Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Video: 6 of the best heavy weather sailing videos

- Harriett Ferris

- June 18, 2017

Watch our pick of the most dramatic heavy weather videos

This first video of heavy weather sailing is our from our Storm Sailing Series with Skip Novak . It was probably the most ambitious project Yachting World has ever undertaken: to head for Cape Horn with high latitudes doyen Skip Novak to make a series on Storm Sailing Techniques . Here is one of our most popular videos, rounding Cape Horn in Storm Force 10 conditions…

Hallberg Rassy are known for being heavy, sturdy, seaworthy boats. This video shows Hallberg Rassy 48 Elysium in heavy weather off Cape Gris Nez, northern France in 2014. The yacht seems to be handling well, able to use a Raymarine lineair 7000 autopilot depsite the conditions.

This compilation is from the BT Global Challenge round the world race, a crewed race westabout the prevailing winds in one-design steel 72-footers. It took amateur crews upwind through the Southern Ocean from Cape Horn to New Zealand and from Australia to Cape Town. This footage shows some of the weather they experienced and what the crews endured – and watch out for some footage of the race leaders fighting it out under trysail during a severe storm in the Cook Strait in New Zealand.

Single-handed sailor Berthold Hinrichs sailing in Hinlopenstretet. It is the 150km long strait between Spitsbergen and Nordaustlandet in Svalbard, Norway and can be difficult to pass because of pack ice.

A fun compilation video of sailing in strong breeze including 2 wipeouts, 1 dismasting and 1 guy going for a swim…

Our last example comes from popular YouTube channel Sailing SV Delos , as the crew tackle a 50-knot gale on the crossing to Madagascar. Skip to 8:00 for the stormy stuff:

If you enjoyed this….

Yachting World is the foremost international magazine for bluewater cruisers and offshore sailors. Every month we have practical features to help you plan and prepare to realise your sailing dreams. Build your knowledge month by month with a subscription delivered to your door – and at a discount to the cover price. S ee our latest offers now.

A Complete Guide To Sailing In A Storm

Sailing in a storm can be a challenging experience but with the right preparation and techniques, it can be navigated safely in most instances.

While it's best to avoid storms when sailing, there are times when storms cannot be avoided.

To sail in a storm:

- Prepare the sailboat for a storm

- Monitor the weather conditions

- Adjust the sailboat to stabilize the vessel in the storm

- Maintain communication with the coast guard

The number one priority when sailing in a storm is safely navigating through the water during these bad weather conditions.

1. Prepare The Sailboat For A Storm

The first step of sailing in a storm is to prepare the sailboat for storm weather conditions.

To prepare a sailboat for a storm:

- Check the rigging & sails : Assess the rigging and sails overall condition. Ensure they are in full working order with no issues with maneuverability or rips in the sails. There should be a storm sail onboard too in preparation for sailing in the storm

- Ensure safety equipment is onboard : Ensure there are liferafts, life jackets for everyone onboard, life buoys, heaving lines, sailing jackets, flashlights, flares, VHF radios, chartplotter/GPS, first aid kits, and fire extinguishers

- Remove the boat canvas/bimini top : In preparation for sailing in a storm, remove the boat canvas/bimini top to prevent it from getting damaged or destroyed or causing injury to passengers onboard

- Ensure loose items are tied down : Any loose items like lines on the deck should be tied down and secured before sailing in a storm. Loose items can become dislodged and damaged or cause injury to passengers onboard if they are not secured during a storm

- Ensure the sailboat's engine is in great condition : Ensure the sailboat's motor is in perfect condition with sufficient oil and fuel to operate during the storm

Preparing the sailboat for a storm will take approximately 30 minutes to complete. This timeframe will vary depending on the size of the vessel and the amount of equipment needed to be purchased and installed onboard.

In preparing for sailing in a storm, there is certain sailboat equipment needed. The equipment needed for sailing in a storm includes a storm sail, heaving lines, sailing jackets, life jackets, life buoys, liferafts, first aid kit, Chartplotter/GPS, fire extinguishers, VHF radio, and flares.

The benefits of preparing the sailboat for a storm are a sailor will be prepared for any issues caused by the storm and a sailor will have the necessary safety equipment to help keep everyone onboard safe during the storm.

One downside of preparing the sailboat for a storm is it can be costly (over $500) especially if the sailor does not have all the right equipment needed to withstand the stormy weather. However, this is a small downside.

2. Monitor The Weather Conditions

The second step of sailing in a storm is to monitor the weather conditions regularly.

To monitor the weather conditions:

- Connect to the VHF radio weather channel : Connect to channel 16 on the VHF radio as this channel provides storm warnings and urgent marine information for boaters

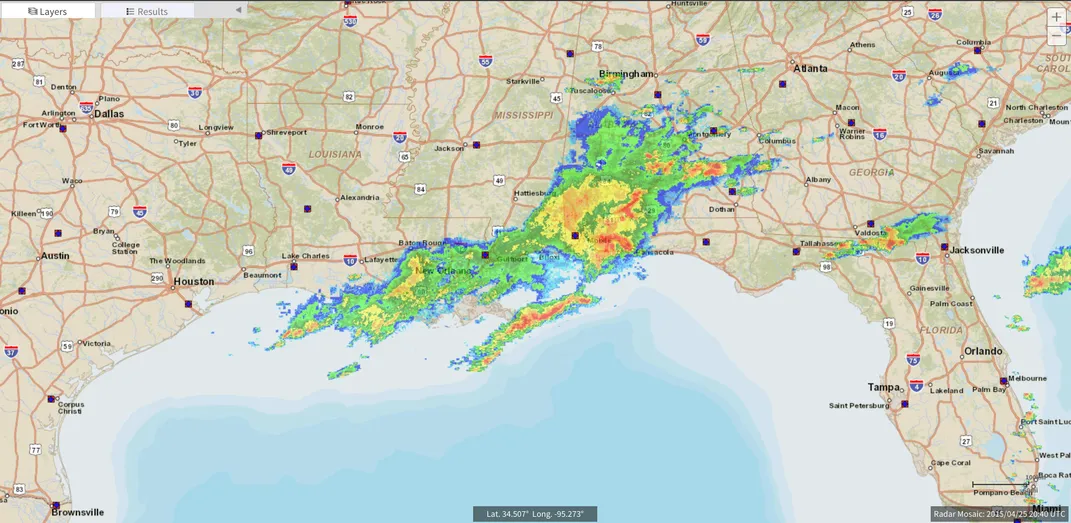

- Use a chartplotter : Modern chartplotters will have marine weather data for boaters to monitor the weather conditions and check windspeeds, rainfall levels, wave height and other relevant marine weather data

- Check a marine weather forecast provider website : If you have internet access on the sailing trip, connect to a marine weather provider for marine weather forecast information in your area

In sailing, weather conditions are considered a storm when the wind speed is 28 knots or higher and the wave heights are 8ft or higher. Other characteristics of stormy weather when sailing is poor visibility with visibility ranges of under half a mile (0.8km or less) and heavy rain with a precipitation rate of at least 0.1 inches (2.5 millimeters) per hour.

It can take approximately 3 to 6 hours for a storm to fully develop when sailing. However, for larger storms, it can take over 2 days for the storm to fully develop.

Monitoring the weather should be done every 20 minutes when sailing in a storm to get up-to-date information on potential nearby locations with better weather to sail to.

The benefit of regularly monitoring the weather conditions is a sailor will be more prepared for the weather that lies ahead and the sailor will be able to make adjustments to their sailing route to help avoid the bad weather.

3. Adjust The Sailboat To Stabilize The Vessel

The third step of sailing in a storm is to adjust the sailboat to stabilize the vessel.

When sailing through the storm, reef the sails to reduce the stress and load on the mast and sails, attach the storm sails, turn the vessel until the wave and wind direction are blowing from the stern of the sailboat, i.e. the wind is blowing downwind. Carefully tack the sailboat slowly until the boat is in the downwind position. Pointing the sailboat downwind is not recommended if the sailboat is near land as it could cause the boat to run into the land.

Alternatively, if the storm is very bad, sailors can perform a "heaving to" storm sailing maneuver.

To perform the heave-to storm sailing maneuver:

- Turn the bow of the boat into the wind : This involves turning the sailboat so that the bow faces into the wind. This will cause the boat to lose forward momentum and begin to drift backward

- Adjust the sails : Depending on the size and configuration of your boat, you may need to adjust the sails in different ways. In general, you will want to position the sails so that they are catching less wind and are working against each other. This will help to slow the boat's drift and keep it from moving too quickly

- Adjust the rudder : You may need to adjust the rudder to keep the boat from turning too far or too fast. In general, you will want to angle the rudder slightly to one side to counteract the wind and keep the boat on a stable course

- Monitor the boat's drift : Once you have heaved-to, you will need to monitor the boat's drift and make small adjustments as needed to maintain your position. This may involve adjusting the sails, rudder, or other factors as conditions change

The heaving to maneuver is used to reduce a sailboat's speed and maintain a stationary position. This is often done in rough weather to provide the crew with a stable platform to work from or to wait out a storm.

This sailing maneuver will adjust the sailboat and should stabilize the vessel in the storm.

The benefits of adjusting the sailboat position in a storm are it will help to stabilize the boat, it will improve safety, it will reduce the crew's fatigue as the crew will not be operating with a boat at higher speeds, it will help maintain control of the sailboat, and it will reduce stress on the sailboat and the rigging system.

Depending on the size of the sailboat, how bad the weather conditions are, and a sailor's experience level, adjusting the sailboat to stabilize it in the storm should take approximately 10 minutes to complete.

4. Maintain Communication With The Coast Guard

The fourth step of sailing in a storm is to maintain communication with the coast guard.

This is particularly important if the storm is over Beaufort Force 7 when sailing is much harder.

To maintain communication with the coast guard during a storm:

- Understand the important VHF channels : During sailing in a storm, be aware of VHF international channel 16 (156.800 MHz) which is for sending distress signals

- Ensure there are coast guard contact details on your phone : Put the local coast guard contact details into your phone. These contact details are not substitutes for using the VHF channel 16 distress signal or dialing 911. These contact details should only be contacted if all else fails

Contacting the coast guard takes less than 1 minute to complete and they are fast to respond in case of an emergency caused by the storm.

The benefits of maintaining communication with the coast guard during a storm are it will help improve safety, the coast guard will be able to provide real-time alerts, and it will provide navigation assistance as the coast guard has access to the latest navigation technology and can guide you through the storm's hazardous areas such as shallow waters or areas with a strong current.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sailing In A Storm

Below are the most commonly asked questions about sailing in a storm.

What Should You Do If You're Caught Sailing In A Storm With Your Boat?

if you're caught sailing in a storm with your boat, you should reef the sails, attach the storm sails and tack the vessel slowly until the wave and wind direction are blowing from the stern of the sailboat.

Should You Drop An Anchor When Sailing In A Storm?

Dropping an anchor can be a useful technique to help keep a boat steady during a storm. However, whether or not to drop an anchor depends on a variety of factors including the size and type of the boat, the severity of the storm, the water depth, and the type of bottom (i.e., mud, sand, or rock).

If you are in a smaller boat that is being pushed around by the waves, dropping an anchor can help keep the boat oriented in a particular direction, reducing the boat's drift. Additionally, it can help reduce the risk of capsizing or being thrown onto a rocky shore.

However, if the storm is very severe with high winds and waves, the anchor may not be enough to hold the boat in place, and it may put undue stress on the anchor and the boat's attachment points. In such a case, it is usually better to try to navigate to a sheltered area or to deploy sea anchors that can help reduce the boat's drift.

It is also essential to be careful when anchoring in a storm as it can be challenging to set the anchor correctly and the wind and waves can cause the anchor to drag.

Is It Safe To Sail In A Storm?

Sailing in a storm should be avoided due to the lack of safety. However, experienced sailors can sail in storms up to Beaufort Force 7 if required. Beaufort Force 8 and higher storms are extremely dangerous to sail in and should be avoided at all costs.

How Do You Improve Safety When Sailing In A Storm?

To improve safety when sailing in a storm, wear a life jacket, hook everyone onboard up to a safety line or harness so they don't fall overboard, reef the sail to improve the sailboat's stability, and understand where all the safety equipment is onboard and how to operate it in case of an emergency.

What Type Of Storm Should Not Be Sailed In?

A sailor should not sail in any storm but especially a storm from Beaufort Force 8 to Beaufort Force 12 as it is considered to be too dangerous.

Can You Sail Through A Hurricane?

While sailors have successfully sailed through hurricanes in the past, sailing through a hurricane should be avoided at all costs. Sailing in hurricane weather is too dangerous and could result in loss of life.

What Are The Benefits Of Sailing In A Storm?

The benefits of sailing in a storm are:

- Improves sailing skills : Sailing in a storm will force sailors to improve their sailing skills and increase their ability to handle rough seas

- Exciting experience : For some sailors, the thrill of navigating through a storm can be an exhilarating experience that they enjoy. The adrenaline rush and sense of accomplishment of successfully sailing through a storm can be incredibly rewarding

- Greater appreciation for the power of nature : Sailing in a storm can provide a unique perspective on the power of nature. It can be humbling and awe-inspiring to witness the raw force of the wind and waves and this can lead to a greater appreciation for the natural world

It's important to note that these potential benefits should never come at the expense of safety. For the majority of sailors, it is smarter to avoid sailing in a storm and instead wait for the bad weather to pass.

What Are The Risks Of Sailing In A Storm?

The risks of sailing in a storm are:

- Boat sinking/capsizing : With high winds over 28 knots and waves and swells at heights over 8ft, there is a risk of the sailboat capsizing and sinking

- People drowning : High winds and high waves during a storm can cause people onboard to fall overboard and drown

- Loss of communication : Bad storm weather can cause the sailboat's communication system to stop working making it much harder to signal for help if needed

- Boat damage : Storm weather can damage the boat including the sails, mast, rigging system, lines, Bimini top, etc.

- Poor visibility : Sea spray, large waves over 8ft, and heavy winds over 28 knots can reduce the visibility to under 500 meters in some instances making it difficult for navigation

- People being injured : People onboard can get injured due to the increase and sharp movements caused by the storm

What Should Be Avoided When Sailing In A Storm?

When sailing in a storm, avoid:

- Getting caught sailing in the storm in the first place : Ideally, a sailor should avoid sailing in the storm in the first place by checking the weather radar and instead wait for the weather to clear before continuing their sailing trip

- Increasing the sail area : Increasing the sail area in a storm should be avoided as it can cause the sailboat to become more unstable and increase the risk of capsizing

- Not wearing a life jacket : Life jackets should be worn at all times when sailing but especially during a storm. Avoid not wearing a life jacket in a storm as there is no protection if someone falls overboard

- Not wearing the appropriate gear to stay dry : Sailors should avoid not wearing the appropriate foul weather gear to stay dry when sailing in a storm

- Not connecting the crew to safety lines/harness : When sailing in a storm, all crew on the boat deck should be

- Not understanding the safety equipment : Sailors should avoid not understanding the safety equipment onboard

How Do You Avoid Sailing In A Storm?

To avoid sailing in a storm, check the weather forecast regularly when going on a sailing trip to know when and where not to sail as the weather gets worse in these areas. If a sailing trip involves passing through a storm, wait in an area where there is no storm until the weather clears up in the storm area before continuing on the voyage.

What Are The Best Sailboats For Sailing In A Storm?

The best sailboats for sailing in a storm are the Nordic 40, Hallberg-Rassy 48, and the Outremer 55.

What Are The Worst Sailboats For Sailing In A Storm?

The worst sailboats for sailing in a storm are sailing dinghies as they offer little protection from the dangers of stormy weather.

What Is The Best Sized Sailboat For Sailing In A Storm?

The best-sized sailboats to sail in a storm are sailboats sized 30ft. and longer.

What Is The Worst Sized Sailboat For Sailing In A Storm?

The worst-sized sailboats to sail in a storm are sailboats sized under 30ft. as it is more difficult to handle rough weather and choppy waves in these boats.

The Worldwide Leader in Sailmaking

- Sail Care & Repair

- Sailing Gear

- Sail Finder

- Custom Sails

- One Design Sails

- Flying Sails

- New Sail Quote

- 3Di Technology

- Helix Technology

- Sail Design

- NPL RENEW Sustainable Sailcloth

- Sailcloth & Material Guide

- Polo Shirts

- Sweaters & Cardigans

- Sweatshirts & Hoodies

- Accessories

- Mid & Baselayers

- Deckwear & Footwear

- Luggage & Accessories

- Spring Summer '24

- Sailor Jackets

- Maserati X North Sails

- NS x Slowear

- Sailor Jacket

- Sustainability

- North Sails Blog

- Sail Like A Girl

- Icon Sailor Jacket

- Our Locations

- North SUP Boards

- North Foils

- North Kiteboarding

- North Windsurfing

SAIL FINDER

SAILING GEAR

COLLECTIONS & COLLAB

COLLECTIONS

WE ARE NORTH SAILS

ACTION SPORTS

Popular Search Terms

Collections

Sorry, no results for ""

How To Sail Safely Through a Storm

How to sail safely through a storm, tips and tricks to help you get home safe.

Compared to the quick response and sudden nature of a squall , sailing through a storm in open water is an endurance contest. In addition to big wind, you’ll have to deal with big waves and crew fatigue.

Sailing in Waves

Sailing in big waves is a test of seamanship and steering, which is why you should put your best driver on the helm. Experienced dinghy sailors often are very good at heavy air steering, because they see “survival” weather more often than most cruisers.

Avoid sailing on a reach across tall breaking waves; they can roll a boat over. When sailing close-hauled in waves, aim toward flat spots while keeping speed up so you can steer. To reduce the chance of a wave washing across the deck, tack in relatively smooth water. A cubic foot of water weighs 64 pounds, so a wave can bring many hundreds of pounds of water across the deck.

Sailing on a run or broad reach in big waves is exhilarating, but be careful not to broach and bring the boat beam-to a breaker. Rig a preventer to hold the boom out.

Storm Sails

If reefing isn’t enough to reduce power, it’s time to dig out your storm sails — the storm trysail and storm jib. They may seem tiny, but since wind force rises exponentially, they’re the right size for a really big blow. Storm trysails are usually trimmed to the rail, but some modern ones are set on the boom. The storm jib should be set just forward of the mast to keep the sail plan’s center of effort near the boat’s center of lateral resistance. This helps keep the boat in balance.

Storm Strategy

The first decision before an approaching storm is the toughest: Run for cover, or head out to open water for sea room? With modern forecasting, a true storm will rarely arrive unannounced, but as you venture further offshore the chances of being caught out increase. While running for cover would seem the preferred choice, the danger lies in being caught in the storm, close to shore, with no room to maneuver or run off.

Two classic storm strategies are to try to keep away from land so you’re not blown up on shore, and to sail away from the storm’s path — especially its “dangerous semicircle,” which is its right side as it advances.

Storm Tactics

Storm tactics help you handle a storm once you’re in it. There are several proven choices, all of which aim to reduce the strain and motion by pointing one of the boat’s ends (either bow or stern) toward the waves. No one tactic will work best for all boats in all conditions.

Sail under storm jib and deeply reefed mainsail or storm trysail. This approach provides the most control. Sails give you the power to steer and control your boat in the waves.

Run before the storm with the stern toward the waves, perhaps towing a drogue to slow the boat. This tactic requires a lot of sea room, and the boat must be steered actively. Another concern is that you will remain in front of an approaching storm, rather than sailing out of its path.

Heave-to on a close reach with the jib trimmed to windward. Heaving-to can be an excellent heavy weather tactic, though some boats fare better than others.

Deploy a sea anchor while hove-to or under bare poles. A sea anchor is a small parachute set at the end of a line off the bow. A sea anchor helps keep the bow up into the waves so the boat won’t end up beam to the seas. One concern is the load on the rudder as waves push the boat aft.

Another alternative is lying ahull, simply sitting with sails down. This passive alternative is less reliable than the other tactics, as you lose the ability to control your angle to the waves and may end up beam to the seas. Furthermore, the motion of the boat rolling in the waves without the benefit of sails can be debilitating.

Want to order a storm trysail or storm jib for your boat? Contact a North Sails Expert here .

How to Heave-To

Wouldn’t it be great if, during a heavy air sail, you could just take a break, and relax for a bit? Imagine a short respite from the relentless pitching and pounding: a chance to rest, take a meal, or check over the boat in relative tranquility. Well, you can. The lost art of heaving-to allows you to “park” in open water.

To heave-to, trim the jib aback (i.e., to the wrong side), trim the main in hard, and lash the helm so the boat will head up once it gains steerageway. As the jib tries to push the bow down, the bow turns off the wind and the main fills, moving the boat forward. Once the boat begins to make headway, the lashed helm turns the boat toward the wind again. As the main goes soft the jib once again takes over, pushing the bow down. The main refills, and the rudder pushes the bow into the wind again.

The boat won’t actually stop. It will lie about 60 degrees off the wind, sailing at 1 or 2 knots, and making significant leeway (sliding to leeward). The motion will be much less than under sail, and dramatically more stable and pleasant than dropping all sails and lying ahull. You will also be using up less sea room than if you run before the storm at great speed.

Achieving this balance will require some fine tuning, depending on the wind strength, your boat design, and the sails you are flying. Also, fin-keeled boats do not heave to as well as more traditional designs.

In storm seas, some boats will require a sea anchor off the bow to help hold the boat up into the waves while hove-to.

Alternate Storm Strategy: Don’t Go

If conditions are wrong, or are forecast to worsen, don’t go. If you can avoid the storm, then do so.

If you’re at home, stay there. If you’re mid-cruise, button up the boat, make sure your anchor or mooring or dock lines are secure, and then read a book or play cards. Relax. Enjoy the time with your shipmates. Study the pile of Owners’ Manuals you’ve accumulated with each piece of new gear. Tinker with boat projects.

Put some soup on the stove, and check on deck every so often to make sure the boat is secure. Shake your head as you return below, and remark, “My oh my, is it nasty out there.”

If your boat is threatened by a tropical storm or hurricane, strip all excess gear from the deck, double up all docking or mooring lines, protect those lines from chafe, and get off. Don’t risk your life to save your boat.

Misery and Danger

Although everyone will remember it differently years later, a long, wet, cold sail through a storm can be miserable. As the skipper, you need to make the best of it: watch over your crew, offer relief or help to those who need it, and speak a few words of encouragement to all. “This is miserable, but it will end.”

Take the time to marvel at the forces of nature, and at your ability to carry on in the midst of the storm. Few people get to experience the full fury of a storm. It may not be pleasant, but it is memorable.

While misery and discomfort can eventually lead to fatigue, diminished performance, and even danger, do not mistake one for the other. Distinguish in your own mind the difference between misery and danger. Don’t attempt a dangerous harbor entrance to escape misery; that would compromise the safety of the boat and crew, just to avoid a little discomfort.

Interested in a new sail quote or have questions about your sails? Fill out our Request a Quote form below and you will receive a reply from a North sail expert in your area.

REQUEST A QUOTE

FEATURED STORIES

How to care for your foul weather gear.

27 February

GITANA TEAM WINS INAUGURAL ARKEA ULTIM CHALLENGE

Npl renew faq.

- Refresh page

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

Storm Tactics for Heavy Weather Sailing

- By Bill Gladstone

- Updated: November 15, 2021

Storm tactics can be roughly defined as the ways to handle a storm once you’re in it. There are several proven choices, all of which intend to keep either the bow or stern pointing toward the waves. No one tactic will work best for all sailboats in all conditions. As skipper, it will be up to you to consider the best approach for your vessel, procure the right equipment, and practice with it before it’s needed.

Here we look at some active storm options that might work when conditions are still manageable and you want to actively control and steer the boat. Crew fatigue is a serious consideration when using active tactics.

Forereaching

Although not often mentioned as a tactic, it can be highly effective for combating brief squalls or moderate-duration storms. Here’s how to set up your boat for forereaching: Roll the jib away (especially if you have a large roller-furler genoa set); reef the main down to the second or third reef position; and sail on a closehauled course, concentrating on keeping the boat flat. It will be a comfortable ride, everyone will be relatively happy, and you will be making 2 to 3 knots on a close reach. Check your course over ground because increased leeway will cause your track to be much lower. This is a possibly useful tactic to claw off a lee shore. Note that not all boats will be at ease forereaching, so you’d better experiment with it ahead of time. Catamarans in particular will lurch and demonstrate much-increased leeway.

Motorsailing

Sometimes it’s necessary from a time or safety perspective to stow the jib and fire up the iron genny instead. Motorsailing lets you point high and make progress to windward. Motoring with no sails will not work well (or at all, in some cases), particularly in big seas, but a reefed mainsail will provide lateral stability and extra power. Trim the main, head up high enough to control your angle of heel, set the autopilot, and keep a lookout. Fuel consumption makes this a short-term option.

Here’s a tip: Make sure cooling water is pumping through the engine. On some sailboats, the water intake lifts out of the water when heeled. A further difficulty is that the pitching boat might stir sediment off the bottom of the fuel tank, which can, in turn, clog the fuel filter.

Running off and drogues

Sailing under storm jib and a deeply reefed mainsail or storm trysail provides the most control. If you don’t have storm sails, a reefed jib will give you the power to steer and control your boat in the waves. The boat must be steered actively to maintain control because no autopilot will be able to do this.

If excessive speed is a problem and steering becomes difficult, towing a drogue will slow the boat. A retrieval line should be set from the head of the drogue for when it is time to bring it back on board. If you don’t have a drogue, trailing warps might help slow the boat.

In a storm of longer duration, or when conditions become otherwise unmanageable, the situation might call for a skipper to consider passive storm tactics. When you are exhausted and you just want to quiet down the boat and maybe get some rest, there are other boathandling options available, depending on the sea state and the equipment you have onboard.

Heaving to can be an excellent heavy-weather tactic, though some boats fare better than others. Wouldn’t it be great if during a heavy-weather episode you could just slow everything way down? Imagine a short respite with a reduced amount of motion from the relentless pitching and pounding. A chance to regroup, make a meal, or check over the boat. Well, you can.

Heaving to allows you to “park” in open water. Hove-to trim has the jib trimmed aback (that is, to the wrong side), the reefed main eased, and the helm lashed down to leeward. The easiest way to do this is to trim the jib sheet hard and then tack the boat, leaving the sheet in place. Trimmed this way, the jib pushes the bow down. As the bow turns off the wind, the main fills and the boat moves forward. With the helm lashed down, the rudder turns the boat toward the wind. As the main goes soft, the jib once again takes over, pushing the bow down. The main refills, and the rudder pushes the bow into the wind again.

RELATED: Safety at Sea: Mental Preparations Contribute to Positive Outcomes

Achieving this balance will require some fine-tuning, depending on the wind strength, your boat design and the sails you have. You might, for example, need to furl the jib most of the way in to match the wind strength. Trimming the main will ensure that the bow is at an angle to the waves, ideally pointing 40 to 60 degrees off. Modern fin-keeled boats do not heave to as well as more-traditional full-keel designs.

When hove to, the boat won’t actually stop. It will lie, as noted, about 40 to 60 degrees off the wind, sailing at 1 or 2 knots, and making leeway (sliding to leeward). Beware of chafe. When hove to, the jib’s clew or sheet will be up against the shroud and might experience wear damage. Monitor this regularly, and change the position of the sheet occasionally. You might not want to heave to for an extended time.

Deploying a sea anchor

A sea anchor is a small parachute deployed on a line off the bow. A sea anchor helps keep the bow pointed up into the waves so the boat won’t end up beam to the seas. Light displacement boats will pitch violently in high seas, and chafe and damage might occur to the bow, so setting up a bridle and leading it aft through a snatch block will allow the boat to lie at an angle to the waves, providing a more comfortable ride. A big concern when using a sea anchor is the load on the rudder as the waves slam the boat backward. Chafe on the sea-anchor bridle is another big factor, so the bridle must be tended regularly.

Remember, if you and your vessel are caught out in heavy-weather conditions, as a skipper, you must show leadership by setting an example, watching over your crew, offering relief and help to those who need it, and giving encouragement. Remember too, discomfort and fear can lead to fatigue, diminished performance, and poor decision-making. Don’t compromise the safety of the boat and crew to escape discomfort.

Few people get to experience the full fury of a storm. Advances in weather forecasting, routing and communications greatly improve your odds of avoiding heavy weather at sea, but you’re likely to experience it at some point, so think ahead of time about the tactics and tools available to keep your crew and vessel safe.

Heavy weather might not be pleasant, but it is certainly memorable, and it will make you a better sailor. Take the time to marvel at the forces of nature; realize that the boat is stronger than you think.

Happy sailing, and may all your storms be little ones!

This story is an edited excerpt from the American Sailing Association’s recently released manual, Advanced Cruising & Seamanship , by Bill Gladstone, produced in collaboration with North U. It has been edited for design purposes and style. You can find out more at asa.com.

- More: Anchoring , How To , print nov 2021 , safety at sea , seamanship

- More How To

3 Clutch Sails For Peak Performance

It’s Time to Rethink Your Ditch Kit

8 Ways to Prevent Seasickness

How To De-Winterize Your Diesel Engine

Kirsten Neuschäfer Receives CCA Blue Water Medal

2024 Regata del Sol al Sol Registration Closing Soon

US Sailing Honors Bob Johnstone

Bitter End Expands Watersports Program

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

What to Do When Sailing in a Storm: The Complete Guide

It’s your worst nightmare come to life. You’re sailing along in perfectly calm weather when suddenly, the skies gray, thunder booms in the distance and the waves get choppy. Even if you never end up in such a scenario, it’s still a good idea to be ready just in case. What should you do when sailing in a storm?

To stay safe on your sailboat in stormy conditions, remember these tips:

- Make a storm preparedness plan before you venture out

- Don’t freak out, especially when you’re sailing with other people

- Put on your life jacket if you’re not already wearing it and tell your crew to do the same

- Learn how to recognize a storm

- Seek a path that avoids the storm

- Lie ahull, in which you ride out the storm with the sail down

- Use your storm sails to maintain control and steering through rough conditions

- Heave-to, in which you trim your jib and then the main while lashing your helm for steerageway

- Check the weather forecast to avoid future dangers

In this in-depth, complete guide, we’ll walk you through all the above points in much greater detail. Let’s get started.

Sailing in a Storm? 9 Tips for Safe Travels

Have a storm preparedness plan at the ready.

As a sailor, you have to anticipate every possible scenario you might encounter on your boat, even the most unlikely and awful ones. Having a plan to get out of such situations gives you peace of mind. You’ll also have a set of steps to act on so you can hop right to it when trouble comes.

If you often sail with a group of others, sit down with your crew and come up with a storm preparedness plan. You might ask some crew members to man the back of your sailboat and others the front, or someone might unleash the storm sails and others the luff. Whatever it is you want to do on your sailboat, make a plan.

Having a storm preparedness plan doesn’t mean you can’t ever deviate from it. In some situations, it may be more appropriate to heave-to or sail away from the storm, and if so, that’s what you should do.

If this is your first storm aboard a boat, then it’s natural to feel nervous and very unsettled. That’s to be expected. Even seasoned sailors aren’t particularly comfortable handling storms, but they do what they have to.

If you’re captaining a crew especially, you must maintain your poker face. Internally, you can feel turmoil, but outside, you must be stoic, calm, and ready to tackle anything. Even if you’re by yourself, freaking out does nothing but misguide your energy towards your panic. You could also get yourself so worked up that you can’t think straight, causing you to make critical mistakes.

Remember the storm preparedness plan you came up with. Begin completing steps per that plan. Once that starts coming together for you, you should surely calm down.

Besides feeling panicky, make sure to prevent discord among your crew members. They may have agreed to work certain stations when you created your storm preparedness plan, but now that the time has come to actually enact the plan, some crew members might get annoyed or argumentative about their assigned tasks.

Remind your crew that everyone’s lives are at risk until you can get to safety. That should help them recall that there are more important things to worry about right now than who gets to do which task.

Wear Your Life Jacket

Make sure that when drawing up your storm preparedness plan that you remember to include life jackets in there somewhere. There should be enough life jackets for yourself as well as anyone else you have onboard your sailboat.

Not all life jackets are made the same. The U.S. Coast Guard approves of several types or classes of life jacket.

For potential sailing emergencies, we’d recommend Type I, or offshore life jackets. These are ideal when riding in remote waters, rougher seas, and open ocean when you may be stranded for a while. The reflective tape and eye-catching color grab attention. Also, if you or a crew member were to become unconscious after a storm-related boating accident, a Type I life jacket would turn you over so your face is up and out of the water.

You might also invest in a Type II life jacket, which is a near-shore vest. Don these life jackets if riding in inland waters where the conditions are calm and you may be rescued fast. You won’t necessarily be flipped up by your life vest if it’s a Type II, so all your crew members must be conscious when wearing this life jacket.

Know How to Recognize a Storm

You’re no weatherperson, but if you’re a trained sailor, then you should have a knack for predicting storms. Well, predicting maybe isn’t the right word, as you’re using your senses to gauge your surroundings and determine when a weather event may come.

How do you do that? Here are some signs that a thunderstorm could soon roll in on the water:

- The cirrus clouds travel quickly. If you don’t know, cirrus clouds are the shorter, singular clouds that have edges like hair. These clouds are also always at a higher altitude.

- The moon or sun develops a halo around it. This is a sign of humidity, which is typically a predictor of a storm. Look at the brightness of the halo to get a feel for what kind of weather you’re expecting. If the halo is dimmer, the storm won’t be that bad, but a bright halo indicates very inclement weather ahead.

- Look at the birds in the sky, especially the puffins, tropic birds, cormorants, frigate birds, sea ducks, and gulls. Are they all moving away from the sea towards the shoreline? That’s happening for a reason. A storm is imminent.

- Invest in a barometer, a weather tool that tracks your air pressure. If the barometer suddenly gives you a low reading, then the air pressure likely decreased because of an impending storm.

Move from the Storm If You Can

Now that you know a storm is on its way, you have some decision-making to do, and fast. You can either head towards the open ocean or towards shore. Which choice is the smarter one will vary depending on how far you are from the shoreline and the storm. If the shore is 100 miles away but the storm is 25 miles, then veering from it towards open ocean is your smartest bet.

If you have your heart set on getting to shore, make sure you have a clear path in that direction that doesn’t intersect with the storm. If your sailboat gets gripped by tough winds or hard waves, it could catapult into the shoreline, causing massive damage. Sometimes, it’s better not to risk it.

If Not, Lie Ahull

You can’t always avoid or maneuver away from the storm, especially if it comes on suddenly and you weren’t gauging the weather using the tips above. If not, then add the next three tactics to your storm preparedness plan as a Plan B, C, and D.

Lying ahull means you and your crew undo all the sails and lay them flat against your boat. This will prevent the wind from wrestling you in an unintended direction. Otherwise, you just sit and wait for the storm to pass.

Just because your sails are down does not mean your sailboat can’t capsize or that you’re in total control. You’re still at risk, so you should choose when you want to lie ahull strategically. If you’re expecting a day of moderate yet frequent storms, then lying ahull is a good idea. You and your crew can easily pull the sails down, and doing so doesn’t exert much energy.

Once the storms are finally over, you can begin making your way back to shore, hopefully without sustaining any damage to your boat.

If you’re caught in a particularly nasty storm, we would not advise you to lie ahull. You’re essentially a sitting duck when you do this, so conditions must be relatively safe. Otherwise, you’re much better off trying a few other tactics.

Or Use Your Storm Sails

For example, you can rely on your storm sails. If you’ve never used your storm sails before, here’s an introduction. The storm sail or jib attaches to an inner forestay, which is removable if necessary.

Some sailors use a flat-cut headsail as a storm sail and others a reefed roller genoa. The latter is generally not recommended. Since it’s not flat, the roller genoa can become baggy when the sail’s draft moves. This can also make your sailboat heel.

To lift your storm sail when needed, use a halyard. Your storm sail should be sheeted so it’s in a close-haul position. Jot down where the sail’s track is so you can determine pennant length at the stay base. When bad weather calls for you to use your storm sail, you can then connect your pennant to your stay base, hoisting your storm sail when you do.

The International Security Assistance Force or ISAF has published a set of rules known as the Offshore Special Regulations for Storm and Heavy Weather Sails. The rules encompass your sailboat’s storm sail, so keep these in mind when using the sail:

- Cut the luff by almost half (40 percent) when raising a reefed mainsail instead of a trysail.

- Measure the foretriangle to height squared. Then, ensure your staysail, also known as a heavy-weather jib, doesn’t exceed that height squared by more than 13.5 percent.

- You also need to know your forestay length, as the luff can’t be more than 65 percent of it.

- Calculate your foretriangle in height squared, then confirm your storm jib isn’t more than five percent of that.

- You must be able to sheet your trysail without the boom.

- The boom length by the luff length must be larger than the trysail, which needs an area less than 17.5 percent.

- You can’t rely solely on your luff groove when attaching the storm jib.

- You cannot use a high-tech fiber sail as your storm sail.

Or Even Heave-to

The third strategy we’d suggest when sailing in a storm is the heave-to. This is a means of stopping your boat, especially in conditions where the air is especially heavy and your sails could use a break.

If you’ve never done a heave-to before, first, you want to trim your jib so it’s facing the opposite (and yes, the wrong) side it usually does. Next, you want to trim your main, doing so hard. By lashing your helm after that, your sailboat has steerageway. This is just the least amount of speed needed for your helm to work.

Your sailboat, which moves up to get steerageway, will also go forward. This happens because your jib attempts to put downward pressure on the bow. Your bow then moves away from the wind, allowing the main to fill and propel your sailboat.

As you move, your lashed helm should move you in the direction of the wind. Your main sail will also soften. That’s when the jib goes into action, moving the bow as it had tried before. Your main sail fills back up so the rudder moves the bow towards the wind.

Your boat should be far enough from the wind, at least 60 degrees, that your speed is reduced to no more than 2 knots. Your sailboat also becomes more stable, especially compared to lying ahull.

You may have issues with the heave-to depending on which sails are up and how blustery the winds are on that particular day. You might need a sea anchor, attached near the bow, to keep your boat mostly still for the heave-to.

Never Sail Without Knowing the Weather

Using the advice and information in this article, you were able to navigate your sailboat safely back to shore in stormy conditions. You and your crew all admit it was quite an experience, and not one you’d like to repeat again anytime soon.

You don’t necessarily have to. Long before you ever have to look at the clouds and the birds around you to determine whether it will storm, you can use a weather app or website. We would recommend you make this a habit on the days you plan to set sail.

It’s not enough to check the forecast earlier in the week and then head out on the weekend. Weather forecasts change all the time, and you must be prepared. Look at the forecast at the beginning of the week, sure, but then also two days before you go out.

The night before your sailing trip, check the forecast again. Look hour by hour to see what kind of weather is predicted in your area. If your weather service offers a radar, use this too, as it shows when storms may roll in and when they would be their worst.

If inclement weather is on the forecast, we’d strongly dissuade you from sailing. Yes, there’s always a chance the forecast might be incorrect, but is it really worth chancing it? All it takes is surviving one scary experience at sea in a storm to say no, it isn’t.

Conclusion

Is a storm a-brewing while you’re out on the sea in your sailboat? The best way to avoid a storm is to never go out in inclement weather at all. If it’s already too late for that, then you can try a variety of tactics to get through the storm, such as the heave-to, lying ahull, or raising your storm sails. In some cases, you can sail back to shore or into open ocean to dodge the storm altogether.

The most important element of storm survival on your sailboat is the full understanding, communication, and cooperation among you and your fellow crew members. Stay safe!

I am the owner of sailoradvice. I live in Birmingham, UK and love to sail with my wife and three boys throughout the year.

Recent Posts

How To Sail From The Great Lakes To The Ocean

It’s a feat in and of itself to sail to the Great Lakes. Now you want to take it one step further and reach the ocean, notably, the Atlantic Ocean. How do you chart a sailing course to get to the...

Can You Sail from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico by Boat?

You have years of boating experience and consider yourself quite an accomplished sailor. Lately, you’ve been interested in challenging yourself and traveling greater distances than ever before. If...

How to Survive Sailing in a Storm: Tips and Tricks for a Safe Voyage

The thrill of sailing on calm waters is an experience like no other, but sometimes, Mother Nature has other plans. As a sailor, it’s crucial to be prepared for the unexpected, including sailing through a storm.

The phrase “sail through the storm” may sound counterintuitive, but it refers to the actions you need to take to safely navigate stormy weather while aboard a sailing vessel.

In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore what to do when sailing in a storm, how ships survive these tempestuous conditions, and the steps you can take to ensure your safety.

Key Takeaways Sailing in a storm is not something to take lightly. It requires careful planning, preparation, and execution. The best way to avoid sailing in a storm is to check the weather forecast regularly and plan your route accordingly. If possible, seek shelter before the storm hits or sail away from its path. If you have to sail through a storm, you need to reduce your sail area, balance your boat, steer actively, and secure everything on deck and below. There are different storm tactics that you can use depending on the wind direction, wave height, sea room, and boat type. Some of the most common ones are sailing under storm sails, running before the storm with a drogue, heaving-to, lying ahull, or anchoring. No matter what tactic you choose, you need to monitor the situation closely and be ready to adapt if necessary. You also need to take care of yourself and your crew by staying hydrated, rested, warm, and calm.

What is a Storm?

Before we dive into the details of sailing in a storm, let’s first define what we mean by a storm.

At this level, the sea is completely covered with long white patches of foam, and visibility is greatly reduced.

Of course, not all storms are created equal. Some storms are more severe than others, depending on factors such as wind direction, wind duration, air pressure, temperature, humidity, cloud cover, precipitation, lightning, thunder, etc.

Some storms are also more localized than others, meaning they affect only a small area for a short time. For example, squalls are sudden bursts of strong wind that usually last for less than an hour and can occur in clear or cloudy weather.

The most dangerous storms for sailors are tropical cyclones (also known as hurricanes or typhoons), which are large rotating systems of clouds and thunderstorms that form over warm ocean waters.

These storms can have wind speeds of over 74 knots (85 mph) and can cause massive waves, storm surges, flooding, landslides, and damage to coastal areas.

Tropical cyclones are classified into five categories based on their maximum sustained wind speed:

Tropical cyclones usually form between June and November in the Atlantic Ocean and between May and November in the Pacific Ocean.

They have different names depending on where they occur:

The best way to avoid sailing in a tropical cyclone is to stay away from its path. You can track the location and movement of tropical cyclones using satellite images, radio broadcasts, websites, apps, or other sources of information.

You can also use tools such as the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale or the Dvorak Technique to estimate the intensity of a tropical cyclone based on its appearance.

How to Prepare for Sailing in a Storm

The best way to deal with sailing in a storm is to prevent it from happening in the first place. This means planning your trip carefully and checking the weather forecast regularly before and during your voyage. You should also have a contingency plan in case things go wrong.

Here are some steps you can take to prepare for sailing in a storm:

Check the Weather Forecast

The weather forecast is your best friend when it comes to sailing safely. You should always check the weather forecast before you leave port and update it frequently while you are at sea. You should also pay attention to any weather warnings or alerts that may indicate an approaching storm.

There are many sources of weather information that you can use depending on your location and equipment. Some of them are:

- VHF radio: You can listen to marine weather broadcasts from local stations or coast guard services that provide information on wind speed and direction, wave height and period, sea state, visibility, precipitation, cloud cover, air pressure, temperature, and humidity. You can also request specific weather information from some stations or services using voice or digital selective calling (DSC).

- HF radio: You can receive weather fax images or text messages from various stations around the world that transmit information on synoptic charts, satellite images, wind/wave analysis, tropical cyclone warnings, etc. You need an HF radio receiver and a modem or software to decode the signals.

- NAVTEX: You can receive text messages from coastal stations that broadcast information on navigational warnings, meteorological warnings, ice reports, search and rescue information, etc. You need a NAVTEX receiver or an HF radio receiver with NAVTEX capability to receive the messages.

- NOAA National Weather Service

- NOAA National Hurricane Center

- PredictWind

- Buoyweather

- PassageWeather

- WeatherTrack

- Barometer: You can measure the air pressure using a barometer or an electronic device that has a barometer function. You can use the barometer readings to detect changes in the weather conditions. A falling barometer indicates an approaching low-pressure system that may bring bad weather. A rising barometer indicates an approaching high-pressure system that may bring good weather.

When checking the weather forecast, you should look for signs of an impending storm such as:

- A rapid drop in air pressure

- A sudden increase in wind speed or direction

- A change in cloud type or cover

- A change in temperature or humidity

- A change in visibility or precipitation

- A presence of lightning or thunder

- The presence of waterspouts or funnel clouds

You should also compare different sources of weather information to get a more accurate picture of the situation. Sometimes different sources may have conflicting or outdated information due to errors or delays in transmission or reception.

Plan Your Route

Once you have checked the weather forecast, you should plan your route accordingly. You should avoid sailing into areas where storms are likely to occur or where they may trap you against land or other obstacles. You should also have alternative destinations or safe havens in case you need to change your plans or seek shelter.

There are different tools and methods that you can use to plan your route, such as:

- Paper charts: You can use paper charts to plot your course and waypoints using a pencil, ruler, compass, and dividers. You should also have a chart table or a flat surface where you can spread out your charts and keep them dry and secure. Paper charts are reliable and easy to use, but they can be bulky, expensive, and outdated.

- Electronic charts: You can use electronic charts on your laptop, tablet, smartphone, or dedicated chart plotter device. You can also download or update your charts online or offline. Electronic charts are convenient and interactive, but they can be inaccurate, incompatible, or corrupted. They also depend on electricity and GPS signals, which may fail in a storm.

- Online tools: You can use online tools such as OpenSeaMap , SailingEurope , or FastSeas to plan your route using your web browser. You can also access various features such as weather data, nautical charts, marina information, etc. Online tools are useful and versatile, but they require an internet connection, which may not be available or reliable at sea.

When planning your route, you should consider factors such as:

- Distance: You should calculate the distance between your starting point and your destination, as well as between each waypoint along the way. You should also estimate the time it will take you to cover the distance based on your boat speed and the expected weather conditions. You should plan to sail at a comfortable and safe pace, without pushing yourself or your boat too hard.

- Direction: You should determine the direction of your course and waypoints using magnetic bearings or true bearings. You should also account for the variation and deviation of your compass due to the earth’s magnetic field and your boat’s magnetic interference. You should also adjust your course for the effects of wind, current, and leeway on your boat’s movement.

- Depth: You should check the depth of the water along your route using depth soundings or contour lines on your charts. You should also be aware of the tide levels and currents that may affect the depth of the water at different times and locations. You should avoid sailing in shallow water or near rocks, reefs, wrecks, or other hazards that may damage your boat or cause grounding.

- Destination: You should choose your destination carefully based on your preferences and needs. You should also research your destination before you arrive, such as its facilities, services, regulations, customs, culture, etc. You should also have a backup destination in case your primary one is unavailable or unsuitable.

Prepare Your Boat

Surviving a storm requires a great level of preparedness and it all begins long before setting out on a sail. As such, your chances of weathering a storm will increase if your boat is properly prepared to endure bad days on the water.

A major part of controlling your boat and the crew in a heavy storm is being prepared for the worst. This means that you should have your boat properly rigged to easily access anything in short order. Whether you can see a storm coming from far away or see it within seconds and on top of your head, the boat should be well prepared to deal with any condition.

It’s fundamental to ensure that your lifelines are secure, the lines are strong and unworn, and all the emergency gear is on board and up to date. You should also update yourself on the weather on the days you’re planning to go out though it may be inaccurate.

Some of the things you should check and prepare before sailing include:

- Hull integrity : Check for any cracks, leaks, or damage on the hull that could compromise its strength or water tightness. Repair any defects or reinforce any weak spots as needed.

- Rigging : Check all the standing rigging (mast, shrouds, stays) and running rigging (halyards, sheets) for any signs of wear or damage. Replace any frayed or broken lines or fittings. Lubricate any moving parts such as blocks or winches. Make sure all the lines are neatly coiled and secured to prevent tangling or tripping.

- Sails : Check all your sails for any tears or holes that could worsen in high winds. Repair any damage or replace any worn-out sails as needed. Make sure you have at least one set of storm sails (storm jib and trysail) on board that are easy to hoist and lower. Reefing lines should be ready to use at any time.

- Engine : Check your engine for any issues that could affect its performance or reliability. Change the oil and filter if needed. Check the fuel level and quality. Make sure you have enough spare fuel on board. Test the engine before leaving the dock to make sure it starts and runs smoothly.

- Batteries : Check your batteries for any corrosion or damage that could affect their capacity or charge. Make sure they are fully charged before leaving the dock. Test all your electrical systems (lights, instruments, radios) to make sure they work properly.

- Bilge pumps : Check your bilge pumps for any clogs or malfunctions that could prevent them from working effectively. Make sure they are wired correctly and have enough power supply. Test them before leaving the dock to make sure they pump water out of the bilge.

- Emergency gear : Check all your emergency gear for any damage or expiration dates that could affect their usefulness or safety. Make sure you have enough life jackets, harnesses, tethers, liferaft, EPIRB, VHF radio, distress flares, fire extinguishers, first aid kit, etc. on board, and that they are easily accessible and visible. Make sure everyone knows how to use them properly.

Prepare Yourself

Your boat is not the only thing that needs to be prepared for sailing in a storm. You also need to prepare yourself mentally and physically for the challenge. You need to be aware of the risks and consequences of sailing in a storm and be ready to face them. You also need to take care of your health and well-being during the storm.

Here are some steps you can take to prepare yourself for sailing in a storm:

You need to learn as much as you can about sailing in a storm before you encounter one. You need to read books, articles, blogs, forums, etc. that provide information, advice, tips, tricks, stories, etc. about sailing in a storm.

You also need to watch videos, podcasts, webinars, etc. that show demonstrations, explanations, interviews, testimonials, etc. about sailing in a storm.

You also need to take courses, workshops, seminars, etc. that teach skills, techniques, strategies, etc. about sailing in a storm. Some examples of learning resources are:

- Storm Tactics Handbook by Lin and Larry Pardey

- Sailing in Storms by Sailing La Vagabonde

- Podcast by The Boat Galley

- Heavy Weather Sailing Course by NauticEd

You need to practice your skills and techniques for sailing in a storm before you face one. You need to practice sailing in different wind and wave conditions and try different storm tactics.

You also need to practice using your gear and equipment and test their functionality and reliability. You also need to practice communicating with your crew and other boats or shore stations and test their availability and clarity.

The best way to practice sailing in a storm is to sail in moderate weather conditions that simulate some aspects of a storm, such as strong winds, choppy waves, low visibility, etc.

You should avoid sailing in extreme weather conditions that may endanger your safety or damage your boat. You should also avoid sailing alone or without proper supervision or assistance.

When practicing sailing in a storm, you should follow these steps:

- Choose a suitable location that has enough sea room and no obstacles or hazards.

- Check the weather forecast and choose a time that has favorable conditions for practicing.

- Inform someone on shore about your plan and expected return time.

- Prepare your boat and yourself as if you were sailing in a real storm.

- Sail out of the harbor and head into the wind and waves.

- Try different storm tactics such as reefing, heaving-to, running with a drogue, etc.

- Use your gear and equipment such as storm sails, life jackets, VHF radio, etc.

- Communicate with your crew and other boats or shore stations using voice or signals.

- Monitor the situation closely and be ready to adapt if necessary.

- Sail back to the harbor when you are done practicing or when the conditions change.

You need to rest well before sailing in a storm because you may not get much sleep during the storm. You need to sleep at least eight hours before leaving port and take naps whenever possible while at sea.

You also need to avoid alcohol, caffeine, or drugs that may affect your sleep quality or alertness.

Sleeping well before sailing in a storm will help you:

- Reduce fatigue and stress and improve mood and motivation

- Enhance memory and learning and improve decision-making and problem-solving

- Boost immunity and healing and prevent illness and injury

You need to eat well before sailing in a storm because you may not have much appetite during the storm. You need to eat balanced meals that provide enough calories and nutrients to sustain your energy and health.

You also need to avoid spicy or greasy foods that may cause indigestion or nausea.

Eating well before sailing in a storm will help you:

- Maintain blood sugar and blood pressure levels and prevent hypoglycemia or hypertension

- Support muscle and bone strength and prevent weakness or injury

You need to hydrate well before sailing in a storm because you may lose a lot of fluids through sweating, vomiting, or diarrhea during the storm. You need to drink plenty of water or electrolyte drinks that can replenish your hydration and electrolyte levels.

You also need to avoid alcohol, caffeine, or carbonated drinks that may dehydrate you or upset your stomach.

Hydrating well before sailing in a storm will help you:

- Prevent dehydration and heatstroke and improve thermoregulation and cooling

- Maintain blood volume and circulation and prevent hypotension or shock

- Support kidney and liver function and prevent infection or toxicity

How to Sail Through a Storm

If you have done everything you can to prepare for sailing in a storm, but you still find yourself in one, don’t panic. You need to stay calm and focused and follow some basic principles and procedures to sail safely through the storm.

Here are some steps you can take to sail through a storm:

Reduce Sail Area

The first thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to reduce your sail area. This will reduce the wind pressure on your boat and make it easier to control and balance.

You need to reef your sails as soon as possible, before the wind gets too strong and makes it difficult or dangerous to do so. You also need to furl or stow any unnecessary sails, such as spinnakers, genoas, or staysails.

The amount of sail area you need to reduce depends on the wind speed, the wave height, the boat type, and your comfort level.

As a general rule, you should reef your sails when the wind speed reaches 15 knots (17 mph) and reduce them further for every 5 knots (6 mph) increase.

You should also reef your sails when the wave height reaches 1 meter (3 feet) and reduce them further for every 0.5 meters (1.5 feet) increase.

You should always reef your mainsail first, then your headsail. This will keep your boat balanced and prevent weather helm (when the boat wants to turn into the wind) or lee helm (when the boat wants to turn away from the wind). You should also reef your sails evenly and symmetrically, without leaving any loose or flapping parts.

If you have storm sails on board, you should hoist them when the wind speed reaches 40 knots (46 mph) or more. You should lower your regular sails completely and secure them on deck or below.

You should hoist your storm jib just forward of the mast and your storm trysail on a separate track on the mast or on the boom.

Balance Your Boat

The second thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to balance your boat. This will reduce the heel angle and rolling motion of your boat and make it more stable and comfortable.

You need to adjust your sail trim, your weight distribution, and your ballast system (if you have one) to achieve a balanced boat.

The sail trim is how you set the angle and shape of your sails relative to the wind direction and strength. You need to trim your sails so that they are not too tight or too loose, but just right.

You also need to trim your sails so that they are not too full or too flat, but just right. A well-trimmed sail will have a smooth and even curve along its luff (front edge) and leech (back edge), without any wrinkles or creases.

The weight distribution is how you arrange the weight of your crew and gear on board. You need to distribute your weight so that it is not too far forward or too far aft, but just right.

You also need to distribute your weight so that it is not too far to windward or too far to leeward, but just right. A well-distributed weight will keep your boat level and centered, without any pitching (up-and-down motion) or yawing (side-to-side motion).

The ballast system is how you use water tanks or movable weights to adjust the stability of your boat. You need to use your ballast system so that it is not too full or too empty, but just right.

You also need to use your ballast system so that it is not too far forward or too far aft, but just right.

A well-used ballast system will increase the righting moment (the force that keeps your boat upright) and decrease the capsizing moment (the force that tips your boat over).

Steer Actively

The third thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to steer actively. This will help you avoid being hit by breaking waves or being pushed off course by gusts of wind.

You need to steer your boat so that it is not too close or too far from the wind direction, but just right. You also need to steer your boat so that it is not too fast or too slow, but just right.

The best way to steer actively is to use a combination of visual cues and instruments. You need to look at the wind indicator (such as a Windex ) on top of your mast or on your sail to see where the wind is coming from.

You also need to look at the waves around you to see where they are going and how big they are. You also need to look at the compass on your dashboard or on your wrist to see what direction you are heading.

You also need to listen to the sound of the wind in your ears and feel its pressure on your face and body. You also need to listen to the sound of the water against your hull and feel its movement under your feet and seat.

You also need to listen to the sound of your sails flapping or luffing and feel their tension on your hands.

You also need to use instruments such as GPS, AIS, radar, autopilot, etc. to see where you are, where other boats are, where obstacles are, etc.

You also need to use instruments such as a speedometer, tachometer, anemometer, etc. to see how fast you are going, how fast your engine is running, how fast the wind is blowing, etc.

You should steer actively using small and smooth movements of the helm or tiller to keep your boat on course and speed.

You should avoid steering aggressively using large or jerky movements of the helm or tiller that may cause your boat to lose control or speed.

Choose Your Storm Tactic

The fourth thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to choose your storm tactic. This will help you cope with the wind and wave conditions and reduce the risk of damage or injury.

You need to choose a storm tactic that suits your boat type, your crew’s ability, and your situation. You also need to have the right equipment and skills to execute your storm tactic.

There are different storm tactics that you can use, such as:

Forereaching

This is when you sail close-hauled with reduced sail area and maintain a slow but steady speed into the wind and waves. This tactic is good for short-duration storms or when you need to stay close to your position. It is also good for boats that have good upwind performance and can handle steep waves. The advantages of this tactic are:

- It keeps the boat stable and balanced

- It reduces the impact of breaking waves

- It allows you to change course or tack if needed

The disadvantages of this tactic are:

- It can be tiring and uncomfortable for the crew

- It can cause excessive leeway and drift

- It can expose the boat to wind shifts or gusts

Running off

This is when you sail downwind with reduced sail area and let the wind and waves push you away from the storm center. This tactic is good for long-duration storms or when you have enough sea room to run. It is also good for boats that have good downwind performance and can handle following seas. The advantages of this tactic are:

- It keeps the boat fast and agile

- It reduces the apparent wind speed and noise

- It allows you to outrun the storm or reach a safe haven

- It can be risky and challenging for the crew

- It can cause broaching or surfing

- It can expose the boat to breaking waves or rogue waves

This is when you stop the boat by setting the sails and rudder in opposite directions and creating a slick of turbulent water that acts as a brake. This tactic is good for extreme storms or when you need to rest or wait. It is also good for boats that have a balanced sail plan and a deep keel. The advantages of this tactic are:

- It keeps the boat calm and steady

- It reduces the stress and fatigue of the crew

- It allows you to conserve fuel and water

- It can be difficult and dangerous to set up or resume sailing

- It can cause drifting or leeway

Lying ahull

This is when you drop all sails and let the boat drift freely with no steerage. This tactic is good for last-resort situations or when you have no other option. It is also good for boats that have a strong hull and a low profile. The advantages of this tactic are:

- It keeps the boat simple and passive

- It requires no effort or skill from the crew

- It allows you to abandon ship if needed

- It keeps the boat vulnerable and unpredictable

- It increases the risk of damage or injury

- It offers no control or direction

Survive the Storm

The fifth and final thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to survive the storm. This means that you need to do whatever it takes to keep yourself, your crew, and your boat alive and intact until the storm passes. You need to monitor the situation constantly and be ready to adapt or change your plan if necessary. You also need to communicate with your crew and other boats or shore stations and seek help if needed.

Here are some tips to help you survive the storm:

Stay calm and positive

The most important thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to stay calm and positive. Panic and despair will only make things worse and cloud your judgment.

You need to trust your boat, your crew, and yourself and believe that you can make it through the storm. You also need to encourage and support your crew and keep their morale high.

You can use humor, music, games, or stories to lighten the mood and distract from the stress.

Stay alert and aware

The second most important thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to stay alert and aware. Complacency and negligence will only increase the danger and reduce your chances of survival.

You need to watch the wind, the waves, the clouds, and the horizon for any signs of change or improvement. You also need to check your boat, your gear, your instruments, and your crew for any signs of damage or injury.

You also need to listen to weather updates, distress calls, or safety messages on your radio or phone.

Stay safe and secure

The third most important thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to stay safe and secure. Injury and damage will only worsen the situation and compromise your recovery.

You need to wear your life jacket, your harness, and your helmet at all times and clip yourself to a strong point on the boat. You also need to secure all loose items on deck or below and close all hatches and ports.

You also need to avoid going overboard, getting hit by flying objects, or falling down.

Stay warm and dry

The fourth most important thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to stay warm and dry. Hypothermia and dehydration will only weaken your body and mind and impair your performance.

You need to wear waterproof and breathable clothing that can protect you from the wind, rain, spray, and cold. You also need to drink plenty of water or electrolyte drinks that can replenish your hydration and electrolyte levels.

Stay fed and rested

The fifth most important thing you need to do when sailing in a storm is to stay fed and rested. Hunger and fatigue will only lower your energy and health and affect your decision-making and problem-solving.

You need to eat balanced meals that provide enough calories and nutrients to sustain your energy and health. You also need to sleep at least eight hours before leaving port and take naps whenever possible while at sea.

Frequently Asked Questions

Here are some of the most frequently asked questions about sailing in a storm:

To sail through the storm means to overcome a difficult or challenging situation with courage and resilience. It can also mean enduring or surviving a storm at sea.

Ships survive storms by following some of the same principles as sailboats: reducing speed, balancing weight, steering into or away from the wind and waves, using stabilizers or ballast tanks, and seeking shelter or open water as needed.

Yes, you should lower sails in a storm, or at least reduce sail area by reefing or switching to storm sails. This will help you control your boat better and prevent damage from high winds.

Sailing ships do different things in a storm depending on their size, type, design, crew, equipment, and situation. Some of the common things they do are: reefing sails, switching to storm sails, running before the storm, heaving-to, lying ahull, forereaching, etc.

You steer a ship in a storm by using your rudder and sails (or engine) to adjust your course and speed according to the wind and wave direction. You should try to avoid sailing on a reach across tall breaking waves, as they can roll your ship over. You should also try to sail away from the storm’s path, especially its dangerous semicircle.

Sailing in a storm is one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences that a sailor can have. It requires a lot of preparation and skill to sail safely through a storm and survive its fury. It also requires a lot of courage and resilience to face the storm and overcome its fear.

By following the steps outlined in this article, you can increase your chances of sailing in a storm successfully and enjoy its thrill. You can also learn valuable lessons and gain confidence from sailing in a storm that will make you a better sailor.

Remember, the best way to deal with a storm is to avoid it if possible, prepare for it if inevitable, and survive it if necessary.

Happy sailing! ⛵️🌊⚡️🌬️🌈