and was the clear favorite before the race began yesterday. A victory by the American yacht would make it the third time in four years that a foreign yacht has won Australia's most prestigious race. The current record for the 630-nautical-mile course from Sydney Harbor to Hobart, on the island of Tasmania, is 2 days 14 hours 7 minutes 10 seconds. It was set in 1996 by the German yacht Morning Glory.  |

COMMENTS

Having been holed up in Holland Michigan since the 2000 Chicago Mackinac Race, Sayonara, Larry Ellison's 80' Maxi is headed home. ... Sayonara was the launching pad for Larry Ellison into the yacht Racing World, his first foray into serious competition. In a conversation with his neighbor, one David Thomson back in 1994, the subject of ...

Ellison also owns the maxi Sayonara, which won the infamous 1998 Sydney-Hobart race that cost the lives of six sailors from other yachts.Sayonara was in such another league that it literally outran a storm of epochal brutality across the Tasman Sea-further proof, if needed, that the rich do indeed lead different lives and play under different rules.

Design #323 ILC Maxi . October 1995. With the Offshore Racing Council's formation of the IMS based ILC MAXI level rating class and the Transpac Yacht Club's announcement that it would use the ILC Maxi as the big boat limit for the 1995 Transpac Race, it was logical that California owner Larry Ellison and his representative David Thomson would commission the design for SAYONARA to sail in the ...

ILC maxi (design № 323), designed in 1994 for Larry Ellison. Some of the many wins in this design include: The Rolex Sydney Hobart (1998), the NYYC Annual Regatta (2000), the Chicago to Mackinac (1998 + 2001) and the Rolex Big Boat Series (1996).

He was a crew member of the winning yacht Sayonara, a 79-foot maxi boat that had sufficient size to survive winds that reached 90 mph and swells as high as 35 feet.

"We had a business meeting and he told me he was building a maxi yacht, must be 1994 or '95. ... "Sayonara was at that point probably 10 boat lengths behind us because we had a nice little ...

Racing on Sayonara led to Sanderson getting the position of main sheet trimmer on Oracle BMW Racing, Ellison's first challenge for the America's Cup in Auckland in 2003.. But Sanderson's most consistent maxi yacht program, which began at this time, is Robert Miller's Mari-Chas. In 1997, Miller was in the process of graduating up from his Frers 92 Mari-Cha II (subsequently Bristolian ...

Sayonara, Larry Ellison's 83 foot Maxi Just north of the Manitous, the three lead boats, Equation, Pied Piper, and Holua sailed into the front to the east of the Low and after a brief period of slogging upwind, started to "power beat" with sheets eased to Grey's Reef in a strong ESE breeze of 12 to 14 knots.

For it was the St. Maarten Heineken Regatta and I was going racing aboard a super-maxi yacht. ... I saw Larry Ellison do this at Antigua Race Week one year when his yacht Sayonara snapped its mast ...

The world maxi champion, Sayonara has been beaten only once since it was launched in 1995 and was the clear favorite before the race began yesterday. A victory by the American yacht would make it ...